Lin Xu’s Obsession

It started with a search for images of his hometown in China. Hundreds of miles of film later, he can’t stop looking.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Lin-Xiu%20flash.jpg)

About five years ago, Lin Xu learned that film from the Lockheed U-2 reconnaissance aircraft had been declassified and given to the National Archives. A digital imaging expert at Eastman Kodak in Boston for 12 years, Xu decided to drive the eight hours from his home in Massachusetts to College Park, Maryland, and search the declassified material. He was hoping to find photographs of his hometown, Jilin City, China.

But there was a catch. Although the film itself had been declassified, the film’s indexes were not. To make matters worse, the film was accompanied by 20,000 pages of declassified documents, but the Central Intelligence Agency had blocked all film index references in them, making the footage virtually unsearchable.

Between 1962 and 1974, pilots from Taiwan in the Republic of China made 213 flights over mainland China, about 100 of which were over land. (Several years earlier, the Taiwanese government and the United States had agreed to cooperate on flights to gather intelligence about communist China.) Each mission generated up to two miles of film, and when the CIA delivered the declassified film to the National Archives, each roll was cut into 60 pieces. One of these pieces could have images of Jilin City, thought Xu (pronounced “shoo”).

He first searched the declassified mission documents for clues to which areas were overflown on each mission. He found missions that flew over geographic features, like Beijing’s city wall, and, by checking the time coordinates on the documents, he could connect missions to events, such as a MiG-21 chasing a U-2. He could then connect the events to sites overflown; that led him to find footage of Jilin City.

Although Xu had seen images of Jilin City taken by Corona satellites, the U-2 images were a revelation. The mission was flown in 1962—the earliest images of the city Xu had seen. His elementary and high schools hadn’t yet been built; that land, with its pigpens, retained a rural feel. Xu could even see the three-story apartment building where he grew up.

That was the moment when his own mission broadened from finding pictures of his hometown to creating his own index of the miles of filmstrips.

U-2 pilots didn’t turn on their cameras until right before entering the target area, so in his searches, Xu has to estimate where, relative to the film’s length, an incident happened, in order to request the appropriate film canister number.

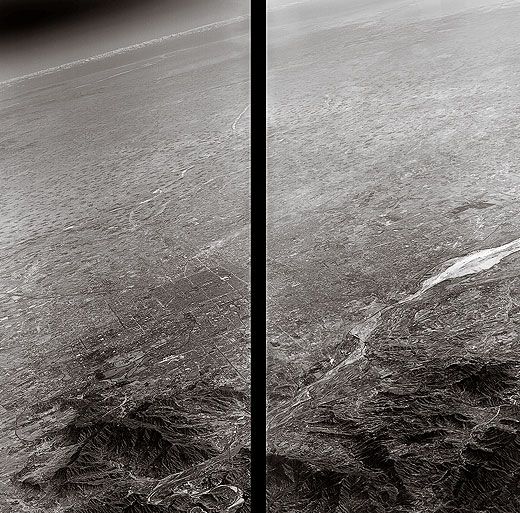

The U-2 footage is stored at the National Archives’ facility in Lenexa, Kansas, and researchers must place a shipping order—for no more than 10 canisters at a time—before arriving at Maryland. There are two cameras on a U-2, one on either side of the aircraft. Images from the two are joined to give photo interpreters a complete picture of the terrain (see photo, p. 38). “When you try and locate a target,” says Xu, “it could be on the left side of the film, or it could be on the right. So you have to order both sets. Out of the 10 cans, you actually have five chances to find your target.”

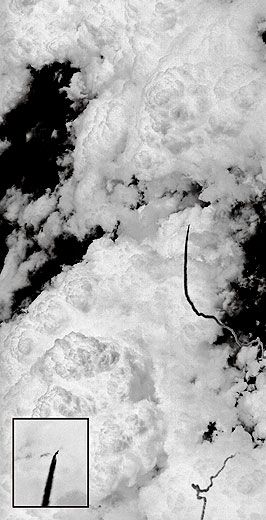

The film cannot be touched or scanned, and has to be viewed on cold war-era viewing tables, donated by the U.S. Air Force and the CIA. Each researcher must laboriously hand-wind the film. “If I look at 10 cans,” says Xu, “I’m winding 2,000 feet of film.” Xu became fascinated by the MiG pilots who chased the U-2 (see “I Was There: Bring Down the Spyplane,” p. 48), and started looking through the footage for the Soviet-designed fighters. But the MiGs were elusive quarries.

“I have to examine the film frame by frame, very carefully,” says Xu. “Most of it is ocean or clouds, and the plane could be hidden in a cloud. So you look from land to ocean, from ocean to cloud, and you try to find a black spot.” Finding the spot was especially difficult because the film is in negative. To make it more challenging, the MiG doesn’t leave a contrail. Xu’s search for another communist Chinese airplane, the Shenyang J-6, was far easier. “That plane is also very small,” says Xu, “but it has a contrail. So when you look for it, all of a sudden you see a straight line: of course [at the end of the line], that’s it.”

Over the years, Xu’s focus has changed. What began as a search for images of his hometown has turned into a hope for a photography exhibition—in China.

“I always want to see what China looked like when I was younger,” says Xu, who immigrated to the United States in 1990 and became a citizen in 2000. “The country’s ancient structures were greatly destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. There’s a lot of new construction. We can’t go back too far, but with the declassified films we can go back to the years when I was growing up. For example, I’ve always been fascinated by the city wall of Beijing. It was built about 500 years ago, and while much of it was torn down, sections remained. But during the Cultural Revolution, around 1967, they tore down most of what remained. The wall and a moat can be clearly seen on the U-2 photo. I’d like the Chinese to see what the country looked like before the Cultural Revolution.

“On the Chinese side,” he continues, “they put a tremendous amount of effort into bringing down those spyplanes. But they never saw the photos that were taken. Naturally, they’re interested in seeing what the U-2s were photographing, how their MiGs were chasing it, and where their missiles were firing.”

Asked to estimate how much time he’s spent on the project, Xu hesitates. “A hobby is a hobby,” he finally says. “Between driving eight hours to [Maryland], and looking at the film…I have no idea. In the past three years it has been a large amount of time.”

His most recent project involves people, not celluloid: Xu would like to introduce the Taiwanese U-2 pilots to the mainland Chinese operators of surface-to-air missiles who tried to shoot them down. “As far as I know, it hasn’t been done before. I’ll try my best,” he says.

You wouldn’t expect anything less from the man who has carefully scrutinized hundreds of miles of film, one frame at a time.

Rebecca Maksel is an Air & Space associate editor.