Lunar mission in a bottle

Space historian Matthew Hersch writes in:On June 16, 1968, three astronauts left their homes in sunny Houston, and with little fanfare or press attention, quietly voyaged into space. They hadn’t been astronauts for very long: physician Joe Kerwin, selected in 1965, was the first of NASA’s new scien…

Space historian Matthew Hersch writes in:

On June 16, 1968, three astronauts left their homes in sunny Houston, and with little fanfare or press attention, quietly voyaged into space. They hadn’t been astronauts for very long: physician Joe Kerwin, selected in 1965, was the first of NASA’s new scientist-astronauts to command a crew; test pilot Vance Brand and X-15 rocket plane veteran Joe Engle had joined the astronaut corps in 1966.

Months earlier, a fire aboard a Block I Apollo spacecraft had killed its crew; now the new Block II Apollo had to be put through its paces before NASA could attempt a lunar flight. The three men were eager for the challenge despite the danger. None had ever been in orbit, but that did not matter to NASA: with other veteran spacemen training for the moon, the three rookies were the best men left for the job.

During their journey, Kerwin, Brand, and Engle lived only on the air and food they had brought with them as their spacecraft rotated slowly in the inky dark, protecting them from the vacuum and 200-degree temperatures outside. Exhausted and bearded, the men emerged from their vehicle seven days later, looking, as one recounted, “like hippies,” and donning sunglasses as their eyes readjusted to the light.

The astronauts, though, had never left Earth.

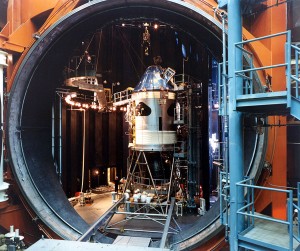

What sounds like the script for a Twilight Zone episode actually was one of several extraordinary dress rehearsals NASA conducted in the mid-1960s at the Space Environment Simulation Laboratory at Houston’s Manned Spacecraft Center (now the Johnson Space Center). A combination vacuum chamber, freezer, and oven capable of simulating the harsh conditions of Earth orbit and lunar flight, Chamber A of the Laboratory was so large that engineers could tuck a whole Apollo Command and Service Module inside it without scratching the ceiling (the door itself is 40 feet wide). Sealed in their spacecraft, Kerwin, Brand, and Engle experienced the dangers and discomforts of a lunar mission without ever leaving the test chamber.

The only aspect of spaceflight NASA couldn’t simulate on the ground was weightlessness, a detail that made these simulations even more difficult than the real thing. (An Apollo spacesuit alone weighed about 50 pounds in Earth gravity.) Still, the crewmembers were able to test Apollo’s hull and environmental control systems, verifying that the new spacecraft wouldn’t burst or burn when the Apollo 7 astronauts flew it into Earth orbit four months later.

The mission patch the crew designed for the test (designated 2TV-1), bore the image of a flightless road-runner and the motto Arrogans Avis Cauda Gravis: “The Proud Bird with the Heavy Tail.” The fact that the astronauts didn’t actually go anywhere, though, didn’t change the fact that they risked injury or even death during the tests. When a fuel line broke during another (unmanned) test of Apollo’s Lunar Module in July 1967, the ship was engulfed in flames. The following year, practicing an emergency exit from the LTA-8 Lunar Module test article, astronaut James Irwin accidentally cut off the flow of oxygen to his mask, passed out, and was prevented from falling down the steps by a rescue crew in the chamber. As Irwin later wrote, "Running these tests was almost like getting ready for a mission....You have to be very painstaking, because if you miss one step you've had it. You could hurt yourself and ruin the vehicle and zilch the timetable of the Apollo program."

See more photos from the 2TV-1 test here.

Hersch, an HSS/NASA Fellow in the History of Space Science at the University of Pennsylvania, is writing a labor history of American astronauts. He’ll be blogging regularly about the Apollo anniversary during the month of July.