What Ever Happened to the Men of Hawk Hill?

During the Vietnam War, the author reported on a Huey rescue mission. Forty-five years later, he tracked down the crew and the soldiers they saved.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9c/05/9c0533a0-cb34-400e-9e4c-07a64197a79e/31j_dj2016_dustoffhires_live.jpg)

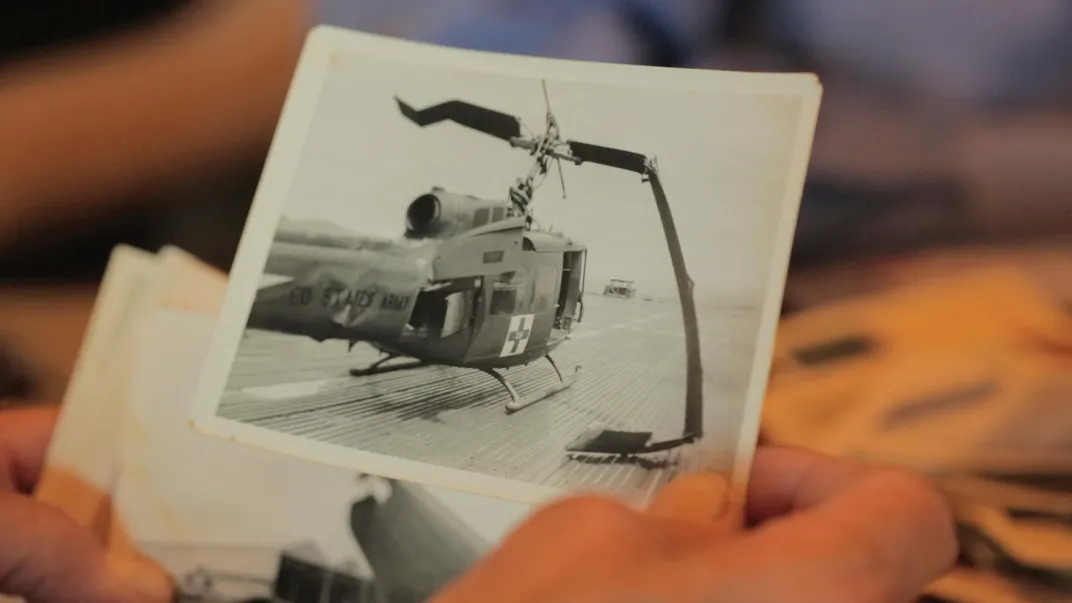

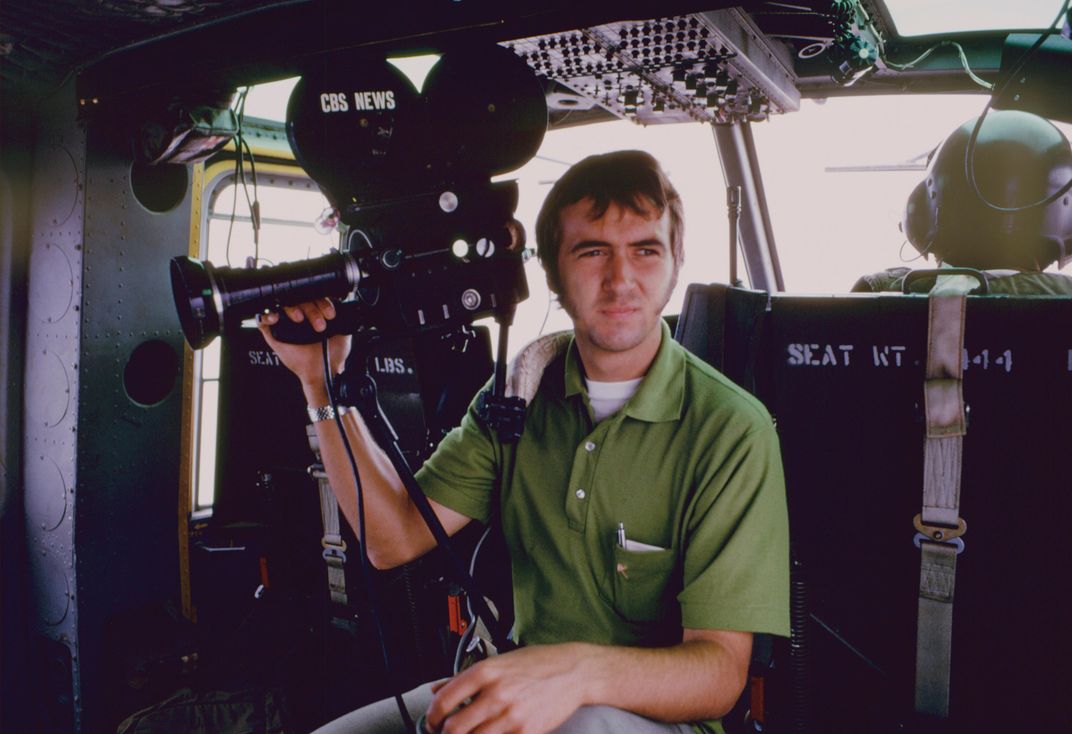

In 1971, during a six-month assignment in Vietnam for CBS News, I hitched a ride on a medevac mission flown from a dusty hilltop known as Hawk Hill. About 60 miles away, three soldiers were wounded and awaiting transport to the Hawk Hill emergency aid station, where they would be patched up and stabilized, then taken to a better-equipped hospital. It was one of an astounding 496,000 ambulance flights made during the war, and our news team—cameraman Greg Cooke, soundman Nguyen An, and I—got to go along.

Four days later, our story about that mission aired on the CBS Evening News, anchored by Walter Cronkite. The segment lasted more than seven minutes (an eternity by TV news standards), and the reaction to it back in the United States was extraordinary. Cronkite telexed the Saigon bureau: “superb…post broadcast phone calls indicate you hit home.”

In a 50-year career as a reporter, including long stints at CBS News and later ABC News, I covered other troubled precincts of the world where Americans were in harm’s way, but that medevac story has stayed with me. I knew I had witnessed something profound—an American ideal in action. Before racing off on a dangerous mission, no one on the crew asked what race the wounded were, what religion they followed, or what neighborhoods they hailed from. The only essential was that a fellow American was in trouble.

