The Greatest Test Pilot You’ve Never Heard Of

Meet Fitz Fulton.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Fitz-Fulton-631.jpg)

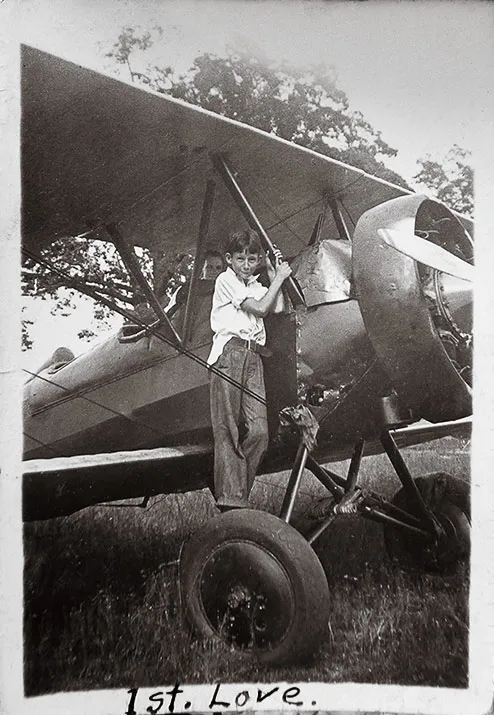

The photograph shows a boy of five or six, jug-eared and happy, holding on to the wing strut of a biplane. Taken in rural Blakely, Georgia, in the early 1930s, the image captures the joy afforded by small pleasures during hard times. But what boy would not be cheered by being close to a real, honest-to-goodness airplane? His mother evidently sensed the effect on her son, for she labeled the photo “1st. Love.”

The first of many. The boy would spend his working life in the close, sometimes perilous company of aircraft, taking them to war and exploring the extremes of their performance. His logbooks, with 17,000 or so hours of flight in more than 200 types, would tell the story of how aviation evolved from the 1940s onward. For this Georgia boy would be present at every crucial branching of that evolutionary path—from pistons to jets, subsonic to supersonic. He would fly everywhere and everything, all aircraft great and small.

Now 88, Fitzhugh L. Fulton Jr.—Fitz to family and friends—still has his mother’s photo. “I liked that photograph,” he says. “We protected it.” He thinks the airplane was a Kinner-powered Bird. He never flew in it. He got his first flight several years later, when a cousin sprang for a dollar ride in a Ford Tri-motor.

After his parents separated, Fulton and his two siblings moved with their mother to the larger Georgia town of Columbus, where, among other things, there was what he called a “real airport.” It had a 4,000-foot grass runway, and a fixed-base operation that flew J-3 Cubs and Taylorcrafts. In the time-honored way of air-minded youngsters, he began hanging out at the field, doing occasional chores and reaping occasional rides. Eventually, he settled into a more organized barter system: sweeping the hangar, washing and fueling the airplanes, pushing the airplanes in and out of the hangar—each was good for five minutes of flight, which he hoarded, then spent 20 minutes at a time. In June 1942, 17 years old, just out of high school, and not yet driving a car, he soloed in a J-3 Cub.

In 1943, with the U.S. armed services needing pilots to serve in World War II, he entered the U.S. Army Air Forces air cadet program. Fledgling pilots of movies and myth invariably opt for single-engine training, with an eye to becoming fighter aces. Fulton wanted to fly the twin-engine Lockheed P-38, though, so he chose multi-engine training. But when the P-38 failed to materialize, he followed the less glamorous road to transports and bombers.

It was one of those less traveled roads that would make all the difference. A career pilot of big airplanes, Fulton would fly the bombers that dropped the X-15 and other experimental speedsters at Edwards Air Force Base in California during the time now regarded as the golden age of flight test. And that experience led to opportunities in the space shuttle program. “I certainly welcomed the opportunity to drop the X-planes,” he says. Not, he quickly adds, that he was uniquely qualified. “Anybody could have flown the mother airplanes. But I had a lot of experience by then. I like to think I helped train some of the people.”

