The Impossible Flight

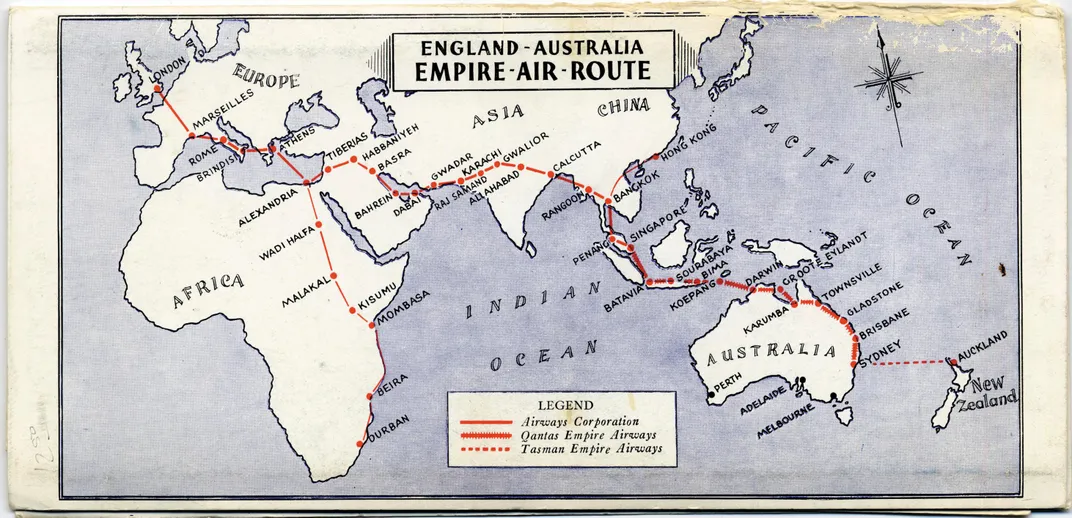

London to Sydney: 12,000 miles that started an airline.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5f/f3/5ff30c9f-5f1b-45e6-ab33-773a35ee6ebc/04e_aug2016_lanc800008_live.jpg)

The Avro Lancastrian VH-EAV bound for Auckland, New Zealand, was, on November 17, 1951, lined up for takeoff from Sydney Airport, Australia. Its destination was about seven hours’ flying time over the Tasman Sea, but the aircraft never made it. As it accelerated into its takeoff run, the Lancastrian veered to the left, its natural tendency. Following standard procedure, the captain applied right rudder as he advanced the throttles, with the number one engine leading, to compensate. Unfortunately, the number one engine failed. The ensuing accident report states that “corrective action by the captain failed to prevent the aircraft leaving the runway.” Seconds after VH-EAV departed the pavement, its landing gear collapsed, and it crashed in a shallow ditch, damaged beyond repair. Fortunately, the seven crew members escaped without injury. Airline employee John Brownjohn, who visited the scene the next morning, noted “that a man with a pot of paint and large brush had visited during the night, his task the customary obliteration of the name of the airline after a crash.” The name painted over: Qantas Empire Airways. Through a combination of Australian audacity and British protectionism, Qantas was operating what was then the longest airline route in the world, along which the now-ruined Lancastrian had played a vital role.

Operating the 12,000-mile trek from Sydney to London, known as the Kangaroo Route, was a logistical and engineering challenge eventually met only by modern jets. The Lancastrian was the airline’s interim solution. It had been extensively modified to carry spare Wright Cyclone engines for the U.S.-built Lockheed Constellations Qantas was operating on the route. Because of the length of the journey and the frequency of piston engine failures at the time, Qantas needed a way to get spare engines to each of the 16 airports between a flight’s origin and its destination.

A Not-So-Small World After All

Throughout the formative years of Qantas, all planning and policies centered on one reality: Australia’s geographical isolation from Europe. In 1919 the prime minister of Australia, William “Billy” Hughes, offered a prize of £10,000 to the first Australians to fly from London, England, to Darwin, Australia, in the hope this would lead to regular air service between the two countries. Six aircraft started the race in late 1919, but only two completed the journey. The winners, brothers Ross and Keith Smith, took 27 days; Ray Parer, in second place, took seven months. The results left no doubt that the challenges of the 12,000-mile distance were far beyond the capability of passenger-carrying aircraft at the time.