Some 40 years later, I discovered that I wasn’t the only one who continued to think back on that day. In 2011, the pilot on the mission, Bob Brady, got in touch with me through Facebook. About a year after that, another pilot we had interviewed—Ken Miller, the medevac unit’s operations chief—contacted me. Miller, who in 1971 had spoken thoughtfully about flying the missions known as Dustoffs, says today that medevac service “erased much of the ambivalence” he and many others felt about the war. “It was easy to say ‘We’ll risk our lives for one of our comrades,’ ” he says. “I didn’t have any ambivalence about that.”

Brady and Miller had called just to catch up, and when I told them I’d recently been to Vietnam, they were eager to hear more. In 2011 and 2012, a cruise line had hired me to lecture about my experiences during the war. I told the two pilots that what I saw would shock them: golf courses, luxury hotels, high-rise office buildings—all vastly different from our earlier experience.

But I was eager to hear how they and the others involved in the rescue had gotten on with their lives. Brady had become a defense attorney; Miller, a psychologist. Medic Delmar Pickett III became an artist, and Brady’s copilot, Dan Stephenson, who, like Brady, was less than a year out of his teens when I first met him, is an osteopath. But like many Vietnam vets, some had lived two lives, handling jobs while struggling with post-traumatic stress disorder.

When I talked to Brady and Miller, I was no longer a reporter—I’d become a writer and lecturer—but I still knew a good story when I heard one. I suggested that I find the men whom the aircrew had saved that day and make a documentary film about what had happened to the small group of veterans who 40 years earlier had shared a life-changing experience.

Miller, the psychologist, was especially enthusiastic. Seizing upon what I had said to him on the phone—“You guys were heroes and nobody knows it”—he responded that at long last, Americans need to learn there were heroes in Vietnam, and that vets who still feel unappreciated also need to hear it. The documentary could accomplish that.

