Legends of Vietnam: Super Tweet

Yeah. The A-37 was small. So was Napoleon.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/10S_DJ10-flash.jpg)

Looking for Mach-busting splendor in million-dollar wonders from the heavies of the U.S. military-industrial complex? This ain't it. The A-37 Dragonfly was a waist-high, subsonic light attack aircraft that could lift its own weight in fuel and armaments, built by a manufacturer known for civilian pleasure craft. You could get a half-dozen for the price of a single F-4. The A-37 brought jet-propelled combat in Vietnam down from rarefied heights to the low-and-slow—where the acrid haze of rice-burning season permeated the unpressurized cockpit and you plucked bullets from Viet Cong small arms out of the armor plate under your seat after a mission. Its claim to fame?

"I've checked around and there really isn't anyone here who can help you," wrote a spokesperson at Cessna-Textron Inc. after I requested background on the only jet fighter the company ever made. Even books on the air war in Vietnam give it only passing reference, and one official Air Force account leaves it out altogether. I know some guys who are saying "We told you so" right now.

I was with them in a Branson, Missouri hotel for the A-37 Association reunion in May. "Forget it," Robert Macaluso answered, when I asked about Dragonfly mystique. "If the airplane isn't fast and doesn't wow all the girls, then the airplane doesn't count. We didn't have clout. We never got credit." If "credit" means "promotions," he's right: A-37 pilots do not lead the league. The career arc of its pilots hit a glass ceiling that kept many from top ranks. Macaluso, a Distinguished Flying Cross recipient who went on to a career as a Continental Airlines captain, voices a recurrent theme among A-37 alumni: While Vietnam's "Heavy Metal"—the McDonnell F-4, North American F-100, and Republic F-105—deservedly got glory, the A-37 couldn't catch a break.

This wasn't your flying club's Cessna. The most recognized name in civil aviation launched its military line in 1949, with an observation aircraft, the O-1 Bird Dog, a high-winger that became famous for drawing enemy fire but not packing much to return it. In 1952, when the Air Force needed a trainer to transition fighter pilots into the Jet Age, Cessna entered a concept it called the Model 318 in the design competition—and won. Designated T-37 by the Air Force, the trainer featured two French-designed Turbomeca J69 engines and side-by-side seating for student and teacher, a show-and-tell environment superior to tandem cockpits. Straight "Hershey bar" wings, forgiving of novice inelegances, plus a wide-track, training-wheels landing gear, eased the segue from propellers. Most students soloed after only six hours. Besides, it just looked user-friendly. Other pilots scaled ladders to mount their exalted steeds. T-37 trainees threw a leg over and eased into the cockpit like they were getting into a top-down Corvette.

It sounded like nothing else, however. The 21,000-rpm turbine blades of the feverish J69s produced a high-pitched squeal, earning the nickname "Tweety Bird," soon shortened to "Tweet." There are ground crew alums walking around today with hearing loss in the upper frequency ranges from that earplug-penetrating shriek. Fated to serve with aircraft called Phantoms and Thunderchiefs, a tag like "Tweet" perhaps marked the beginnings of the airplane's stigma. (It got worse: Some called it Baby Jet; others, the "6,000-Pound Dog Whistle.")

Nevertheless, the T-37 ended up as the Air Force's primary jet trainer for 50 years. It remains the soft-focus, first romance for generations of pilots who advanced to everything from lunar landers to the F-22 Raptor.

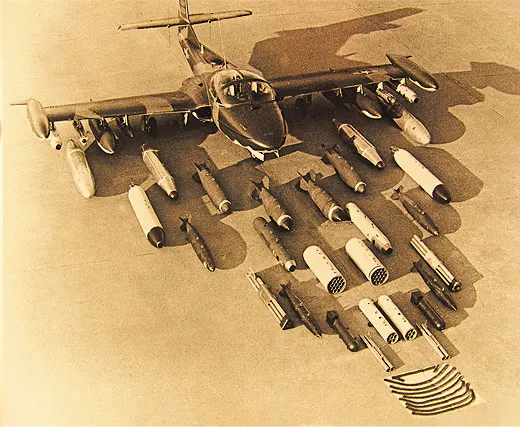

By 1966, the escalating war in Vietnam was decimating the Douglas A-1 Skyraider, a World War II-era attack aircraft. Younger jet-trained pilots had difficulty being re-educated for the radial engine taildragger. ("I took two rides and it scared the bejeezus out of me," Bob Macaluso said.) A few years earlier, the Air Force had evaluated a T-37 modification for light attack missions; in 1966, it decided to order the YAT-37D to supplant A-1s. General Electric J85 engines had replaced the Turbomecas, delivering twice the power yet squelching the ear-splitting squeal. Wingtip fuel tanks and ordnance-bearing pylons had been added, plus a 7.62-mm mini-gun in the nose. Staple arms were Mk.80 bombs, cluster tubes, and napalm tanks. Finally, a Cessna could fight back.

