Meeting Wilbur and Orville

To understand the brothers, one historian found that what you know is less important than who you know.

:focal(324x279:325x280)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/WrightBros.jpg)

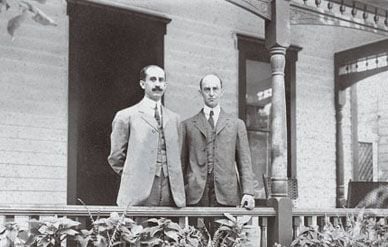

There was a (small) outcry when Orville didn't make The Art of Manliness’ list of “35 Manliest Mustaches of All Time.” The father of aviation lost out to a puppet—the Swedish Chef from "the Muppet Show"—and a cartoon character, Yosemite Sam. Courtesy NASM.

I HAVE DEVOTED THE BETTER PART OF 30 YEARS TO THE STUDY OF WILBUR AND ORVILLE WRIGHT and the invention of the airplane. I have written several books on the subject, and more articles than I care to count. I have no idea how many lectures I have given with titles like “Why Wilbur and Orville?” The producers of documentary films have enlisted me to serve as a “talking head,” describing the life and work of the famous brothers from Dayton. I have even appeared in an IMAX film, my head five stories tall, describing the Wrights’ achievement.

You might imagine that I would give almost anything to step back in time and join the four men and a boy who watched Wilbur and Orville Wright fly a powered airplane for the first time. You would be wrong. I would not find many surprises, standing around with my collar turned up against the wind blustering across the Kill Devil Hills on the morning of December 17, 1903. The Wright brothers kept a meticulous record of each of the four flights: times, distances, wind speeds. In later years they provided lucid and engaging accounts of their first powered flights. There are even photographs of three of the flights, including the famous one taken by John T. Daniels, one of the witnesses, at 10:35 a.m., just as Orville lifted the airplane off the ground for the first time.

Nor would I waste the opportunity to spend a few hours with Wilbur and Orville by choosing to witness any of the glider trials, which they conducted in 1900, 1901, 1902, and 1903. Thanks to my friend Rick Young, I have been there, and done that—or almost. Rick, a Virginia restaurateur, has built and flown replicas of the three gliders that were the Wright brothers’ stepping stones to success (see “The Thrill of Invention,” Apr./May 1998). All of this flying has been done in one place: Jockey’s Ridge, the largest single dune on the East Coast, four miles south of the Kill Devil Hills.

Today at the site of their experiments stands the Wright Brothers National Memorial, a wonderful place to visit. You can see full-scale models of the 1902 glider and the 1903 airplane, and Ranger Darrell Collins will describe the events of December 17, 1903, in a manner guaranteed to inspire you. You can peer into reconstructions of the two sheds in which the brothers lived and worked on this remote stretch of coast. Of course, you will want to hike up to the great monument on top of what was once the big Kill Devil Hill. Unfortunately, the creation of the monument required that the shifting sands so familiar to the Wrights be transformed into a very different landscape. Wilbur and Orville would no longer recognize the place.

They would feel right at home, however, on Jockey’s Ridge, now a North Carolina state park. Rick Young began flying his first 1902 replica from the ridge close to a quarter of a century ago. Fortunately, he invited me along on quite a few occasions. The flights have been reenactments in the truest sense. Civil War reenactors will always be thwarted in their desire to taste something of the life of the soldier. No one is shooting at them. Flying Rick Young’s gliders, on the other hand, one experiences precisely what the brothers did.

Thanks to Rick, I have felt Wright gliders come alive in the wind. Watching others on his team fly them is like seeing Wilbur and Orville’s wonderful glass plate negatives spring into motion and living color. It is one thing to sit in a library and read what the Wrights had to say about a problem with one of their machines. It is something else again to see that problem with your own eyes, standing ankle deep in the sand, puzzling over what just happened. Nor had it ever occurred to me how difficult it was to shlep those gliders back up the dune for the next flight until I had done it myself. The hours, days, and weeks that I have spent with Rick and his gliders have shaped, at the most fundamental level, what I think and say about the Wright brothers.

I first began to think about the Wrights in a serious way in 1970, when I was in graduate school. My timing was impeccable, for the scholars who laid the foundation for our understanding of the invention of the airplane and the early history of flight were still active. My mentors included Marvin W. “Mac” McFarland, chief of the science and technology division at the Library of Congress and the man who had edited the classic two-volume edition of The Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright.