He made another point: Combat vets from Iraq and Afghanistan would likely benefit the most by hearing how vets from the earlier war are handling their lives. “I think there’s going to be a lot of the same stuff [shared by the two groups],” Miller said. “Why did I go? What was it for?

“I don’t think the country has any clue about the lasting impact that [war] has, and for some it’s a nightmare they won’t ever be able to put to bed. You can’t go into a combat situation and come back the same person.”

The starting point for the documentary is the segment that aired in 1971. This is what happened that day.

**********

“That’s life coming,” says Brian Feeheley of the sound an approaching Huey’s rotors made cutting through the air. On January 17, 1971, a booby trap ripped open his legs and wounded two of his buddies while they were on patrol north of Tam Ky, South Vietnam, with a unit of the 23rd Infantry Division, known as Americal.

The Huey’s mission—and every mission to rescue battlefield casualties—had to be carefully coordinated between the endangered units on the ground and the incoming helicopters; not only did the Americans know they could count on the arrival of medevacs, so did the enemy. “One of the most dangerous types of aviation in the ten year long war,” U.S. Army historians concluded in a 1982 study. The casualty count proved it: 470 medevac pilots and copilots killed or wounded, plus 666 other crew members killed or wounded, most by hostile fire or in crashes initiated by hostile fire. Other lives were lost in non-hostile crashes during evacuations, many at night or in bad weather.

The mission that rescued Private First Class Feeheley, as well as Staff Sergeant Jim Kessinich and Specialist 4th Grade William Formanack, from an enemy-infested ravine was a classic example of the dangers medevac crews often faced.

“Hey, something just hit us in the tail!” medic Delmar Pickett III cried out as the Bell UH-1 completed a looping left turn and swooped in toward a detonated canister of white smoke marking the landing zone.

Pilot Bob Brady was unrattled. Only 20 years old but already a veteran of numerous close calls, he calmly ordered: “Okay. Let’s go get ’em.”

Flying the right seat, copilot Dan Stephenson recited a constant flow of data, including airspeed and altitude, to aid his pilot. Brady sat the Huey down in a soggy rice paddy.

And get ’em they did.

Bursting out from their cover, a pack of infantrymen drenched in sweat and blood splashed through the rice paddy, hauling the two most seriously wounded in makeshift stretchers made of black ponchos that bounced and swayed with each laborious step. The third man, although bleeding from his chest, arm, and thigh, was able to walk to the Huey.

The medic and flight engineer scrambled to secure the wounded on board. The extraction took about a minute.

“Charger Dustoff,” Brady radioed to the aid station. “We’ve got three wounded on board.”

On liftoff, the medic spotted several uniformed North Vietnamese soldiers and returned their fire. The pop-pop-pop of automatic gunfire underscored the danger faced not only by the rescuers but also by those being rescued.

Many years later, Feeheley recalled the bitter irony of it all: “I was thinking, I get rescued and now I’m going to get shot down and die.”

The tension broke only once: One of the wounded guys, spotting our film camera, announced: “Hey, we’re going to be on TV!”

The three men would live. However, the pilot’s career almost didn’t survive. The brass was livid when word spread that Bob Brady (who would go on to fly over 800 missions during his year-long tour and receive a Purple Heart and a Distinguished Flying Cross) had allowed a news crew on the mission. He had neither asked for nor received anyone’s permission. We’d made our way to Hawk Hill in search of a good story, any good story, and simply asked the pilot if we could fly with him. Brady looked kind of bemused, as if I were a crazy man. “You want to fly with us? Sure. C’mon,” he said.

By the time Brady showed up in Saigon to face the music, the story had already aired, clearly showing Brady and his crew—and by extension all medevac crews—for what they really were. Heroes. Brady suffered no recriminations. “In fact,” he said recently, “everyone was quite pleased.”

After the mission, I interviewed the crew and other airmen in the unit, asking why they’d volunteered for Dustoff duty.(The term was the radio call sign for the first Army air ambulance service sent to Vietnam.) “I saw what it was like to be on the other end,” said Pickett, the medic. When he first came to Vietnam, Pickett had been with an infantry unit. After his unit came under attack and men were wounded, he watched the Dustoff crews operate. Though enemy were still in the area, “they [the medevacs] came in regardless. I was impressed. I was, you might say, flabbergasted. So I just volunteered.” Another young medic added, “This is the most positive thing going on in Vietnam right now.”

