Last of the Vegas

Loved by Amelia Earhart and Wiley Post, these Lockheed beauties are museum pieces today—all but one.

:focal(2164x2207:2165x2208)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f1/e9/f1e968db-7314-4f49-8ceb-dea1657eb084/34f_on2014_rv43824vandermeulen_live.jpg)

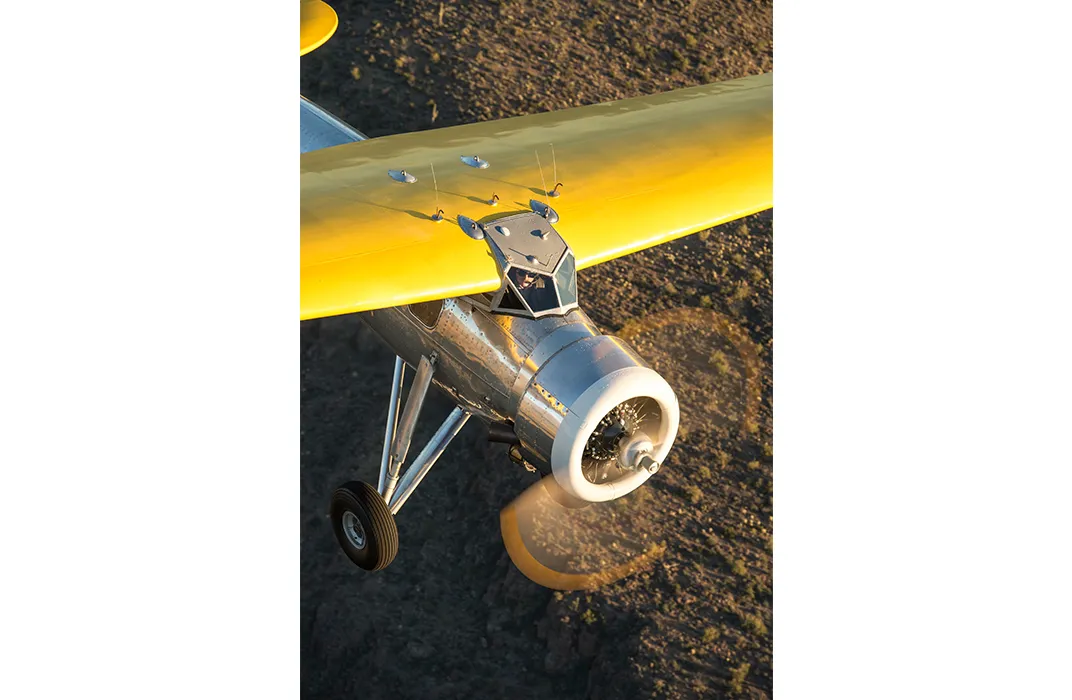

Lockheed's engineering genius didn’t start with Kelly Johnson, says John Magoffin, standing by his Lockheed Vega last July at the Experimental Aircraft Association annual fly-in. The genius who designed Magoffin’s airplane began his career at Lockheed in 1916 and later built a reputation as familiar to aviation fans as Johnson’s. The Vega’s chief engineer was Jack Northrop, and he was assisted by another aviation notable: Jerry Vultee, who later founded a company that merged with Consolidated Aircraft to form Convair.

What the two created was “a revolution in the sky,” says Magoffin, quoting the title of a book about Lockheed’s early single-engine airplanes. He never takes his eyes off the sparkling aluminum airplane next to him, as he talks to a succession of enthusiasts at the Experimental Aircraft Association’s fly-in at Oskhosh, Wisconsin, who all want to get a closer look at the only flying Vega in the world.