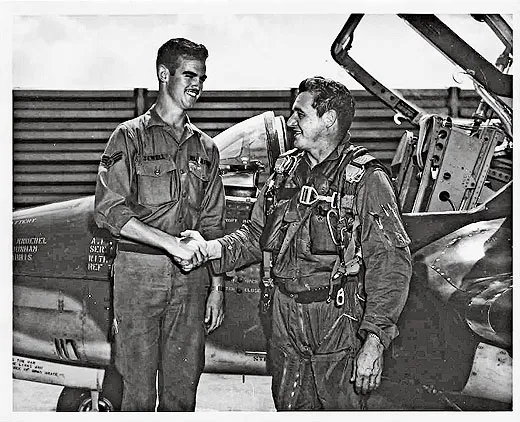

The YAT-37D became the prototype for the A-37A. Cessna converted 39 T-37s to A-37As and sent 25 to Vietnam for Operation Combat Dragon, overseen by Lieutenant Colonel Lou Weber, a red tape-averse veteran of the legendary World War II Flying Tigers. At England Air Force Base in Louisiana, Weber brainstormed a battle plan and assembled the unit that became the 604th Air Commando Squadron, based at Bien Hoa, South Vietnam.

Weber's plan was an Air Force first: To fast-track the A-37 into action, he proposed making live combat part of the aircraft's operational testing. "No other aircraft had ever gone into combat that hadn't been tested previously," said Lon Holtz, a Silver Star recipient who also flew F-4s and F-16s. "Other fighters were proven here in the States—they'd gone through their certification, their weapons loading, their maintenance procedures. That's not the case with the A-37. This aircraft went over to prove itself in combat."

The diminutive A-37s were crated, then transported to Vietnam in Lockheed C-141s. Cessna employees unboxed and assembled each one. This kitplane, "batteries included" debut didn't boost its cred among pilots of the brawny Super Sabres based at Bien Hoa. "We took a whole bunch of crap from them at the officers' club," Lon Holtz told me in Branson. The fighter got a moniker upgrade from "Tweet" to "Super Tweet." "And they called us Mattel Marauders too," he laughed.

Thirty pilots accompanied the airplanes, most having 25 hours or less in the T-37. They came from all types of aircraft, bombers to transports. Weber wanted to make sure that a pilot with any experience could fly the Super Tweet in combat. His theory and implementation were built on a no-frills formula: Make a rudimentary fighter out of a trainer that every pilot was already comfortable with and put it into action fast. No advanced weapons systems to learn—a low-tech, World War II-style bomb delivery. Traditional nine-month training program to get a guy into combat? Not required.

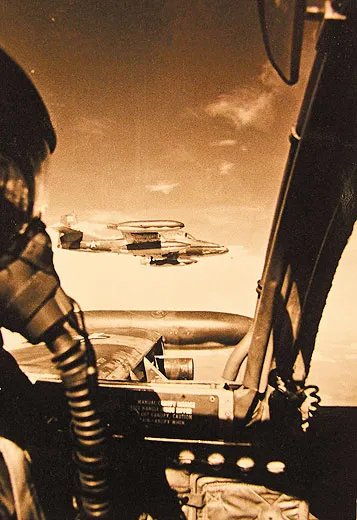

In August 1967, A-37s began providing close air support for two areas in South Vietnam, known as III and IV Corps. The straight-wing configuration enabled lower, 100-mph-slower engagement than swept-wing fighters. This translated to pinpoint bomb accuracy—averaging inside a 45-foot radius—and giddy forward air controllers. ("Thank God," one blurted over an open mike on one sortie when F-4s were replaced by A-37s; "now I have somebody who can actually hit the damn target.")

But wouldn't that tactic also make the aircraft clay pigeons for enemy gunners? "I climbed in the airplane, flew my first combat mission, got shot at, and immediately figured out they couldn't hit me," Holtz said. In a dive, a Dragonfly presented a measly target. Enemy gunners were confounded by its atypical speeds and altitudes, said A-37 Association founder Ollie Maier, a captain who flew more than 500 missions. "They were accustomed to leading a certain amount in their aim because the F-4s and F-100s came in high and fast," Maier said. "We'd come in and see their tracers way out in front. They often tended to over-lead us."

Low-level missions presented certain hazards, of course. "I was always cleaning out grass and tree limbs from underneath the A-37s," said Charlie Kraesig, a maintenance officer. "These guys would get target fixation because they were always coming in so low and concentrating on the target and they just didn't realize how close to the ground they were."