**********

In 2013, cameraman Greg Cooke and I headed out to find the men whose lives intersected ours that day. Cooke had been a staff producer at “60 Minutes” and later a cameraman, editor, and producer of “The Amazing Race,” among other hit shows. We traveled across the country on our own dime, without any clear idea if anyone would eventually broadcast the documentary. What came to matter most to us was learning that the veterans valued what we were doing. It validated their service to the country and, more important, their commitment and contribution to one another.

There were a few setbacks. The medic, Pickett, had died of natural causes the day before I called him to set up an interview. The crew chief we flew with couldn’t be found.

Catching up with Brady, the pilot, was a treat. He’d recently uprooted himself, shutting down his law practice and moving across the continent from Pennsylvania to California. Today, he lives in Thailand. With a laugh he’d earlier warned me that he was “really f----- up.” Most of the time he hid it well; he was a warm, charming, articulate guy with a giant personality. We could have done an hour documentary on him alone. The day we met up he was taking a flying lesson to hone his wartime skills. Greg and I, camera rolling, went along. Brady welcomed me with a large grin. “I didn’t kill you the last time you flew with me,” he said. “Let’s see what happens this time.”

Stephenson had also recently moved. An osteopathic physician, he was living in an RV in Washington State while tending to the rural poor at a health clinic. He was a man of many interests: He’d published a mystery novel, traveled the Pacific Northwest on thousand-mile motorcycle trips, and sailed on the ocean.

Both men had been seriously affected by PTSD. Like almost all of the veterans I interviewed, they suffered from survivors’ guilt and experienced flashbacks. They had problems developing and maintaining close relationships. Brady said shutting down emotionally was something he did in the cockpit during the war—“So I don’t die today. It’ll happen tomorrow”—and his emotional isolation intensified in civilian life. Stephenson reported that the unpredictability of combat stayed with him. “You couldn’t plan ahead and I can’t even today,” he said.

Both were divorced and trying to make new relationships work. Brady claimed he couldn’t remember how many times he’d married. I couldn’t tell if he was kidding.

The pilots had never met any of the hundreds of wounded they carried to safety, and were very excited to learn that for the documentary I planned to interview the three men who were part of our Vietnam story.

The problem was how to find them. And it was a big problem. I didn’t know their names or their units. Neither did the CBS News archives, because I hadn’t interviewed them on camera. One of my notebooks had disappeared. And—this is difficult for a reporter to admit—in the chaos of the mission, I don’t think I ever did ask the wounded men who they were. My excuse? The story’s centerpiece was to be the medevac crew.

After months of detective work, I was successful. I was aided by retired U.S. Army General Ray Bell, who discovered the Americal division had been operating in the general area of the rescue, and by Leslie Hines, an Americal historian who found a casualty report that appeared to contain the names I was searching for.

However, I wanted additional proof, and Greg Cooke came up with the clincher. He discovered a few frames of film, which hadn’t aired, of who we suspected was Staff Sergeant Jim Kessinich. An enlargement revealed the word “WAR” on a medallion the man wore. I emailed a close-up photo to Kessinich and asked “Could that be you?” Bingo! When we showed up to interview him for the documentary and introduced him to the pilot and copilot, he had the medallion with him.

Each of the reunions was filled with a sense of wondrous disbelief. Was this really happening? At our first stop, Jim Kessinich’s wife and daughter led the hug brigade. Stephenson, who was reluctant to talk about himself or the war, provided the first hint that what we’d begun was therapeutic. “Jim,” he said with prayer-like solemnity, “seeing you with your great family makes me feel for the first time I did good things.”