I was sitting at a desk in the old Library of Congress manuscript reading room one day in the early 1970s when Mac walked up and handed me the address and telephone number of Ivonette Wright Miller. Until then, it had not occurred to me that the little girl with the blond curls peering impishly out of some of the Wright family photographs might still be living. Mrs. Miller was one of the Wright brothers’ nieces, born in 1896. Mac explained that the Library of Congress did not have all of the Wright papers. In 1948, library officials had taken only the most important items that the heirs of Orville Wright offered to them. Mrs. Miller and her husband, Harold “Scribze” Miller, still had a basement full of historical treasure.

I called Mrs. Miller the next time I was home visiting my parents in the Dayton area. She invited a young grad student whom she had never met into her home, and she turned me loose to dig through the boxes in her basement. There were priceless family papers: the diary that Wilbur and Orville’s father, Bishop Milton Wright, had kept for over half a century; family correspondence and genealogical records dating back to the early 19th century; the report cards and school papers of all the Wright children, including the inventors of the airplane; original photographs; box after box of financial records; and most of the Wright brothers’ library, complete with their handwritten notations on important aeronautical papers. I was only faintly aware of it at the time, but my career was born in that basement.

More important than all of that was the opportunity to sit at the kitchen table at the end of the day and have tea and cookies with a woman who could remember the day, just before Christmas, 1903, when Wilbur and Orville returned in triumph from Kitty Hawk. The inventors of the airplane were her babysitters. They had built and flown little helicopter models to entertain her. She had flown with her uncle Orville in 1911; been married in his Dayton home, Hawthorn Hill, seven years later; and served as his unofficial hostess for two decades. Her husband was one of the executors of Orville Wright’s estate.

While I was always conscious of the fact that Mrs. Miller had once lived right around the corner from her uncles, aunt, and grandfather, the reality of the thing occasionally came to me with stunning clarity. Working my way through a box of Wright papers at the Library of Congress one day, I came across a small notebook in which Orville Wright had kept the all-important record of their 1902 glider flights; on its pasteboard back cover, printed twice in childish block letters, was the name “Ivonette.” I immediately called Mrs. Miller and asked her about it. She remembered, as she always did. She had turned six that year, and had started school. Her uncle had asked her what she was learning. She replied that she could write her name. Come over here, he said, offering a knee, and show me. And now I held that long-ago signature in my hand. I knew the woman that little girl had become. To this day, it takes my breath away.

Her memories were a priceless gift, freely given. She offered me insight that I could have obtained in no other way. Sometimes understanding came at surprising moments. Once, when I was scheduled to come home to Dayton to give a talk at Wright State University, she called and suggested that this time, instead of staying with my parents, she would arrange for me to spend the night in Hawthorn Hill, now VIP quarters for the National Cash Register Company.

It was a wonderful experience. I got to sleep in Orville’s bed, bathe in his famous circular shower, and prowl his study, the only room in the house that remained as it had been at the time of his death in 1948. I pored over a scrapbook that I had never seen. I sat in his reading chair. He had drilled a vertical hole in one arm of an overstuffed chair and inserted the long pole of a music stand that he used to hold his book. There, on the side table, as though he had just stepped out of the room, were his reading glasses, with one temple removed so that he could put them on and take them off more efficiently.

Before the house was built, Orville had gone over every inch of the blueprints with the architect and made a great many changes. He had sketched details just the way he wanted them, including the way in which the carpet was to fit around the hearth. When the specially woven carpet arrived from Europe and did not fit, he sent it back.

Ivonette explained that when Orville lived here, there had been a cistern on the roof to collect rain water, which was piped through the back of the ice box so that he could have ice water constantly on tap. The only controls for the furnace were in his bedroom. He took great delight in the fact that he was the only one who could master the intricacies of the plumbing and electrical systems. Sitting there that evening, it occurred to me for the first time that this house had been Orville Wright’s machine for living. He had only really been comfortable in an environment that he had designed himself and which he could completely control. For a biographer, it was a defining moment, one of the many that I owed to Mrs. Miller.

She introduced me to other members of her family. I met her younger brother, Horace “Bus” Wright, and his wife Susan. In 1911, when he was 10, Bus traveled to Kitty Hawk with his uncle to test what proved to be the first glider in history to achieve soaring flight. On one of those flights Orville remained in the air for nine minutes and 45 seconds, a record that would stand for a decade.

