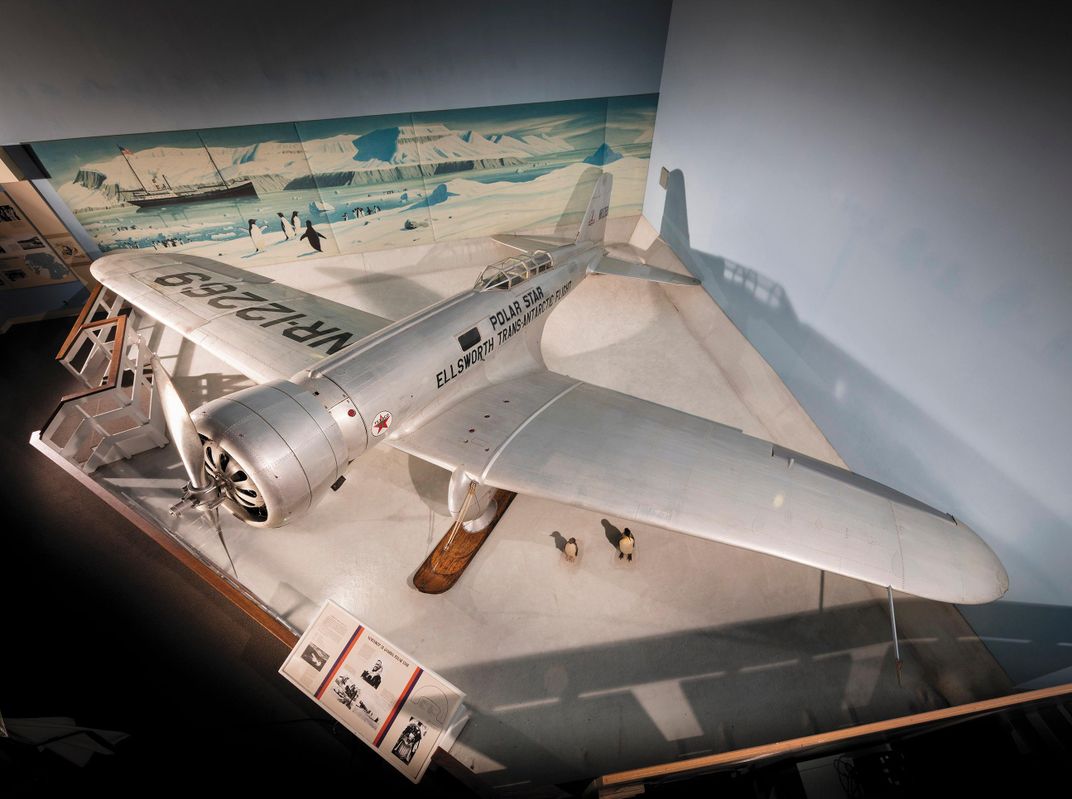

Lincoln Ellsworth’s Polar Star

Surveying Antarctica by air in 1935.

:focal(510x280:511x281)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4c/1b/4c1b7480-387a-44e3-a0e2-a8274261a5a1/16c_dj2017_nasm-9a08359_live-wr.jpg)

It all started with a penguin. In 1913, Lincoln Ellsworth, the son of a wealthy Chicago businessman, was in London, taking a course in geographical surveying at the Royal Geographic Society. Each week he visited the London Zoo to watch the emperor penguin that Ernest Shackleton had brought back from the Antarctic in 1909. “I used to watch the strange dignified bird for hours,” Ellsworth would later write. “Had it not been for that beautiful emperor penguin…I should probably never have chosen the polar regions as my field of endeavor.”

Ellsworth, an indifferent student, had left New York’s Columbia University 10 years earlier, and had spent the last several years conducting exploratory surveys for railroads and timber companies in Canada and the Yucatan. But after attending the memorial of Antarctic explorer Captain Robert Scott—and spending quality time with the penguin—Ellsworth was determined to become a polar explorer. He was 33 years old and finally had a purpose in life.

As early as 1914 Ellsworth championed the use of the airplane in polar exploration, meeting with Admiral Robert Peary to promote his idea. In order to become a pilot, Ellsworth entered the Curtiss Flying School in Norfolk, Virginia, but dropped out after a few days. He traveled to Paris, hoping to join the Lafayette Escadrille, but was rejected for being 14 years above the age limit; he was grudgingly admitted into the French air force as an observer. He trained in a Caudron biplane; Ellsworth spoke no French and the pilots spoke no English, so the training was non-verbal: “A poke in the back meant one thing,” he later wrote, “a rap on the head another.” He should have been sent to an observers’ training camp, but none were nearby, so Ellsworth continued to fly for three months, the only piloting he would ever do. He spent the rest of the war flying a desk.

