Letter From Bagram

Occasional dispatches from our man in Afghanistan.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/astan-flash.jpg)

U.S. Air Force Lt. Col. John Sotham, a former Air & Space editor, recently served with the 455th Expeditionary Force Support Squadron, 455th Air Expeditionary Wing, at Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan. He reported back to us when time allowed:

Going Home (Posted Feb. 26, 2009)

I’m returning to this blog after what seems like a short time, but really hasn’t been. What with returning to the States, taking time off, returning to my job, and sliding right into the holiday season...how did it get to be February? I can’t believe I’ve been home for five months. I honestly can’t remember much about the three weeks after I returned—I slept a lot, and found it much harder than I thought it would be to readjust to normal life. I’m fortunate to live in south Florida, but going outside for the first week or so was an assault on the eyes. The tropical palette! The technicolor palm trees and cobalt skies overtaxed my tired brain.

I left Afghanistan the night of September 9, 2008, after spending a full day briefing my replacement, the new commander of the 455th Expeditionary Force Support Squadron, Lt. Col. “Deacon” Jones, who had arrived three days earlier. The handoff is exhausting—you’re working current issues right up to the last day, while trying to set up the new guy with everything he needs. I grabbed a few last items from my office in the old Soviet tower, said a few goodbyes, and dragged my gear to the passenger terminal. For the next several hours, those slated for my flight did what GIs have done since the time of the broadsword: We waited. We slumped in chairs, we slept on the floor, we paced. By 2300 (11:00 pm) we were outside in a large gaggle amid a sea of weapons cases and duffle bags, about to go through customs inspections, which required us to dump everything into bins. U.S. Army inspectors in surgical gloves looked for contraband—opium, seized weapons, ammunition, or war prizes.

We repacked and hauled our bags to a cargo pallet. After another few hours, we formed a long line across the darkened flightline to the C-17 and trudged up the cargo ramp. When arriving or departing the theater, you’re required to wear your helmet and flak vest on aircraft, so you try to find a seat and get reasonably comfortable. The flak vest rode up on my thighs, and I felt like a turtle. Once the rear cargo door is closed, only the dim lights inside the fuselage remain. You can’t see outside, so once the aircraft starts to roll, your only indication that you’re ready to go is when the engine noise rises to a bone-shaking roar. The pilots released the brakes and we were bumping, rattling, and hurtling into the night along Bagram’s seized, reused, and partially resurfaced runway. I cursed the Soviets with each kidney-pounding bump. Then it all stopped and we headed upward in a hurry. The sheer mountain peaks ahead of us were no match for the C-17’s powerful turbofans; I’d watched hundreds of the gray cargo haulers stand on their tails as they took off—less to get over the mountains than to quickly get as high as possible to avoid potential groundfire once the aircraft crossed the airfield fenceline.

We leveled off for a few minutes, then did a steep descent into Kabul. We picked up another group of airmen and soldiers, and very shortly we were headed for Manas Air Base in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. We were required to stay geared-up and in our seats until we cleared the airspace over Afghanistan, but a few rogues began to move around. The loadmaster got on the PA and made a few angry commands to sit down; the rogues heeded her, but only for a few minutes at a time. I’ve had similar experiences as a parent. And like any no-nonsense mom, the loadmaster knew how to handle things. After another five or so knuckleheads got up to stretch their legs, the C-17 did a violent pitch-up, then a sickeningly fast back-and-forth roll. Those who had been out of their seats, once they got off the floor, sat down and buckled in mucho-fast. Our split-second airshow, caused by a quick flick of the wrist from the flight deck, made me think of a Far Side cartoon that featured pilots giggling over their self-induced “turbulence.”

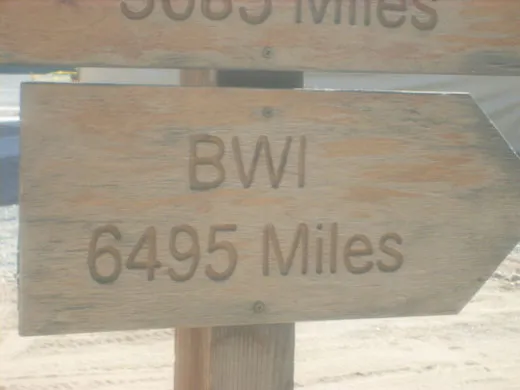

Kyrgyzstan was a respite. I turned in my gear, strolled around the Kyrgyz shops, and slept the first afternoon away—I woke sweaty once the sun began to heat up the transient tent I was in, but knowing I was going home, along with the sudden stress relief of not being in charge anymore, made me more relaxed than I’d been in months. I went for a jog. I ate. It was wonderful. The relaxation continued on our World Airways DC-10—so civilized after riding in C-17s. I leaned my head against the window and alternately dozed and watched the scenery go by. The Caspian Sea. The moonscape of Turkey after we stopped at Incirlik Air Base outside Adana. Then Europe’s lush greenery and a stop at Ramstein Air Base, Germany. The sun dropped over the Atlantic in a Hollywood sunset as we set out for the final leg to the United States. I awoke during the final approach to Baltimore.