In 1945, his own training led him to Davis-Monthan Army Air Field in Tucson, Arizona. He reported for duty on August 14, but the officer checking him in the next day wondered why he’d bothered to show up. The war was over.

Although somewhat devoid of flight, the Tucson assignment had an unexpected reward. It was there that Fulton met Erma Beck, to whom he has now been married for almost 70 years.

Fulton was then sent to Roswell, New Mexico, where the 320th Troop Carrier Squadron was based. After winning a slot as copilot on Douglas C-54s, Fulton played a supporting role in Operation Crossroads, an atomic weapons project for which an armada of captured and surplus warships had been assembled in the lagoon of the Bikini atoll in the Marshall Islands. The first test, on July 1, 1946, would detonate a Fat Man plutonium bomb a few hundred feet above the lagoon to see what a 20-kiloton airburst would do to the ships and tethered animals below. A few weeks later, a second bomb would be detonated underwater.

For Fulton, Crossroads meant long hauls from Roswell to Kwajalein, the largest of the Marshall islands, ferrying the accoutrements of nuclear warfare. But the flight that stands out for him took place the day after the first bomb test, when he flew a C-54 carrying scientists and Air Force brass out to see what the bomb had done. Flying over the lagoon at about 200 feet, Fulton toured the affected area. It hadn’t occurred to him that the flight might expose him and his passengers to harmful levels of radiation. His attention was fully on the fleet of ruined warships.

In June 1948, in what became the opening political salvo in the cold war, the Soviets blockaded road, rail, and river access to the Allied-controlled sectors of Berlin, then a divided city. As the Allies mounted an impossibly difficult relief effort—the Berlin Airlift—Western aircrews with transport experience were suddenly very much in demand.

During central Europe’s formidable winter, Allied aircraft operated into and out of Rhein Main, Tempelhof, and Wiesbaden only a few minutes apart, undeterred by severe icing conditions, low ceilings, and zero visibility. Sometimes, Fulton remembers, you didn’t know you’d landed until you felt the tires on the runway. “It built up my confidence,” he says. “I’ve always considered myself a pretty strong instrument pilot. But weather was a big problem.”

When the airlift ended, Fulton headed back to the United States, this time to Eglin Air Force Base in Florida, where B-29s were testing new instruments. But the heat and humidity of Florida’s panhandle proved more than Ginger Fulton’s lungs could tolerate. Her asthma attacks got so bad Fulton and Erma feared they might lose their little girl.

A sympathetic commanding officer stepped in, and Fulton was offered a slot in southern California at what would soon be called Edwards Air Force Base. He didn’t know much about what went on there, but, certain that the change in climate would help his daughter, Fulton took the transfer. After settling in California’s high desert, Ginger’s health quickly improved.

Once jet-rated, Fulton began expanding his repertoire. In the early 1950s, borrowing an airplane was as easy as borrowing a Jeep from the motor pool. And when he wasn’t at the controls of a test aircraft, Fulton sat in as copilot or flew the chase aircraft.

Much of test piloting is the repetitive, rather humdrum stuff that makes its way into manuals as performance parameters—an airplane’s maxima and minima. Of course, nobody became a test pilot to generate data; they joined for the moments. One of those moments was a night flight Fulton made in a Lockheed F-94A, which, as he turned back toward Edwards, lost all electrical power, rendering the aircraft’s flaps, lights, and some critical instruments inoperable. Unable to set up a normal night landing, Fulton improvised. He stalled the airplane, which gave him a known airspeed, and from there worked out a letdown approach.

Asked today if that flight, or any flight, constituted a really bad moment for him, he says: “To me, troubles were opportunities. The best pilot in the world can get in trouble. I’m not a defeatist. I like to work on problems that are solvable.”