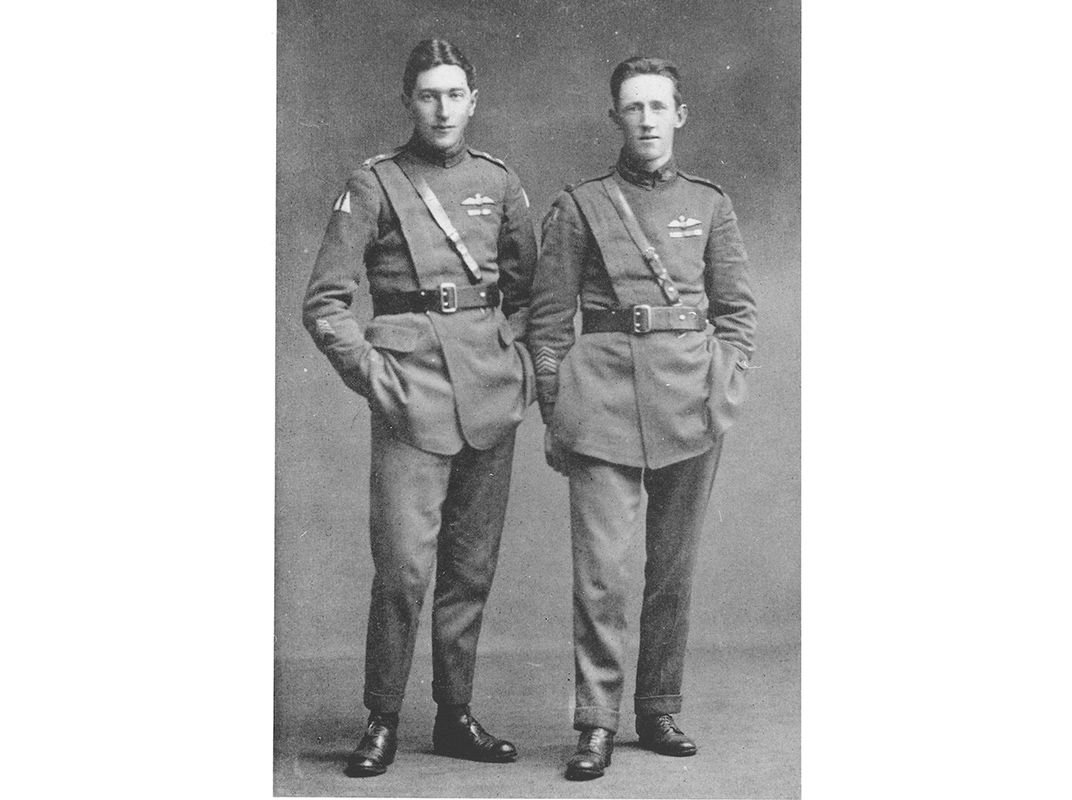

Two World War I veterans, Hudson Fysh and Paul McGinness, failed to attract sponsors to compete in the race, but were contracted to survey a shorter route: the one the competitors would follow once they reached northern Australia, over the vast states of Queensland and the Northern Territory. Fysh and McGinness traveled 1,300 miles in a Model T Ford, and became convinced that the widely scattered towns and cattle ranches would benefit from an air service for passengers and mail. They decided to start an airline connecting the two states.

Fysh, 25 years old in 1920, had worked as a cowboy on a sheep station before joining the army in 1914. By 1918 he was an observer in Bristol Fighters flown by McGinness; for their actions in the Middle East conflict, the pair were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. Despite a limited education, Fysh became an astute businessman who for 46 years navigated Qantas through negotiations with sometimes-hostile organizations and governments. (He was knighted in 1953 for his long service to Australian aviation.)

Fysh and McGinness teamed up with 42-year-old Fergus McMaster, who raised capital for the venture. Registered as Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Services, the name was later shortened to QANTAS. (Unaware that it is an acronym, generations have either misspelled it or wondered why it has no “u.”) McMaster served as chairman of the company for 27 years.

The first aircraft purchased was a two-passenger Avro 504K, and the first scheduled service departed November 1922. The passenger was 84-year-old Alexander Kennedy, an Outback pioneer who agreed to back the company with £250 provided he was given ticket number 1.

To keep their wood-and-fabric aircraft operating in remote areas, subjected to both extreme heat and monsoonal rains, and to coordinate spare parts delivery involving weeks of travel by ship from England, the company hired Arthur Baird, who had been McGinness and Fysh’s flight sergeant during the war. By the 1920s the airline had grown enough to require larger aircraft, and under Baird’s supervision, Qantas, still a small organization, accomplished an extraordinary feat: At the dusty airport in a small town 400 miles from the nearest city, Baird assembled the materials and know-how to build seven four-passenger de Havilland DH.50s, a relatively complex airplane.

Connection Made

By the 1930s, Qantas was an established airline in a position to expand into other ventures. An opportunity arrived in 1933 when the British and Australian governments agreed to set up airmail services in which British Imperial Airways would operate from England to Singapore, and an Australian company would operate from Singapore to Sydney. The formidable team of McMaster and Fysh submitted the successful bid, and the small inland airline was transformed into Qantas Empire Airways. It started operation to Singapore in 1934 with the de Havilland DH.86, a stylish four-engine, wood-and-fabric biplane.

