A rare da Vinci codex on birdflight goes on display at the National Air and Space Museum

Leonardo da Vinci, Birdwatcher

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/DaVinciCodex-631.jpg)

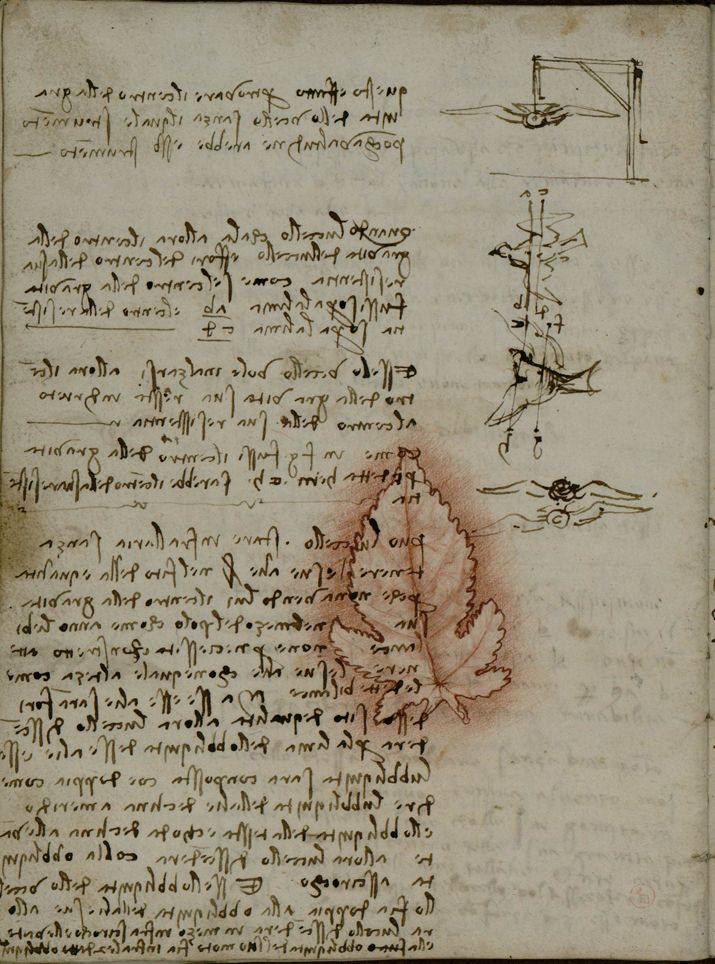

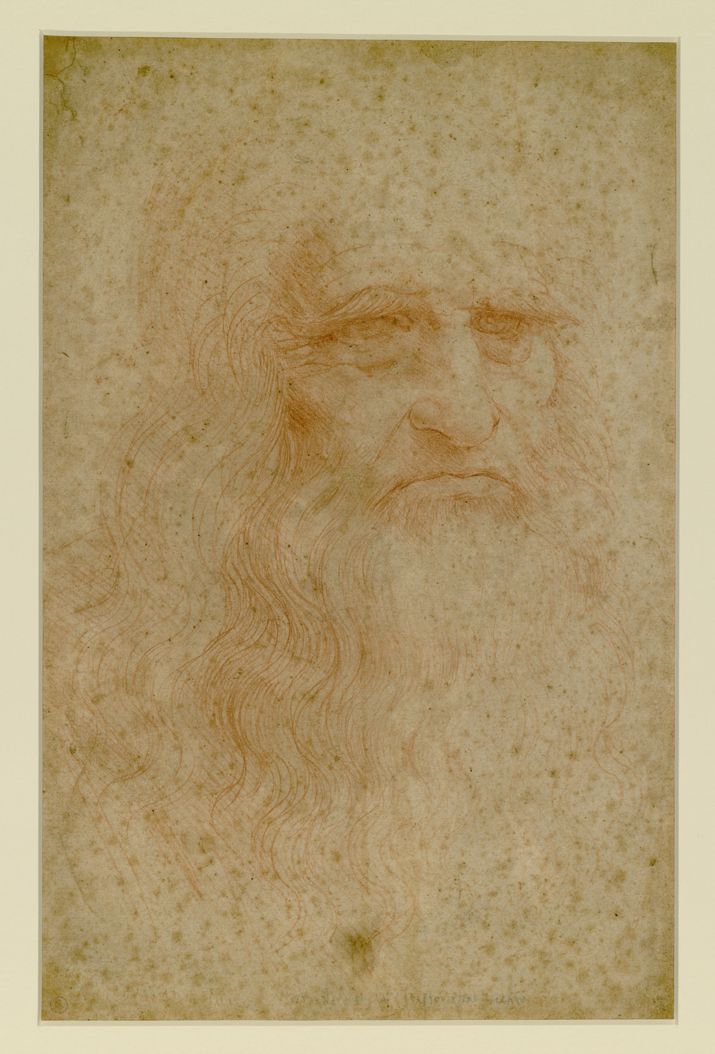

At first glance, it’s a jumble of disconnected information: how to crush diamonds, how to mix paints of strong blue or red, observations on the flight of birds. But this small notebook—18 sheets of fragile parchment covered with an almost illegible hand in brown ink and sketches in red chalk—may be among the most famous in the world.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex on the Flight of Birds, compiled by the artist between 1505 and 1506, has been seen by the public in this century only rarely. After a brief exhibit at Moscow’s Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, the codex will be on display for 40 days—starting September 13—at the National Air and Space Museum.

“Any materials associated with Leonardo da Vinci are extraordinary,” says Peter Jakab, associate director of the Museum, “and any museum would want to display anything associated with Leonardo. But Leonardo items just don’t come to the United States very often.”

The codex was last shown in the United States—in Birmingham, Alabama, and San Francisco, California—in 2008. When it finishes touring, it will return to the Biblioteca Reale in Turin, Italy, and go into storage for a minimum of 10 years.

“So while this isn’t a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity [to see the codex], it’s pretty darn close,” says Jakab.

The exhibit, funded by the Embassy of Italy, is part of a year-long celebration titled “Italy in the US 2013: The Year of Italian Culture in the United States.” The codex will be displayed in a case within the Wright Brothers & the Invention of the Aerial Age gallery, along with two kiosks that will allow visitors to scroll through high-definition reproductions of the codex’s 18 pages.