Barely two weeks into his term as a student in the test pilot school at Edwards, Fulton learned he was headed for Korea, where the conflict was entering its second year. Unlike some of the older test pilots, he had never flown in combat. On September 18, 1951, he arrived at K-8, the air base at Kunsan, South Korea. A day later, he began combat missions in the Douglas B-26 Invader.

His commander at Edwards had promised Fulton he would try to retrieve him when he finished his 55 missions in Korea, and the promise was kept. By May 1952, Fulton was back in test pilot school, which he completed that November. Not quite 27 years old, the unflappable, soft-spoken Air Force captain resumed his career as a pilot of all work.

He was soon shuttling between Edwards and the Convair plant in Fort Worth, Texas, to test-fly the company’s mammoth B-36. “My learning was rapid,” he wrote of the bomber in his autobiography, Father of the Mother Planes. “It had to be, because the B-36 was a high-maintenance airplane. We seldom completed a flight without having to shut down one or more engines. With rear-mounted propellers, engine oil leaking at high altitude would freeze and hit the props and then be thrown into the fuselage, sometimes even penetrating the airplane’s skin.”

After that, it was back to Edwards for bomb-drop tests from B-36s and tests of what now sounds like a harebrained scheme: a B-36 carrying an RF-84F Thunderflash, which would be deployed from and recovered on a retractable trapeze-like device extended from the bomber’s belly. The project was the first of many encounters Fulton would have with big ships carrying small ones.

He also began testing a new family of light jet bombers, among them the Glenn L. Martin Company’s XB-51. One of Fulton’s closest friends, Air Force Major Neil Lathrop, was killed during a low-altitude roll in the experimental aircraft. Fulton, flying a B-29 bomb drop test that day, saw the coil of black smoke rising from the dry lake. It was the first time Fulton lost a good friend to a new airplane; it would not be the last.

The Air Force had also become interested in the Royal Air Force’s English Electric Canberra twin-jet, which Martin was bringing out in the United States as the B-57. Fulton was assigned to the test flights.

On one B-57 flight, as he came out of a loop, he discovered that the control wheel had decoupled from the flight control system: Pushing the wheel full forward had no effect on the airplane. When things go wrong, some pilots yell on the radio. “That’s not my style,” says Fitz. “You have procedures. If you have a problem, then you call in and they offer suggestions.”

When Fulton reported the problem, the consensus on the ground was that he should bail out. But he thought if he used the elevator trim for pitch control, he might be able to save the airplane. He managed a fast, straight-in landing on the dry lake, for which he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

The B-57 would become his favorite airplane for traveling, and for several years he flew it in airshows.

The XB-52 and YB-52, the first prototypes of Boeing’s latest entry in the strategic bomber sweepstakes, were ready for testing in 1953, and Fulton was assigned to the project, which operated out of Moses Lake, Washington. Most of the time, he flew the F-86A pace airplane, to calibrate the new aircraft’s speed and altitude readings, or the chase aircraft. When the F-86 wasn’t needed, he flew on the bomber, and before long, he was checked out in the XB-52 itself.

The experience with the B-52 prototype would serve Fulton well in the years to come. Through the 1960s, the NB-52 was the airplane he flew with an X-15 or an experimental lifting body tucked under the bomber’s starboard wing. He flew the mothership for 92 of the 199 X-15 launches. In all, he was pilot for some 150 launches of manned aircraft.

The first age of the X-planes had begun at Edwards in the late 1940s, when the Air Force and what is now NASA began exploring the terra incognita of transonic and supersonic flight. B-29s and their descendants, B-50s, took off with small rocket-powered aircraft on their bellies. After release, the X-plane pilot lit the engine for a minutes-long powered flight to—and eventually well beyond—Mach 1. Then, on empty, the little ship, equipped with skids, would glide to a dry-lake landing.

Fulton was a natural choice for piloting the motherships. He flew as copilot on his first two X-1 drops, and as pilot on all his subsequent motherplane flights.