But something good came out of Ellsworth’s time in Paris: he met Roald Amundsen, discoverer of the South Pole. In 1925, the two men, along with four other team members, attempted to fly from Norway to the North Pole in two Dornier Do J Wal flying boats. (Ellsworth’s father contributed $85,000 to the expedition.) Engine trouble forced them down 120 miles short of the pole. After 25 days on the ice, the crew flew their surviving flying boat to the coast of Spitzbergen, Norway, where they were rescued by a passing seal hunting ship.

The following year Ellsworth and Amundsen, along with 14 crew members and a dog, flew an airship—the Norge—over the North Pole, before landing in Alaska three days later.

After these adventures, Ellsworth considered his days as a polar explorer over. But inactivity didn’t suit him, and as airplanes became more dependable, Ellsworth decided to mount his own expedition, this time to Antarctica.

Antarctica, with an area the size of North America, was virtually unmapped. What better way to survey the huge landmass than by air?

Ellsworth needed an airplane sturdy enough to survive buffeting winds. High winds had tossed one of Admiral Byrd’s airplanes half a mile from its lashings, so he chose the all-metal Northrop Gamma, which had a low wing. It had wide skis that could be swapped with wheels or pontoons and, Ellsworth claimed, a cruising range of 5,000 miles. He named the airplane Polar Star and had it shipped from the United States to his base in Norway, where it was placed in the hold of the Wyatt Earp, a herring boat, along with two years’ worth of supplies.

Ellsworth had thoroughly examined the diaries of past Antarctic explorers, who had traveled by dogsled. He believed there were plenty of good landing fields for his aircraft, so he could make his trans-Antarctic flight in several passes; if he encountered bad weather, he could land and wait it out.

The Wyatt Earp arrived in the Bay of Whales on January 9, 1934; Ellsworth and pilot Bernt Balchen went aloft for a 30-minute trial flight. But that evening the Polar Star was caught in the ice and crushed; Ellsworth had to abandon his attempt and send the aircraft back to the United States for repairs.

In September 1934 the crew tried again, but during a three-month stay, the weather allowed less than 12 hours of flying time, leading a friend of Ellsworth’s to exclaim, “Your Polar Star has traveled farther and flown less than any other plane!”

In late 1935, Ellsworth made a third attempt, this time with a new pilot, Herbert Hollick-Kenyon, who was more willing to fly in iffy weather. On November 22, after 14 hours in the air, they made their first landing, crumpling the Polar Star’s fuselage in the process. Their radio was also broken; and in a final stroke of bad luck, the pair learned that their sextant readings had been incorrect and they were more than 200 miles off course.

Despite the fuselage damage, the Polar Star was able to fly, and the next day the two men took off. In only 30 minutes, low visibility forced them to land. After waiting several days for good weather, they took off again, hoping to find Little America, the camp Admiral Byrd had established in 1928, but after traveling only 90 miles, bad weather forced them to land again, and they had to wait out an eight-day blizzard. After the weather cleared, Ellsworth and Hollick-Kenyon had to dig out the Polar Star using the only item at hand: a teacup. After two more flights, the Polar Star’s fuel was exhausted. Ellsworth and Hollick-Kenyon walked the rest of the way to Little America, where they gorged on supplies left behind by Byrd. Every day for one month, Ellsworth hiked six miles to a meeting point he and the Wyatt Earp’s captain had pre-arranged, finally making contact with the ship.

Ellsworth received a special gold medal from Congress for his discovery of two mountain ranges and for claiming, on behalf of the United States, 350,000 square miles of Antarctic territory.

As for the Polar Star, it was rescued, then loaded onto the Wyatt Earp, which chugged up the coast of South America, through the Panama Canal, and on to New York. In April 1936, when Ellsworth saw the Polar Star lashed to the deck of the fishing boat, he wrote, “She was as good as new but far too dear a relic in my eyes to be permitted to grow old and go to aviation’s boneyard. So I presented her to the Smithsonian Institution.”

The Polar Star is currently on display in the Golden Age of Flight gallery in the Museum on the Mall.