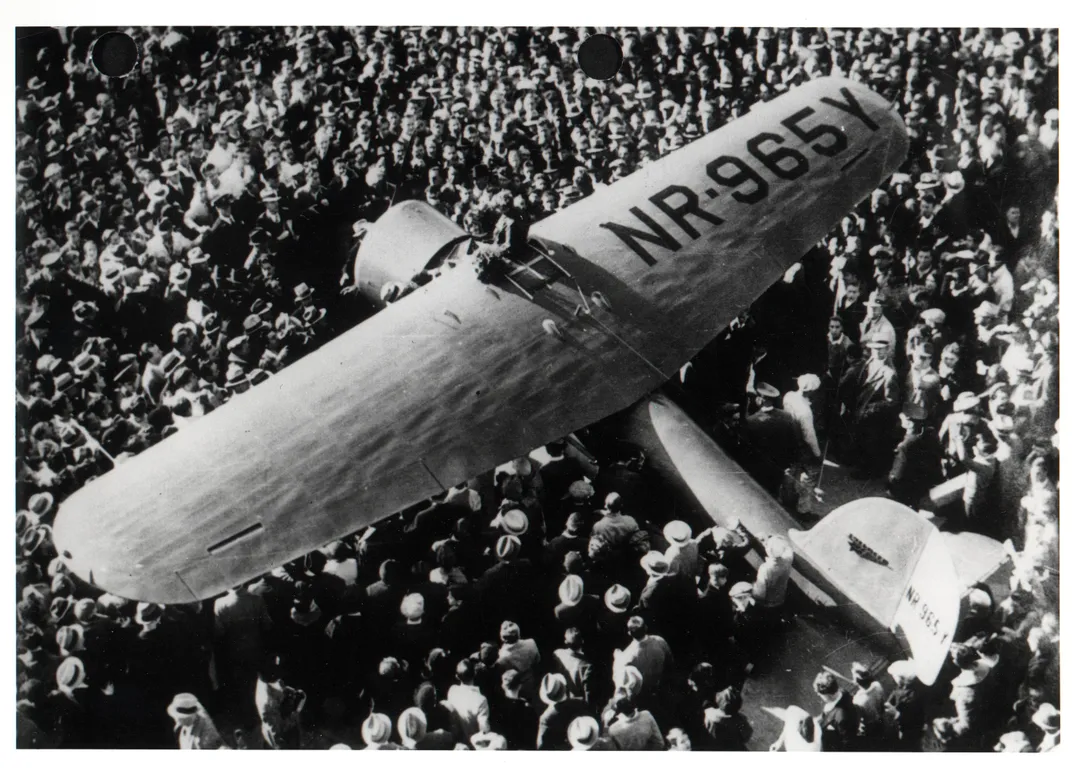

The Vega was powerful and sleek, unlike most of the other airplanes flying in 1927—“an artillery shell amid a gaggle of box kites,” wrote aviation author Budd Davisson in a recent issue of Sport Aviation. Propelled by a 450-horsepower Pratt & Whitney Wasp Junior, the Vega was capable of flying more than seven hours at speeds up to 168 mph and altitudes up to 18,000 feet. It quickly gained a following among racers and record-breakers. Amelia Earhart flew hers on the second solo flight across the Atlantic in 1932. Wiley Post flew his around the world the year after. Both Vegas now reside in the National Air and Space Museum. Several heavily modified Vegas shattered performance records once during an attempt to set a cross-country speed record. (The attempt was made by Captain Ira Eaker, who later commanded the U.S. Eighth Air Force in Europe during World War II. Part way through the flight, Eaker was forced to land because of air in the fuel lines.) Explorers bought Vegas to haul supplies to inhospitable places like Antarctica; airlines used them as workhorses.

Magoffin’s Vega is a DL-1B, one of 10 built in Detroit with a metal fuselage over its wooden frame. Its immediate predecessors off the line were flown by the U.S. Army Air Corps as executive transports, and Magoffin painted his to mimic one that flew for the 35th Pursuit Squadron, based at Langley Field, Virginia in 1932. “It was used as an executive/VIP transport, but believe it or not, it was faster than the top-of-the-line fighters the U.S. military had at that time,” says Magoffin.