He flew the B-29s for the slightly larger and more powerful X-1A and B and the Douglas D-558-II Skyrocket. Fulton flew a B-50 for the Bell X-2, a hotter, swept-wing variant of the X-1. In September 1956, the new design made Fulton’s colleague Milburn “Mel” Apt the first man to fly faster than Mach 3. It was Apt’s first flight in a rocket-powered airplane—and his last. Tumbling out of control in a supersonic turn, the X-2 killed him. “It was a sad day for all of us,” wrote Fulton, “and that same high-speed instability later showed up on other new high-performance airplanes.”

The late 1940s was also the era of the Right Stuff, the term coined by author Tom Wolfe to describe the amalgam of courage, cockiness, patriotism, airmanship, and rowdiness required to be a test pilot. Fulton, although endowed with everything but the rowdy part—he drinks no alcohol, coffee, or tea—was not really conscious that this was going to become another of aviation’s golden ages. “I didn’t recognize it until later,” he says.

As for The Right Stuff, “everybody talked about it,” says Fulton, when the film was released in 1983. He saw the movie at the base theater. “It was good entertainment,” he says. “Everybody laughed.”

“The women didn’t like it,” says Erma, “because it made us look a little stupid.”

Fulton had another motive for keeping clear of the cowboy side of test piloting. “I was so appreciative of getting to fly airplanes…To me it was ‘Don’t tilt the boat.’ ”

By the mid-1950s, aircraft designers had turned toward the triangular delta wing, which, while presenting some challenges at lower speeds, offered to transform the dreaded sound barrier from a wall into a membrane through which aircraft could pass with barely a ripple.

In the United States, Convair was leading the trend. Overseas, the delta wing had made its way onto Britain’s Avro Vulcan and Vickers Valiant bombers, and the Anglo-French Concorde.

Fulton was sent to Boscombe Downs, the British counterpart to Edwards, to learn from Britain’s experience. He flew both the Valiant and the Vulcan, and, later, the Concorde. Accustomed to the almost weatherless Edwards sky, he was somewhat bemused by the British test pilots’ willingness to fly in any weather. His hosts explained that if they couldn’t fly their tests in English weather, they couldn’t fly their tests at all.

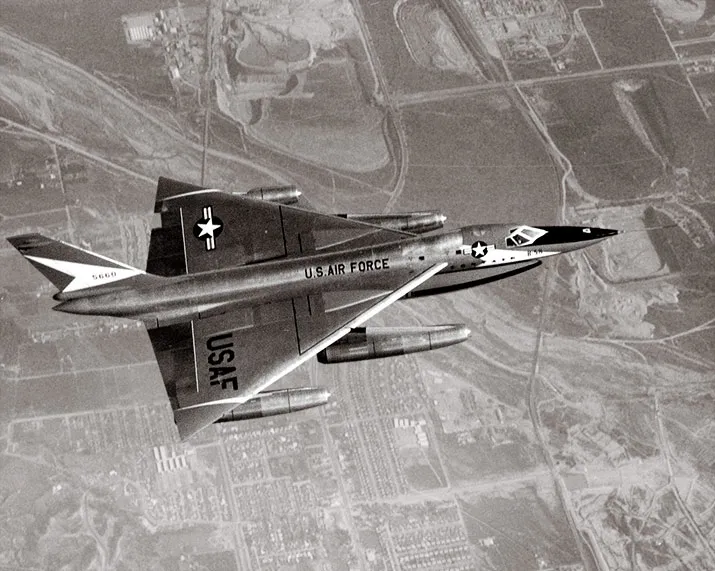

The quick trips to see Britain’s delta-wing bombers were, in fact, a prelude to Fulton’s next assignment. Down in Fort Worth, Convair was building the B-58 Hustler, a four-engine, delta-wing bomber with the speed and high-altitude performance of a supersonic fighter. Under the fuselage, it would carry a nuclear payload in a large streamlined pod. After it dropped its bomb and discarded the pod, it would come home “clean.”