The jetway was stuck—what an anticlimax. We could see the ground crew whacking the base of it with something. Then they took the universal stance of helplessness in the face of things mechanical: They stood around with their hands on their hips. Many groans filled the cabin—and some salty GI bitching—as everyone returned to their seats and we taxied to another gate.

My good friend Mark met me with some takeout food from my favorite deli in Annapolis—and with a few rum miniatures to toast the trip home. We hung out in the USO for about five hours until I could board my final leg to Fort Lauderdale. I made my way through the TSA checkpoint to the gate. I put my stuff in a bin and strode forward. Beep. After a few back-and-forths, I had to remove my boots, which were still filthy with Afghanistan dirt. I was angry. And it was September 11, no less. The guy explained that usually they didn’t require service members to remove anything, unless of course you couldn’t get through the metal detector. I fumed. As I put my boots back on, an older TSA guy asked me what I did in the Air Force. He told me how glad he was that today’s returning GIs were greeted with good wishes—not the welcome he had gotten when he returned from Vietnam. We chatted for a few minutes, and exchanged thanks for each other’s service. A life lesson just when I needed it. My anger evaporated and I went to my gate.

Before I knew it, I was walking down the jetway in Fort Lauderdale. I emerged into the terminal and dropped to one knee. My son, Ian, and daughter, Eve, hit me like little linebackers. My wife, Margaret, threw her arms around us all. I cried. They cried. The passengers waiting to board broke into applause. Time stopped.

I don’t know what to think about Afghanistan. Defense Secretary Robert Gates recently spoke of lowering our expectations, even as we prepare to send thousands more troops there. And what are we trying to accomplish? I remember standing in line one day along the road, waiting for the slow approach of a Humvee with “transfer cases” carrying two dead U.S. GIs. I watched two Afghan workers in our camp and we realized they weren’t affected in any way; they slowly poked their shovels into the dirt as they prepared a foundation for a new barracks that would be made from shipping containers. Others slumped indifferently inside the concrete bunkers nearby. There are towns in Europe that still honor the memories of long-ago battles and American dead. The bodies of two kids—barely out of high school—passed before us. The workers loafed. I was angry.

Time has provided some clarity, though. If we closed the base, most likely the Taliban or other ACMs (anti-coalition militants) would quickly fill the void and the workers would simply realign with whatever force took our place and paid a decent wage. Or they would be threatened into compliance. Even around Bagram, the largest base in Afghanistan, the Taliban were present. And sometimes they attacked. During my stay, a few rockets landed inside the base, and one night we had small arms fire from a band of militants trying to probe the perimeter. As a small firefight ensued, we ran for cover and donned our flak vests and helmets. So even around Bagram, where the surrounding villages provided workers, our influence was fragile. And across the expanse of desert, another village nearby had no such allegiance to us.

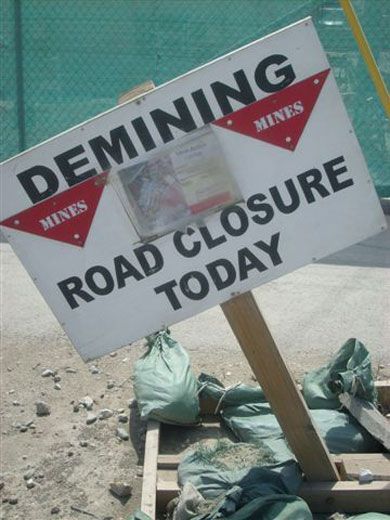

On the Edge of a Minefield (Posted Aug. 27, 2008)

I was out in a barren part of the airfield today. We were checking out some conex boxes (shipping containers) that have some of our equipment in them. They’re stacked in one of the old Soviet bunker areas—where they parked aircraft and stored munitions. There had been a dust storm all day and the wind was wicked. I took my weapon off so I could shimmy under the gate of the area we needed to get into. The 30-40 mph wind promptly blew the shipping manifests I had in my hands across the road and into more bunkers. I took off running after them. When you drop something and the wind takes it, you just take off—it’s a Pavlovian response.