Bob Chappelear can verify that observation, especially the part about tree limbs. As an Air Force captain, barreling north in Cambodia, he saw too late a particularly tall tree in his path. "I sheared off the top 15 feet," he said. The 400 mph impact made his A-37 yaw radically. The entire leading edge of one wing was crushed. Napalm was spraying all over the airplane. "I told myself, if I'm still alive ten seconds from now, I'd better raise the ejection handles and squeeze the triggers," Chappelear said. "But then I thought, I'm not very far from a bunch of guys I just bombed, so that might not be a smart idea." The A-37 strained away from highway-dusting height with its left wing bent back 25 degrees and drop tanks dangling. Both GE jet engines faithfully delivered thrust as Chappelear ran a controllability check. "Everything was fine," he said, still sounding grateful nearly 40 years later. "It was like ‘Fly it home and land it.' Besides, it was getting dark and I did not want to spend the night in that jungle."

In Vietnam, the air war began when gear left ground—sometimes before. "A lot of times Charlie was sitting right off the end of our own runway shooting at us as we took off," Maier said. This made pilots grateful for the Dragonfly's pole-vaulting climbout rate. While a fully loaded F-100 might use every yard of pavement just getting airborne, "we were already leveling off up at 1,000 feet before we even got to the end of the runway," said Maier. At sprawling Bien Hoa, snipers occasionally infiltrated even the grassy infield. Lloyd Langston, a first-wave Combat Dragon pilot, told me of traversing the long, exposed taxiways with an M-16 rifle across his lap.

It might have been handy aloft too. The nose-mounted mini-gun—"Basically, a BB pistol in combat," Lon Holtz called it—was of limited effectiveness penetrating heavy jungle canopy when strafing. "In 350 missions, I think I used it once," he said.

In its first 3,000 sorties, not one A-37A was downed by enemy fire. Combat Dragon continued until December 1967. After five months and 19,000 ordnance deliveries, the airplane and Weber's operational strategy were vindicated. From studying the 5,000 combination flight tests–combat missions flown during the operation, Cessna developed the bulked-up A-37B, with more thrust from newer-generation J85 engines plus inflight refueling capability.

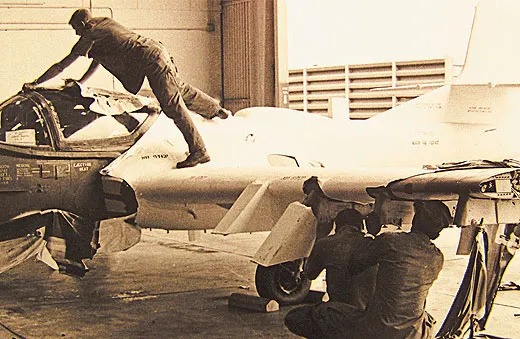

By nine months in country, the 604th had completed an astounding 10,000 sorties. The numbers reflect the fact that the A-37 could be turned around in as little as 90 minutes. The Cessna had none of the muscle fighter's high-maintenance temperament. "The two-to-one ratio of maintenance to flying hours was fantastic," crew chief Bill McCall explained in Branson. "An F-101 was something like 12 to 1. Give me two A-37s and I could literally keep them flying day and night."

Cessna's design concept was "walk-around maintenance," with multiple access panels in strategic locations. Switching out a powerplant took less than an hour—though the low-ride A-37 was certainly the only fighter that had to be jacked up to drop an engine. It was so low, in fact, that its engines were especially prone to hoovering up runway crumbs. Quirky, hydraulically actuated foreign-object screens filtered the jet intakes. They retracted at liftoff, but could be redeployed as needed. After missions, maintainers would clear the screens of stones, sticks, and a random sample of Vietnamese vegetation.

Another perk peculiar to A-37s was the option of single-engine cruise. At the time, it was the only Air Force jet authorized to shut down an engine in non-emergency conditions. Cruising on one burner conserved fuel for more loiter time above the target. Several pilots told me that snuffing a perfectly good jet engine at 25,000 feet could be unsettling, but no one recalled ever failing to get a relight.

The second seat, a T-37 carryover, generally went unoccupied. But not always. "I spent a lot of time with VIPs beside me," said Lloyd Langston. After Combat Dragon, deployments to the 604th continued Weber's "Everyman" theme. A-37 pilot Wayne Moorhead declined his first assignment in F-105s to complete a master's degree in industrial studies. "It wasn't like we were career fighter pilots," he said at the reunion. "What's phenomenal is, we were a conglomerate of average pilots from all backgrounds."