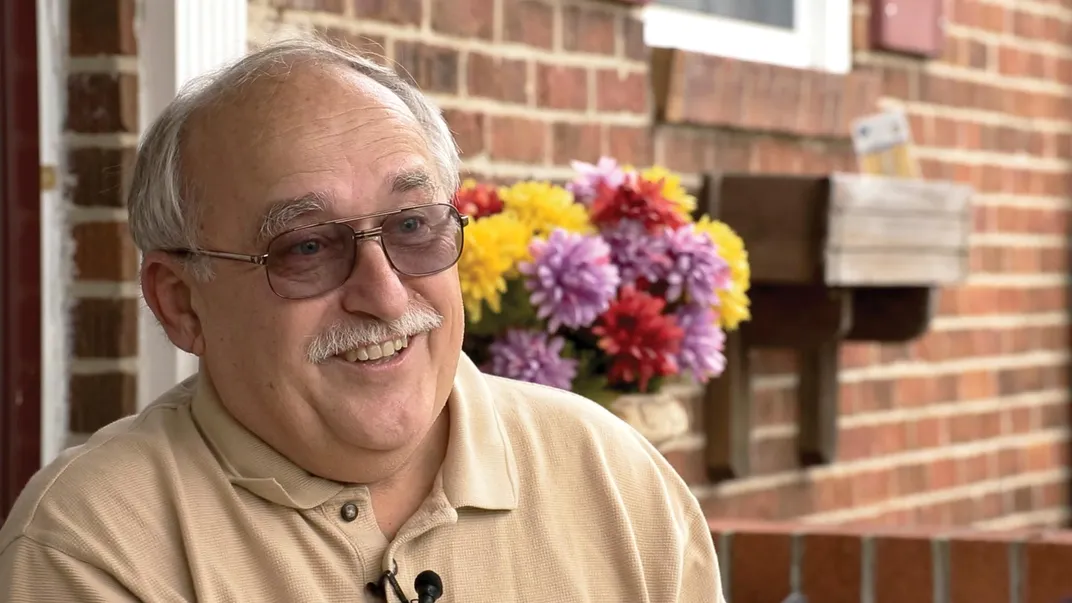

Kessinich, an Army lifer with a 26-year military career, frequently choked back tears. We all did. He had retired as a sergeant major, the highest enlisted rank in the U.S. Army, taught combat at West Point, and served in a presidential honor guard. Over the years he flew in many helicopters, and “every time” wondered whether his pilots were those who had rescued him.

For the wounded, the memories of that day in 1971 were still sharply in focus. “Saw the light…heard the boom,” recalled Formanack. “And then you feel like you’ve been kicked by a jackass,” said Feeheley. Formanack remembered that Feeheley, who triggered the device believed to have been a grenade while walking point, had apologized over and over.

Formanack, the most seriously wounded, endured some tough years: drank too much, had numerous surgeries, still has shrapnel in his upper body. Painful leg wounds forced him to give up the bar and restaurant he worked in and partly owned. All that was masked by his enthusiastic greeting; a firm handshake and a broad smile guiding Brady, Stephenson, Cooke, and me into a tidy, rural cottage to meet his wife.

Our reunion, which Formanack called “a very moving thing,” was capped by several deeply emotional, extraordinary moments. He recalled that during the flight, he reached out, seeking comfort, and I held his hand. As a memento of our visit, he asked for a photo of us clasping hands as we had done during that crisis so long ago.

His daughter Allison, home from graduate school to be there with us, told the pilot and copilot: “I just thought of this—I never would have been born if it hadn’t been for the two of you!”

There was something spiritual about the visits to each of the three soldiers who had been wounded that day. Brian Feeheley told us that almost daily he visits a Vietnam memorial in Maryland, etched with the names of war dead: “I just go to let them know they’re not forgotten.”

We filmed Brady and Feeheley at the memorial. Like old buddies, they discussed their problems with PTSD, admitting that, feeling too macho, they delayed getting therapy for much too long.

Feeheley, a longtime postal worker, said that 9/11 had almost “pushed me over the edge,” and that’s when he went to the Veterans Health Administration for help. He talked of having been suicidal. And in a moment of reverie, as the two old soldiers gazed at the names of the war dead, Feeheley said, “I keep thinking…how many more dead there would have been if there were no medevacs.”

The documentary, with the working title Vietnam Medevac, is in production. We’re hoping to find a distributor soon so that people will learn about the work of medevac crews and so that veterans of Vietnam and other wars will experience the brotherhood of this reunion.