That aircraft was soon obsolescent, however, and Qantas required carriers that were more modern. But the airline wouldn’t order the DC-3, which other airlines in Australia used. While the ban on U.S. commercial aircraft was lifted in 1936, says Qantas historian David Crotty, “the DC-3 was unsuitable for the long-haul U.K.-Australia route as there was a requirement to carry a large amount of mail as well as passengers. The flying boat was the only viable means of doing both in the absence of the larger landplanes and numerous large airfields that only appeared during and after World War II.” In 1937, Qantas replaced the DH.86 with the four-engine Short C class Empire flying boat, manufactured in Rochester, Kent, and operated it without loss until 1942, when the Japanese army invaded Singapore, severing the air route.

As World War II drew to an end, Fysh traveled to England to arrange resumption of direct flights between Australia and England. Qantas’ counterpart in the United Kingdom, British Overseas Airways Corporation, or BOAC (formerly Imperial Airways), announced it would introduce the Avro Tudor in 1947, followed by the Bristol Brabazon in 1950. In the meantime, it would use a fleet of Avro Lancastrians (converted Lancasters) and Hythe flying boats. Qantas was expected to follow suit. Facing an indeterminate period with obsolete aircraft, a dismayed Fysh wrote to chairman McMaster: “[S]erious consideration must be given to employment of American type aircraft and therefore wish to recommend acquisition of the Lockheed Constellation with 48 seats by day, convertible to 22 bunks at night.”

Qantas introduced Lancastrians and Hythe flying boats on the Kangaroo Route in 1946, but later that year ordered four 749 Constellations. BOAC continued its policy to buy British. Because the two carriers were operating “entirely different types, with different economics and passenger appeal,” Fysh recalled in his memoir Wings to the World, the boards decided that each would operate its own service between London and Sydney. Qantas would now operate all the way to London and carry the full burden of spares and equipment. That responsibility required a spare Wright Cyclone TC18BD engine to be available at each of the 16 airports between Sydney and London—a seemingly excessive number for just four aircraft, but Qantas would soon find that four more engines were urgently required.

The Constellations started flights to England in late 1947, and these quickly presented major problems: Engine failures occurred at airports as far as 50 flying hours from Sydney. The four-engine Constellation was soon branded “the best three-engine airliner in the world.”

Today we are used to the remarkable dependability of modern jet engines, so it is difficult to fathom the failure rate of the Constellation’s Wright Cyclones. Each aircraft averaged two to three failures per year. They were so common they received no publicity. The only consequence was accommodating passengers for a day while the engine was changed. Occasionally two engines would fail. Flight engineer Fred Burke recalled one such instance in 1954 in an oral history in the Qantas archives: “Number 2 engine failed before arrival at Singapore, the engine change delaying the aircraft for 24 hours. Shortly after take-off the next day number 4 engine failed and, during the shut-down drill, the propeller on the replacement engine went into overspeed, a dangerous condition which I addressed by shutting down that engine. There was no time to dump fuel, and in an overweight aircraft with only two engines running, my eyes were firmly focused on the sea wall right at the threshold of the runway, which had been impacted by a BOAC 749 not long before with heavy loss of life.” Qantas was then faced with four flights to transport engines: one to send an engine to replace the failed number 4, two to send the failed engines to Sydney, and one to restore a spare engine in Singapore. Each flight took 35 hours.

Since 1945, cargo and spare engines had been transported around the Qantas network by two Consolidated LB-30 Liberators, but by 1948 they were nearing the end of their lives. A replacement aircraft with suitable speed and range was required, preferably from within the fleet. Qantas’s Lancastrians were no longer being used for passenger flights, but the transport’s fuselage was too slim to accommodate an engine. The Lancastrian carried only nine passengers, facing sideways.

The senior engineer at Qantas devised a solution. Ron Yates, who had been a flight test engineer with the Royal Australian Air Force during World War II, reasoned that the ferried engine could be suspended from the normally sealed bomb bay, but this would require an aerodynamic fairing. With the aid of six draftsmen, Yates set about developing it.

The resulting structure was a semi-monocoque fairing about 21 feet long and six feet deep. The effect of the fairing on the flying qualities of the Lancastrian could be determined only by a test flight, however. The engineers feared the engine carrier modification would diminish the Lancastrian’s directional stability—the ability to resist sideslip, or yaw.