The B-58 had its quirks. For one thing, there was a large amount of fuel to be wrangled. “You go supersonic, you have to move the fuel aft,” Fulton explains. “When you slow down, if you don’t move the fuel forward, you go unstable.” You spin. “Some would say there were bad moments,” he says. “But there were test pilots standing in line to fly the B-58.” A visiting general was the first Air Force pilot to fly the B-58; Fulton was the second.

Despite its idiosyncrasies, the Hustler would become Fulton’s all-time favorite. “It was super-fast for its time,” he says. “I was project pilot and helped shape the airplane.” And there was something else. “I have never considered myself as a true fighter pilot,” he explains. “But I do enjoy flying airplanes with only one seat.”

Eventually, Fulton became project pilot for the B-58 at Edwards; his responsibilities included evaluating the Hustler’s behavior when, near maximum gross weight, an engine was lost on takeoff. The tests involved accelerating to the “decision speed” and cutting one of the outboard engines. At or above that speed, the pilot must continue the takeoff, no matter what.

On one such test, Fulton had cut an outboard engine just before takeoff at 190 knots (218 mph) when the right main gear’s tires—all eight of them—began to disintegrate. Fulton felt nothing in the controls, but noticed rubber fragments spewing out on his right. He continued the takeoff, however, and, after a lookover by a fellow test pilot in an F-100, turned the hobbled B-58 toward home. “Landed at 100 knots,” he remembers, “not the usual 150. Pulled the nose up to slow it down and dropped the nose wheel for steering.”

In September 1962, Fulton flew a B-58 with a payload of 5,000 kilograms (slightly more than 11,000 pounds) to 85,364 feet, setting world records for both 2,000- and 5,000-kilogram payloads. For those flights, and his other work with the B-58, he received the international Harmon Trophy, naming him “the world’s outstanding aviator for 1962.” President Lyndon Johnson awarded him the trophy at the White House in September 1964. In his book, Fulton writes: “During the ceremony, I was standing right behind the President and could read his notes. It was all over so quickly. The Harmon Trophy is big and heavy but I carried it back to the hotel and onto our airplane for the trip back to California.”

That same month saw the first flight of North American Aviation’s XB-70 Valkyrie prototype, a Mach 3-plus strategic bomber intended as a successor to the B-52. Fulton flew chase in a B-58 while he and several colleagues spent a couple of years learning about the radical new bomber—an airplane, he says, that would be a close runner-up to the B-58 in his admiration.

Fulton had by then come to an important decision regarding his career. Offered a posting to the prestigious Air War College at Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama, he declined, fearing it would put him behind a desk. In April 1966, he filed his retirement request, effective at the end of June. Meanwhile, he continued flying the Valkyrie.

On June 8, 1966, Fulton was scheduled to fly the XB-70 in a test run that would segue into a calendar photo shoot for General Electric, showing a close formation of GE-powered aircraft: an F-4B, T-38, F-104N, F-5, and the number-two XB-70 prototype. But word came that a pilot was needed for an X-15 drop from the NB-52, and Fulton was reassigned. The X-15 drop was subsequently canceled, but it was too late to change the pilot roster for the XB-70. Major Carl Cross would pilot the XB-70, with Al White as copilot.

The Valkyrie completed its test program and settled into the photo session. For some 40 minutes, all went well. But then the F-104 drifted in toward the bomber, drawn, perhaps, by the XB-70’s wake vortex. The fighter bumped the larger airplane’s wing, then nosed up and, inverted, raked across the bomber, shearing off all of one vertical stabilizer and most of the other. The F-104 pilot was killed. Seconds later the Valkyrie rolled into a violent spin, losing part of one wing. Al White successfully ejected in his escape capsule. Carl Cross went down with the aircraft.

“I’ve always thought that if I’d been on the flight it wouldn’t have happened,” Fulton says, adding that it wasn’t his abilities that would have prevented the accident. “You change the players, you change the outcome.”