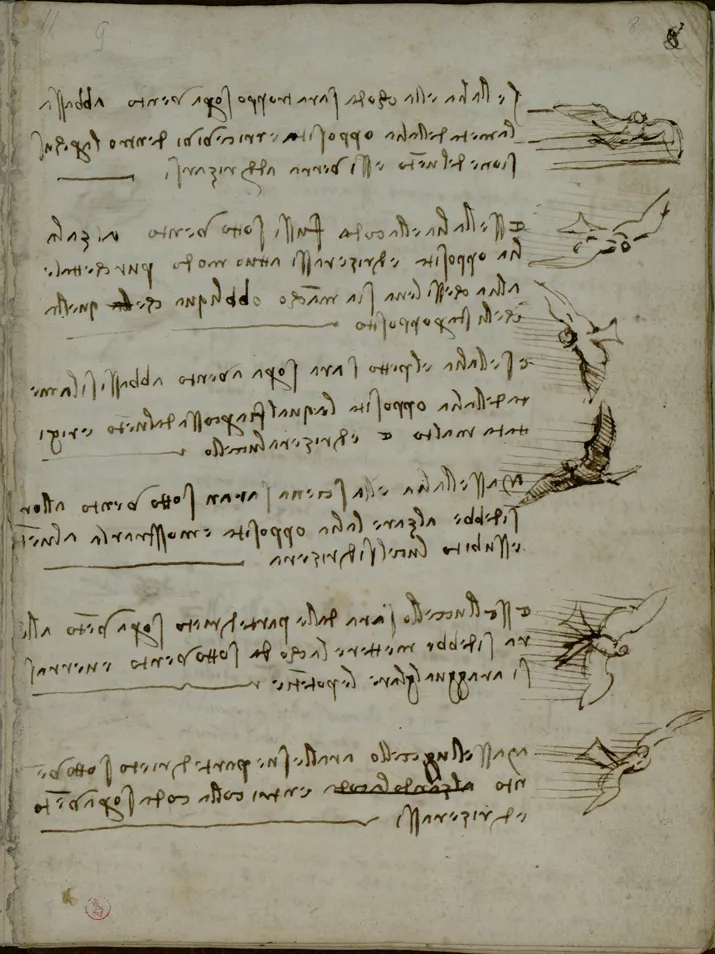

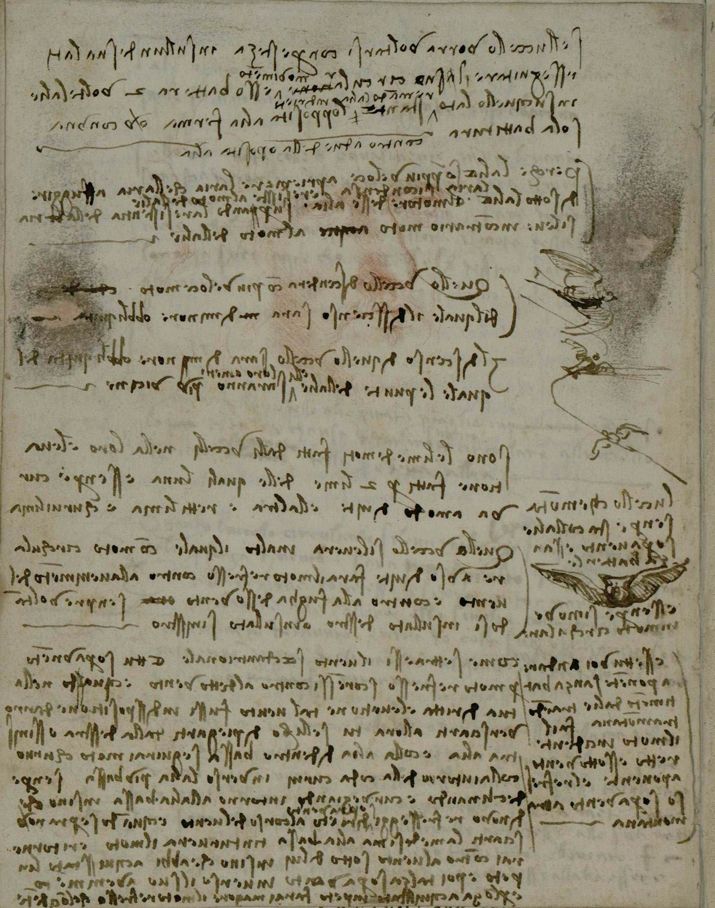

By 1505, da Vinci had conceived of and sketched various types of human-powered flight, including a flying machine with huge, bat-like wings (his ornithopter); a parachute-type device made of linen; and a small platform—made of wood, reeds, and taffeta—upon which a man would fly prone.

The painter was a birdwatcher, and consumed with the idea of flight. In the codex he gathers his thoughts on the anatomy of birds, how wings compress the air, and the importance of wind to a bird’s ascent or descent. He also explores the flapping-wing flight of smaller birds such as kites and larks, versus the gliding, thermal-riding technique more commonly used by raptors.

The codex was first published in English in 1893; an excerpt appeared in the 1895 edition of The Aeronautical Annual, published in Boston, Massachusetts.

The Wright brothers were familiar with da Vinci’s work: In a 1920 deposition, Orville noted: “We were much impressed with the great number of people who had given thought to it [the problem of flight], among these some of the greatest minds the world has produced. But we found that the experiments of one after another had failed. Among these who had worked on the problem I must mention Leonardo Vinci, one of the greatest artists and engineers of all time….”

German glider innovator Otto Lilienthal was also intrigued with da Vinci’s ideas. And French-born aviation pioneer Octave Chanute made note of da Vinci’s diagrams in his 1894 work Progress in Flying Machines.

“Da Vinci was completely focused on flapping-wing, human-powered devices, which were not physiologically feasible for humans,” says Jakab. “But his ideas do reflect that someone of his scientific genius and capacity was thinking about flight in this period.”

The codex has an interesting history: It originally went to Francesco Melzi, da Vinci’s pupil and heir. In 1637, 13 manuscripts, including the codex, were donated to the Ambrosian Library in Milan. But in 1797, Napoleon ordered all of the library’s da Vinci manuscripts sent to Paris. At some point between 1841 and 1844, the codex was taken apart and several of the folios stolen. They eventually resurfaced in London, and were returned to Italy. The codex was not rebound until 1967.

“The opportunity to have on public view an original da Vinci manuscript—particularly in the United States—is exceedingly rare,” says Jakab. “It’s really something to be able to say that you’ve seen something that was created by the hand of da Vinci.”