I was bolting across the road as the papers blew toward one of the uncleared minefields. I suddenly remembered what the hell I was doing and stopped. The papers plastered themselves across a barbed wire fence short of the field, and I gingerly retrieved them. Mainly because of the fighting this area saw during the Soviet-Afghan war of the 1980s, Bagram is littered with mines and unexploded ordnance. The “no-go” areas are indicated with triangular red signs and other markers. There are also countless hulks of Soviet tanks, armored personnel carriers, and even aircraft scattered across the fields next to the runway and around the base—the Soviets suffered their final defeat in a desolate mountain pass not far from here. The mines and ordnance don’t seem to concern the locals who live outside the base perimeter. They live simply, in adobe dwellings made from the brown, finely powdered soil, and they tend to their farm animals in many of the same areas that are still uncleared.

Fallen Comrade (Posted Aug. 27, 2008)

Bagram is the main hub for air travel into and out of Afghanistan, which means it’s also the departure point for the remains of military members killed in action who are being sent back to the States. When remains are readied for the trip to an awaiting C-17, we hold what is called a Fallen Comrade Ceremony, which is usually announced over the loudspeakers about 6 hours ahead. Fallen Comrades mean you report to the road on the way to the flightline, regardless of the time of day or night, in uniform. We line the road and salute in unison as the remains are carried past, usually in the bed of a Humvee.

One ceremony was especially poignant for me. Designated time for us to line the road was 00:00, or midnight. The time was near, and everyone was silent and at parade rest—feet shoulder-width apart, and hands clasped behind your back. In the darkness, the only thing I could hear was the wind. The vehicles came around the corner and down our road—they go very slow, almost walking speed. We came to attention and saluted. There was a light in the back of the Humvee that illuminated the flag-draped transfer case; in the dark, the colors of the flag were absolutely brilliant as it passed in a pool of light.

Visible in the glow was a soldier slumped forward in the bed with the case; I don’t know if he was the squad leader, a buddy, or what. He had the far-away look of someone in grief—despite his combat gear, he looked lost, like a little boy. One of my Airmen who has been having a hard time with these ceremonies was visibly upset; I talked to her briefly and squeezed her arm. She smiled a smile that told me she’d be okay. As always, once the vehicles pass, it’s time to put the experience behind you and go back to work.

Arriving (Posted Aug. 15, 2008)

Have been here about two months. It’s a long, painful trip to get here. Military charters all the way, which means you leapfrog and stop where there are troops to pick up. Miami to Norfolk, Virginia, to Volk Field, Wisconsin, where we picked up half a planeload of soldiers.

We were on a World Airways DC-10 that still felt like a regular passenger jet, because, well…it was. But the troops didn’t get the memo, and brought all their weapons on board. It was 3:45 in the morning, and the crew just wanted to get the doors closed and leave. So the Army guys commence to stuffing their gear under the seats. The flight attendants drew the line at the overhead bins. Actually heard on the PA: “Please ensure the muzzles of your weapons are not sticking out into the aisles. Oh, and put your tray table up.”

We stopped for fuel in Bangor, Maine, where we were met by an amazing group of Americans—the Maine Troop Greeters. Since the days after 2001, these volunteers—many of them veterans—have met nearly every planeload of troops either going to, or coming from, Iraq and Afghanistan and other points overseas. At all hours of the day and night. They offer free cell phones to call home, along with coffee, doughnuts, and general warmth and good wishes. After our short stay in the terminal, they stood in line and shook every soldier’s and airman’s hand as we re-boarded the aircraft. An elderly man shook my hand hard and offered a simple, “See you when you come home, Colonel. We’ll be here.”

After we landed in Leipzig, Germany, we got the news that the aircraft had maintenance problems, and we’d have to spend the night—in a hangar that usually houses snow removal equipment. But the German airfield operations crew was good to us. They served us inflight meals for dinner—anything was welcome at this point—and a hot, catered breakfast and lunch the next day until we could reboard.

Next stop: Manas Airbase, Kyrgyzstan, which is where we picked up our body armor and awaited our C-17 to Bagram. There are thousands of troops transiting Manas, so you sleep in a transient tent—mine was full of U.S. Army and Czech troops. Everyone’s toting so much gear that even walking space near the bunks can be tight. The Czechs piled their rifles on a spare cot to make room.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sotham_photo.jpg)