NASA wasn’t quite through with the Valkyrie; it wanted to use the remaining prototype in a high-speed flight research program with the Air Force. Fulton, now a retired Air Force lieutenant colonel, came to NASA with the airplane as primary project pilot, working with Donald Mallick, then a research pilot at NASA’s Edwards-based Dryden Flight Research Center. Like everyone in the test pilot community, Mallick had heard of Fulton, but this was the men’s first time working together.

Fulton and Colonel Joe Cotton, who’d been the primary Air Force pilot on the Valkyrie, began a checkout program for Mallick and Lieutenant Colonel Ted Sturmthall. “Flying the XB-70 was quite an experience for me,” says Mallick. “Fitz and Colonel Cotton were the [instructor] pilots. Ted and I flew with one of them on all test flights. A senior pilot and a junior pilot. I flew a total of nine flights. I was able to fly four of these flights from the left seat. I was proud that Fitz did not look on me as just a copilot. He shared the flying and testing.”

Fulton and Mallick would then fly something even hotter: the Lockheed Blackbird, in the form of the YF-12A and the YF-12C, which was actually the highly classified SR-71 in mufti. The pilots each made more than 100 flights in the Blackbird.

“Fitz and I alternated flights for almost 10 years, from 1970 to 1979,” says Mallick. “I always had the feeling that I was a better pilot because I was able to fly with him and share programs like the Blackbirds.” As the Blackbird research ended, they arranged an unforgettable going-away present for their comrades. Just before the last YF-12 was returned to the Air Force, they let each pilot in the office fly the Blackbird to Mach 3.

***

A key element in developing NASA’s space shuttle was finding a way to airlift the orbiter. NASA chose a stock 747-100. Named primary NASA project pilot, Fulton checked out in the 747. “I felt fully qualified but was surprised that so little time in the airplane was needed to make me legal to fly it,” Fulton writes in his book. All he needed was a 30-minute flight and one landing.

NASA 905, as the first shuttle carrier was called, was flown to Seattle for nine months of modifications at the Boeing factory. Its first flight with a shuttle was made in February 1977, with Enterprise attached to struts on the 747’s upper fuselage. A few months later, the seven explosive bolts tethering the shuttle were triggered, and Enterprise soared away on its historic glide to the Edwards runway. “The 747 had a strong pitch-down when the release occurred,” writes Fulton in his book. “I had to pull the control column aft with about 90 to 100 pounds of force. There was still a slight increase in the nose-down pitch trim. The indicated airspeed increased to approximately 320 knots for a few seconds. Just like a glider releasing from its towplane, the shuttle turned to the right after launch and we turned left.”

The shuttle-747 combos—NASA operated two of them—remained an amazing sight to the end, and never more so than on the final flight across the United States in 2012. By then, they’d taken many a star turn, not least the one at the 1983 Paris Air Show, where Fulton flew the motherplane with orbiter for the crowds every day.

Fulton retired from NASA in 1986, then spent three years as a test pilot for Burt Rutan’s Scaled Composites in Mojave, California. He and Erma live in Thousand Oaks, California, barely an hour’s drive from Edwards. Grounded by Parkinson’s disease, he misses having an airplane in his life. “I’d still be flying if I could pass the physical,” he says.

Although he flew transports and bombers throughout his career, Fulton never quite got over the glove-like fit of smaller aircraft. He owned a Fairchild 24 and, because he wanted a four-seater in which he could teach his family to fly, a Cessna 172.

His last airplane was a Meyer Little Toot homebuilt, a tiny biplane he saw after delivering the first shuttle to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. While technicians practiced loading the orbiter onto the carrier and unloading it, Fulton wandered off to a nearby airfield, where he saw the Little Toot. He thought it was a good-looking airplane that would be fun to fly. Back at Edwards, he and Erma decided to buy it. He returned and picked up the Little Toot for a five-day ferry back to California. The Georgia boy and his biplane.

Longtime contributor Carl Posey is a writer-of-all-work in Alexandria, Virginia.