Construction of the fairing and the matching changes to the structure of the aircraft were accomplished completely within the Qantas workshops. With the large bulge beneath its fuselage, the aircraft became known as the Pregnant Lanc. Its test flight was made on May 17, 1949, commanded by Captain John “Minnie” Morton, a transport pilot who was senior training captain on Lancastrians. The remainder of the crew comprised a first officer, a radio operator, and Yates as observer. Arthur Lonegan, then a 17-year-old Qantas apprentice, vividly remembers the four-person crew wearing parachutes and lining up for a photograph (previous page) in which Yates displays cheery confidence, and the others appear more reflective. Many years later, First Officer Cec Zuber, a wartime Spitfire pilot, revealed that he was more apprehensive on this occasion than he had been before combat missions.

The flight would be impossible with the safety standards of today: The Australian airworthiness authority had sanctioned a major aerodynamic modification of a four-engine aircraft with uncertain effects on flight stability, and agreed to an experimental flight commanded by an airline captain, not a qualified test pilot.

The first flight was eventful, although the difficulties were in no way caused by the fairing. Morton lost airspeed indication, and then the radio failed. In a 1995 oral history, he said: “I carried out several circuits over the aerodrome as it was the only way to let the people below know we had problems. With almost two years of flying and instructing on the Lancastrian, landing without airspeed was not one of the procedures covered. On both sides of the runway, at intervals of about 200 yards, there were so many fire engines that we could not count them.”

As expected, directional stability was degraded. By experimenting during the one-hour test flight, the crew found that minor flap extension restored directional stability. Thereafter, the aircraft was always flown with a minimum flap setting fixed mechanically at 10 degrees. The other surprise was that the fairing reduced level speed by 2 to 3 knots and the fixed-flap setting by a further 7 to 8 knots.

After the two test flights, a Certificate of Airworthiness was granted. Registered VH-EAV, the Pregnant Lanc was assigned to flight crew training on May 23, 1949, and departed on its first mission on August 18, 1949, carrying a Cyclone engine to Karachi.

The Lanc’s Demise

All operators of the Lancastrian suffered an unfortunate level of accidents. Of the 54 Lancastrians operated by BOAC, British South American Airways, and Skyways, 14 were destroyed in accidents between 1946 and 1949. Nine were operated by Qantas, and these suffered eight accidents leading to either complete destruction or extensive structural damage. All but one accident occurred on takeoff or landing.

For pilots graduating from flying boats, for which virtually unlimited landing distances were available and approach speeds were much lower, landing a Lancastrian presented challenges. Every airport between Sydney and London was only 5,000 to 6,000 feet in length, and landings were purely visual, requiring critical judgment. The difficulty was compounded by inefficient braking and the absence of reverse thrust. A misjudged speed required a split-second decision to either go around or continue the landing with the risk of an overrun and a ground loop, and the final indignity of a landing gear collapse.

During its two-year career, the Pregnant Lanc made 32 “engine relief” round trips ferrying 64 engines; it carried a replacement engine to the location where a failure occurred, then carried the failed engine back to Sydney. The farthest journey was to Cairo, a round trip of at least 12 to 14 days.

The only time the Constellation’s engine failures received any publicity was in 1958, when the Queen Mother visited Australia. Qantas offered to fly her and her staff back to the United Kingdom via Africa on a Super Constellation. An engine and cowling were damaged at Mauritius, which caused almost four days’ delay as a spare was flown in from Perth. Another engine failed in Kampala, Uganda, causing a delay of 18 hours before the flight continued to Malta, where there was a third engine failure. At this point the Queen Mother reluctantly said goodbye to Qantas and returned to the United Kingdom on BOAC.

The Pregnant Lanc’s 1951 takeoff accident, on its final flight, was the third that particular Lancastrian had experienced. After seven previous accidents, the loss of VH-EAV was the last straw and undoubtedly hastened the departure of Lancastrians from the Australian airline industry. Qantas retired them all in 1952.

The Constellations remained in service until the late 1950s, when Qantas received its first Boeing 707. The jet cut flying time in half—traveling the Kangaroo Route in 57 hours rather than 103—without raising fares. After the loss of the Pregnant Lanc, engine transportation was taken over by Douglas C-54 Skymasters. Qantas would share the spare-engine burden with BOAC, which had finally made the previously unthinkable purchase of Constellations in 1949.

Today, nearly 20 airlines fly the Kangaroo Route, most making just one stop and averaging 22 hours flight time. But back in 1989, an aircraft made the long trip with no stops. When the first Qantas 747-400 was delivered to London, preparations were made for the first nonstop civil flight to Sydney. The 367-seat City of Canberra carried only 24 people and was stripped of all non-essentials in order to reduce the aircraft’s weight. The 747 set a new speed record when it touched down in Sydney just 20 hours, 9 minutes, and 5 seconds after leaving London.