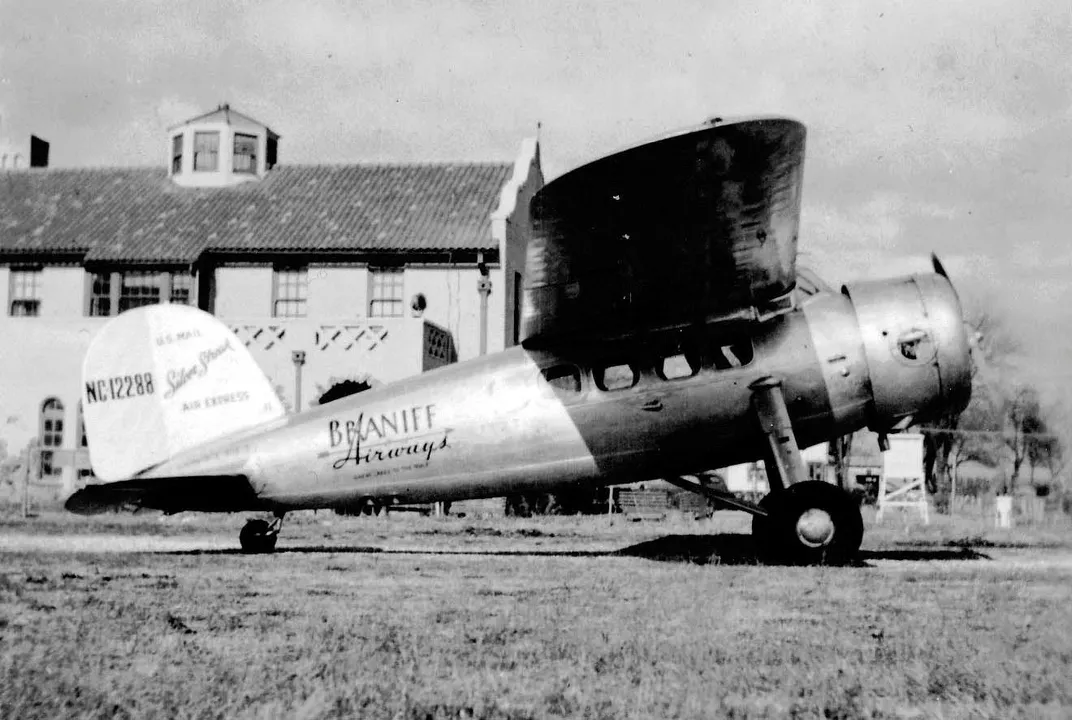

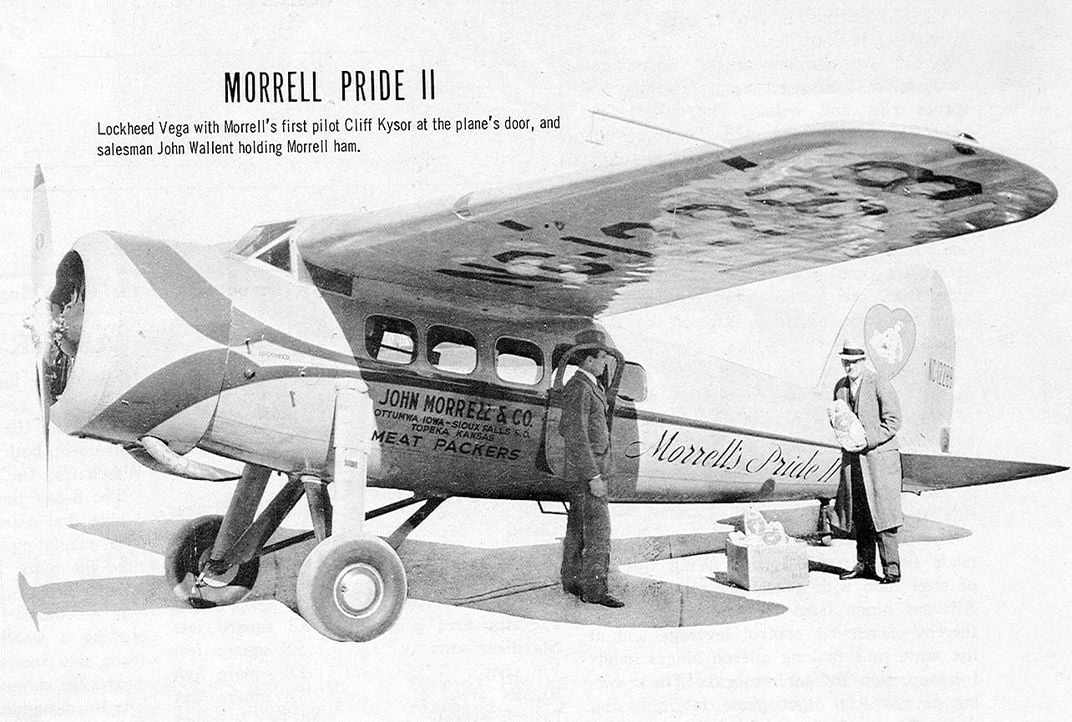

Magoffin’s airplane was purchased in 1933 by the Morrell Meat Packing Company of Ottumwa, Iowa, which made it the first executive aircraft in the country. Later it was flown by a series of owners, including Braniff Airlines. In 1942, it was acquired by the Green Construction Company of Iowa, which flew the airplane to Alaska to deliver cargo like dynamite and blasting caps for building the Alaska-Canada Highway.

Alaska is where Magoffin first heard about it. In 1977, right out of college and with a fresh commercial pilot’s ticket in his hands, he headed to Galena to become a bush pilot. Alaska is a refuge for all types of old airplanes, and Magoffin flew just about all of them, from the ultra-rare Fairchild Pilgrim to the ubiquitous Piper Cub to the world’s heaviest tail-dragger, a World War II-era Curtiss C-46 Commando that still flies today. He’s restored a Lockheed Electra and two Lodestars, but it’s clear that his heart belongs to the Vega.

Magoffin points out that the airplane’s forward fuselage forms a circle with a diameter just large enough to accommodate the most powerful engine of the day, the Wright Whirlwind (quickly replaced by the Pratt & Whitney Wasp). The circle softens to a symmetrical ellipse just aft of the engine firewall, then the shape tapers to another circle where the rear fuselage joins the empennage. The Vega is one of the first airplanes with a balance tab on the aileron and a horizontal stabilizer that was also trimmable, both innovations that have since become standard for nearly all airplanes. They also helped make the airplane fast.