The career-minded, however, faced the challenge of using "Super Tweet" and "mini-gun" in the same sentence and still sounding like brigadier general material. Dragonfly experience wasn't the résumé enhancement that Heavy Metal flying was. "You had a big speed bump on your record to get over," Robert Macaluso admitted. "You weren't accepted as a real fighter pilot." There were exceptions: John Blaha rose from A-37s to command space shuttles, and Lieutenant General John Bradley, with half of his 7,000 hours in A-37s, became chief of the Air Force Reserve. Bradley remembers the sting his squadron mates felt in 1971 when Stars & Stripes recognized an F-4 unit for a "phenomenal" 680 sorties in a month. "We said to each other, ‘Man, we just flew 1,200,' " he said.

One reason the Super Tweet didn't make headlines—and didn't suffer heavy casualties—is that it didn't fly into North Vietnam, where over the course of the war, air defenses claimed almost 200 F-4s and 300 F-105s. It stayed in the south—and in Laos and Cambodia—where U.S. ground forces were fighting.

When A-37 pilots remember the war, they talk about protecting "the guys on the ground." Before deployment to Vietnam, Major Richard Martel made one request of the Air Force: "I really don't want to kill people." He applied for an unarmed reconnaissance aircraft. But Martel was a computer specialist who flew a T-33 trainer weekly just to keep his skills sharp. Another candidate for Lou Weber's 604th. At the reunion banquet, the staff was stacking chairs and yanking tablecloths from under our drinks when Martel told me about the ironic path from his request to a Silver Star.

On November 29, 1967, he found himself far from his first-choice assignment, piloting one of two heavily armed A-37s circling atop a stack of Super Sabres at midnight. On the ground 16,000 feet below, in a place called Bu Dop, a special forces air base was under siege by Viet Cong hunkered down in thick jungle. The F-100s rolled in, bombing and strafing, then left the area. Despite the pounding, an anxious forward air controller alerted Martel to a multitude of Viet Cong massing for a final assault. Only the two A-37s remained above the target, both carrying 250- and 500-pound bombs plus six tubes of CBUs—anti-personnel cluster bomb units. Martel radioed the other Dragonfly pilot to extinguish his navigation lights and rotating beacon, then flipped his CBU switches to "HOT."

"We're going down now, lights out, " he told the FAC.

"We're gliding down from altitude completely dark with our throttles pulled all the way back to idle," he recalled. "It's pitch black. The VC think everybody's gone home. They can't see us. They can't even hear us. I dove the last 6,000 to the deck and leveled out at 100 feet. But that's nothing in an A-37."

Tracers from Russian-made 12.7-mm guns swarmed him as he methodically dispersed cluster bombs from rock-throwing altitude. He laid them in a swath 300 meters long. Flying a racetrack pattern, his wingman followed, also strewing the bomb units.

The ambivalent combatant, whose one request was duty in a non-lethal aircraft, paused for an instant four decades later. "We killed them all," he continued quietly. "We killed over 200 of them on one run." Both A-37s climbed away, then returned to take out gun emplacements with hard bombs. "The base was saved," Martel said, regaining his all-in-a-day's-work tone. "And we picked up a little medal." His Silver Star recommendation describes "Outstanding bravery...in the face of the heaviest ground fire anyone has ever received in this area of operations."

On the hotel patio, guests craned their necks to watch four attack aircraft ("A-10s," I heard someone grumble) execute a flyover in honor of Lou Weber and the A-37 vets. The $400,000 Dragonfly gave up its role to the $8 million (in 1980 dollars) Warthog. Dragonflys went to Air National Guard units as OA-37 observation craft. Today, many perform counterinsurgency and drug interdiction for Latin American nations, and until recently, some served in South Korea.

Cessna's A-37 never got the girl or the movie deal, but from 1967 to 1974, the Air Force reports, the airplane flew 68,471 missions. Pilots whose squadrons flew 1,000 missions a month consider the figure low.

The work ethic of America's most unhyped combat jet often extended right up to a pilot's final sortie. In a noisy hotel hospitality suite in Branson, Bob Chappelear described his last day in Vietnam. He had flown 475 missions, so I expected tales of fighter pilot-esque revelry—the cork-popping champagne send-off. Instead, just hours from boarding a Boeing 707 that would get him "back in the world," he opted for an all-nighter racking up numbers 476 to 478. Two scrambles after midnight and a shake-and-bake dropping Snake Eye bombs and napalm at daybreak. Then, he landed the A-37 and walked away.

"I just grabbed a quick shower, put on my uniform, and packed my bags," Chappelear said. "Caught the Freedom Bird and came on home."

Frequent contributor Stephen Joiner writes about aviation from his home in southern California.