The Likelihood of Life on Venus Just Increased Dramatically

A sample-return mission to our planetary neighbor should now be considered.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/36/39/3639ae43-1da4-4ad3-8c65-8ab06cc4cf09/artist_s_concept_of_lightning_on_venus.jpg)

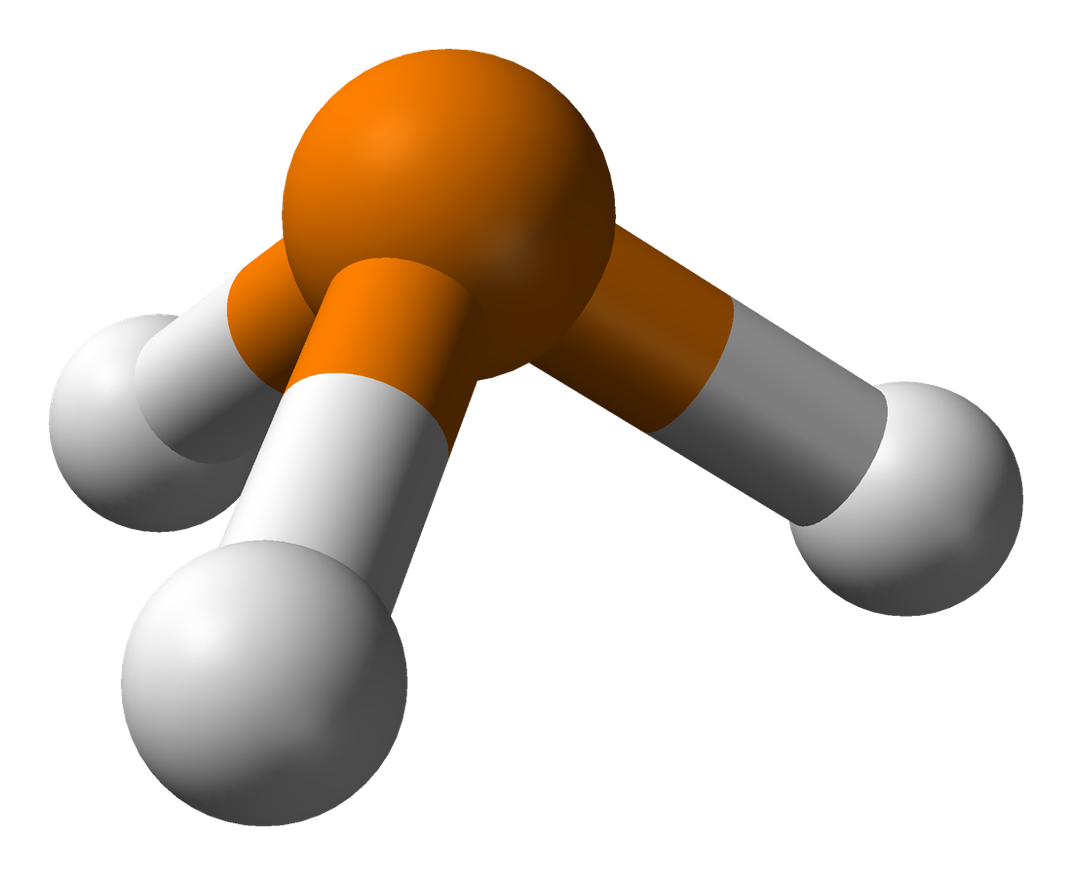

Jane Greaves from Cardiff University in the U.K. and several co-authors, including some from MIT, just announced in an exciting new paper the discovery of phosphine gas in the clouds of Venus. Astrobiologists have long sought to detect a “biosignature” that would prove the presence of life on another world beside Earth. This finding falls short of that ambitious and elusive goal, but it may be the closest we’ve come yet.

The authors detected phosphine in the Venusian atmosphere at a concentration of about 20 parts per billion, using thorough spectral analysis and observations from two different Earth-based telescopes in 2017 and 2019.

In a paper published earlier this year, some members of the same team identified phosphine as an ideal biosignature gas to detect life on exoplanets, because it has uniquely identifiable spectral features and lacks “abiotic” false positives—meaning that no non-biological explanations are known that could account for measurable concentrations in a planet’s atmosphere. In that earlier paper, however, they pointed out that phosphine could be difficult to detect on another world, given the low amounts that would be likely to exist, its reactivity with other chemical compounds, and its vulnerability to being broken apart by ultraviolet irradiation.

It’s all the more surprising, then, that phosphine was detected in the Venusian clouds, where high amounts of UV irradiation and at least some radicals are present, which would destroy (oxidize) the gas rather rapidly. That means there must be something continuously replenishing the phosphine.

What, though? On Earth, this colorless gas, which is toxic to humans and other mammals, is produced by microbes living under oxygen-free conditions. The authors took a Sherlock Holmes-type approach to searching for other explanations for the phosphine detected on Venus: try the most obvious possibilities first. They tested for various chemical reaction pathways in the atmosphere and on the surface, including reactions induced by light, and couldn’t explain the high concentrations that were observed. Lightning, which has been reported to occur on Venus, couldn’t explain it either. They even considered the possibility that the phosphine was delivered by asteroids or comets, but again, the calculated values were way too low. Besides, radar images of the Venusian surface didn’t show a recent major impact. That left biology in the clouds of Venus, or some unknown geochemical or photochemical process, as the only explanations.

The possible presence of a Venusian aerial biosphere has been suggested by several authors, including me, and most recently, by Sara Seager and co-authors, some of whom are also authors on this new paper. Environmental conditions in the clouds of Venus are extremely harsh, but may not have been at earlier times in the planet’s history, meaning that microbial life might have had time to adapt.

There is one other intriguing detail about the new finding. Phosphine was detected near the equatorial and temperate latitudes, but not in the polar area. As the authors point out, this would be consistent with a biological explanation, because the atmospheric circulation patterns in the mid-latitudes would offer the most stable environment for life.

So where does this leave us? The presence of phosphine in the oxidizing atmosphere of Venus is just astounding, especially because the gas has not been detected previously on any other terrestrial planet beside Earth. Unfortunately, that does not prove the presence of biology. There are many unknowns about our “twin planet,” and many processes and chemical reactions we do not understand. Even if we accept the biological explanation, why would putative microbial life at Venus release phosphine into the atmosphere, when phosphorus is such a valuable and critical nutrient?

Nevertheless, as philosopher and astrobiologist Carol Cleland has pointed out, if we want to search for alien life, we have to look for anomalies. This new discovery is clearly an anomaly, and we need to investigate further. Sample return missions to the Venus atmosphere have been considered, at least conceptually, including a Stardust-type mission that could scoop up micrometers-sized aerosol particles in the cloud layer and bring them to Earth for analysis. Could these be microbes? Space agencies might want to consider moving up a Venus sample-return mission in the queue of planned missions. If life exists on Venus, it can only be in the clouds.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Dirk-Schulze-Makuch-headshot.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Dirk-Schulze-Makuch-headshot.jpg)