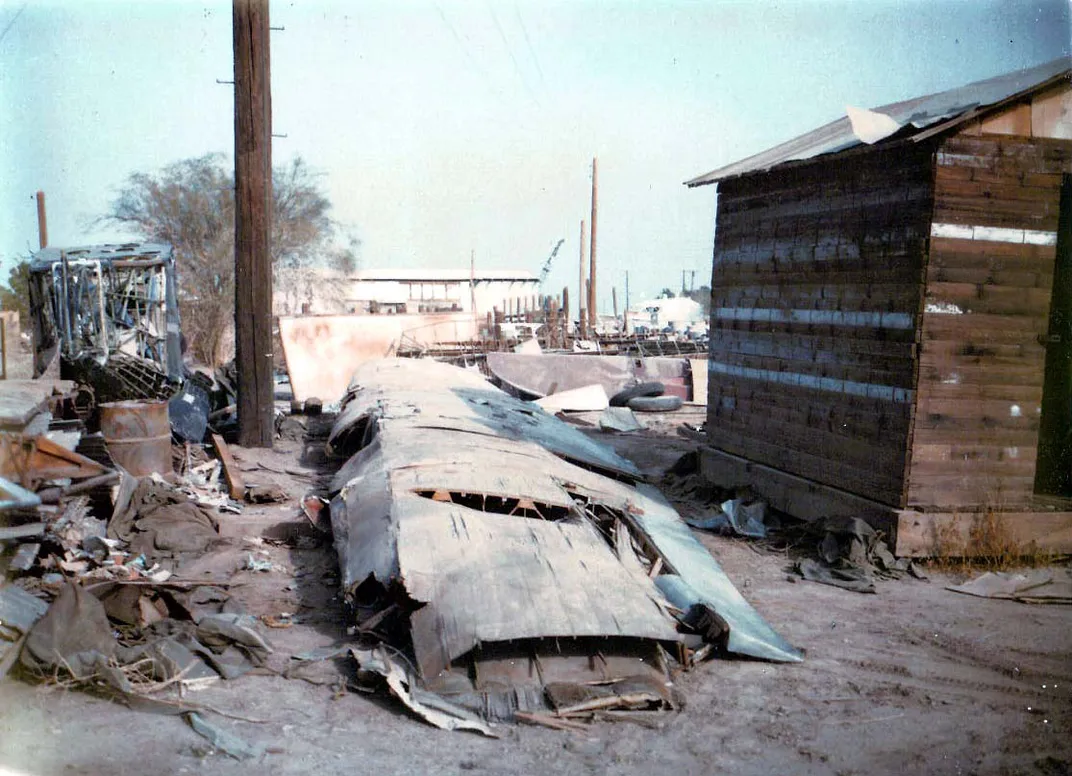

The airplane had been abandoned after a landing accident in Ruby. By the time Magoffin flew in to check it out, the airplane had been shipped to California, then eventually to Ottumwa, Iowa, where it was restored to flight status in 1969. In Ruby, “they said ‘You’re ten years too late, son,’ ” says Magoffin. The restorer was Robert Taylor, president of the Antique Aircraft Association, who stored the airplane in his hangar for years after it was damaged in a crash. Thomas and Magoffin are the only two living pilots known to have flown the Vega.

In 1995, Magoffin saw an advertisement in an industry magazine for a partially restored Vega; it turned out to be the same one he’d sought in Alaska. He called the owner and said, “I’m on my way with a check.” After buying it, he brought it to Rick Barter’s restoration shop in Marana, Arizona, where the Vega received a new wooden tail. The wings and control surfaces were restored using doped fabric on mahogany plywood, supported by mahogany stringers and a 42-foot Douglass fir main spar.

The fuselage was straightened and many mechanical components were built from scratch, including the complex engine firewall with cut-out recesses for the rudder pedals. Whenever possible, Barter tried to preserve the airplane’s original equipment, including its individual quirks: During its sojourn in Alaska, the original Wasp Junior engine had been replaced with a lighter R1340 Wasp and a Vultee BT-13 engine cowl, which Barter and Magoffin elected to keep.

The most difficult part of the restoration was the horizontal stabilizer, says Barter. “That took me three months to build. The horizontal trim system was a bit tricky to get working right. It’s a drive shaft with a crank in it and a gear in the cockpit, a lot of universal joints....

“The tail rides on pinion gears and two rack gears that are curved—it’s an interesting setup,” Barter adds. “I’ve never seen it on an older airplane like that.”

“If you look at the old photos of the Lockheed factory, you’ll see they have the most basic of hand and shop tools there,” says Magoffin. “So anything associated with the aircraft can be manufactured with basic shop tools. I did have to replace some of the castings, and instead of making the castings, I had them machined out of certificated billet material, which far surpasses the original strength.”

The Vega maintains its original registration from 1933: NC12288. It was never re-registered, and flies under the same federal certifications from that era.

Magoffin keeps the Vega in pristine flying condition and makes regular appearances with it at airshows: At Oshkosh it garnered several awards and emblazonment on a T-shirt. His next step, he says, is to add an interior with seats like those a passenger in the 1930s would have seen. He has no doubt that his airplane is the finest in the world, and that any aviation aficionado would choose to fly the Vega over any other; when he’s not flying the Vega, Magoffin pilots an Airbus A320 for US Airways, making him probably the only person on the planet who flies a 21st century airliner in the morning and a 1930s airliner in the afternoon. But given the choice between the ultra-modern Airbus and his ancient Vega, Magoffin would take the Vega every time.