What It Takes to Be a NASA Flight Director

Sitting in the hot seat at NASA’s Mission Control.

:focal(2004x453:2005x454)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/89/31/89314fb6-cc66-4647-8433-c82584d07d01/pauldye.jpg)

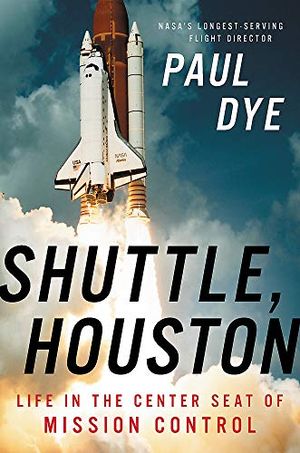

Paul Dye served as a NASA flight director from 1993 to 2013, overseeing dozens of space shuttle missions. The longest-serving flight director in NASA history, Dye has written Shuttle, Houston, a first-person account of how he orchestrated a sprawling team of flight controllers and systems specialists, all of them working in concert to provide a steady ground-based presence for astronauts orbiting above. Dye spoke with Air & Space senior associate editor Diane Tedeschi in December.

Air & Space: Why did you decide to write this book?

Dye: Well, Chris Kraft wrote his book about being a flight director during Mercury, and Gene Kranz wrote his about the view from the flight director console during Apollo. So I felt that someone should talk a bit about what it was like to fly the space shuttle program from Mission Control Center [at NASA Johnson]. The shuttle flew for 30 years, so there were quite a few stories to tell.

What abilities does a good flight director have?

A flight director needs to have well-developed leadership skills and be able to integrate across a wide variety of disciplines to plan and conduct space missions. They need to be good at multi-tasking, and have a very fast mind so that they can evaluate a large number of potential decision paths in a very short period of time in order to pick the best course of action. They also need to be able to submerge their ego in order to constantly listen to others and question pre-conceived notions—especially their own. And all of this is in addition to a deep and detailed knowledge of the spacecraft and space operations they are leading.

Did you and your team have a way to blow off steam after completing a long shift?

It was fairly common for those that wanted to get together to go to a local bar and have a few rounds of beers. The problem was that if you got off console at 2 a.m., there was no place to go. For a long time, folks would gather with a cooler in the parking lot out by the recreation center, but security didn’t like that. So they came up with a solution: At the request of the flight director, they’d open up the Saturn V display building and turn on the lights and air conditioning. Folks could stop in there and drink a beer under the Apollo command module. Honestly, it sometimes felt like drinking in church!

What did you learn from working with Gene Kranz?

I learned a lot from Gene, mostly by watching and listening to his leadership style. He is the embodiment of his slogan “tough and competent,” and you learn to be both while working with him. I think every flight director brings the ability to compartmentalize with them when they come to the office, but learning how to listen as well as command is something you learn from guys like Gene.

For those who work on crewed space-exploration programs, must they have an acceptance of risk?

Absolutely. To quote a line from the original Star Trek series: “Risk is our business.” You have to learn to analyze risks, develop mitigations for those you can, and then decide on a case by case basis which residual risks are worth taking to accomplish your mission. Space travel is risky, as are all high-energy activities. We have to take those risks to advance, and if you can’t do that, you can’t survive in this business.

Can you think of an engineering feat that rivals the space shuttle?

Well, building the International Space Station was pretty amazing engineering in and of itself: 30-plus missions to assemble, and all the major pieces fit together without a mission failure. But really, comparing engineering accomplishments across disciplines is difficult because there are so many challenges that have been tackled across human history, and each one was monumental when it was encountered. For its time, the shuttle was the most complex and high-energy transportation system ever built, and the sheer number of engineering challenges that were surmounted are almost uncountable. It was an incredible achievement, but so was going to the moon or—in the future—going to the moon to stay.

Do you agree with the decision to retire the shuttle in 2011?

If it were up to me, we’d still be flying the shuttle. The capability to bring back large masses from orbit is something that was unique, and something we don’t have today. Yes, flying the shuttle entailed risk, but so has every advance in human exploration across history. The [space shuttle] orbiters had lots of missions left in them—by design. I would have loved to continue supporting the International Space Station program and building up our space infrastructure to return to the moon—and beyond—using the shuttle.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.