I treasured a friendship with the late Wilkinson Wright, the son of Ivonette’s older brother Milton. When he was a young man in the 1930s, “Wick” and his cousins had spent summers with Orville at his vacation home on an island in Canada’s Georgian Bay. As he told it, however, there was little vacationing going on. “Uncle Orv” kept his grandnephews busy shifting the location of buildings on the island, building a “junction railroad” to bring luggage up from the beach to cabins on the bluff, and performing general chores.

The opportunity to know members of the Wright family, their wives, children, and grandchildren, has been one of the great pleasures of my professional life. It occurred to me many years ago that I knew far more about their family than I did about my own. Relatives further back than my grandparents are only names to me, or unfamiliar faces in fading photographs. I can, on the other hand, recite from memory much of the Wright lineage back to the 17th century. I can tell you something about the personalities of family members, including the two Wright brothers you never hear mentioned—Ivonette’s dad, Lorin, and first-born Reuchlin. I can tell you how they lived and died, their triumphs and disasters. I have read the letters and diaries of generations of Wrights. I am certain that Orville Wright, that most private of men, would be very unhappy knowing how familiar I am with his inner life and that of the other members of his family. He did what he could to discourage would-be biographers. I find it hard to believe that he would accept anyone as nosy as I am.

For all of that, I would know more. Several years ago one of my favorites of the present generation of the Wright family introduced me to an audience as “our family Boswell.” I could not have been more proud. At the same time, I have had none of the advantages James Boswell had in spending years in the constant company of the writer Samuel Johnson. He traveled with him, discussed everything under the sun, met his friends and family. I would be happy just to spend an afternoon in the company of Wilbur and Orville.

As noted, I would not choose a time when they were preoccupied with their experiments. Rather, I would stroll into the Wright Cycle shop at 1127 West Third Street in Dayton, Ohio, on any afternoon in early August 1899. Just three months before, the brothers had announced their interest in flight for the first time in a letter to the Smithsonian Institution requesting information on the state of the aeronautical arts. Recognizing that other pioneers had built wings that would lift them into the air, and that propulsion was an issue that could wait, they quickly decided to focus on aeronautical control.

Standing in this very shop that spring, idly fingering a long, narrow box that had contained an inner tube, Wilbur had come upon the notion of moving the top wing of a biplane fore or aft of the bottom wing, and even inducing a helical twist across both wings in a way that would enable a pilot to control the movement of the center of pressure on the wing, and thus the motion of a flying machine. He built a small skeletal model of such a biplane out of bamboo slivers, rigged with thread, just to clarify in his mind the mechanics of the thing. Then he built a biplane kite with a five-foot wingspan to test the principle.

He walked out of the bike shop one day late in July with the kite carefully tucked under his arm. He walked four or five blocks west on Third Street, then turned north for two blocks. Along the way, he collected a crowd of boys who had abandoned their own kite flying activities to follow Wilbur. Arriving at an open field at the corner of West First Street and Euclid Avenue, near the Union Theological Seminary, he set up the kite and unwound the four 20-foot lines that would control its motion.

Wilbur asked one of the boys, Johnny Myers, to hold the kite as far above his head as he could and to let it go when instructed. “There was quite a big wind that day,” Myers reported many years later. “I recall that when he tilted the planes, the kite came down very rapidly.” With a bit of practice, Wilbur was able to maneuver the kite in the air. It was a tricky business, however. Once, when he allowed the lines to go slack, the kite darted toward the ground, scattering the young onlookers. On that quiet summer afternoon, Wilbur Wright had taken the first step toward the invention of the airplane.

I have a kite like that. A friend who is far better with his hands than I am built it for me. It is not easy to fly. Without some weight in front of the leading edge, I can’t keep it in the air at all. For a long time, my record duration aloft was 20 seconds. My kite, and all of the other replicas that people have built, are based on a simple drawing that Wilbur sketched one morning before testifying in a patent suit. I would like to see what his kite was really like. And I would like to ask how long he really kept it in the air on that first day. Maybe he could give me a few tips.

I would not choose to visit on the day he flew the kite, because Orville was away on a camping trip, and I would want to meet them both. I would like to shake hands with the brothers, long before they tasted fame, at a time when the possibility of actually succeeding where so many others had failed was the most distant dream.

I would like to hear their voices. No recording of either of them has survived. I know what others have said about their personalities. Members of their family have described them to me at length. I have read what they wrote, and drawn my own conclusions. I would simply like a reality check on my assumptions about these two men, to whom I have given so much thought.

I would like to walk home with them, to the house at No. 7 Hawthorne Street. What would I not give for the opportunity to chat for a few minutes with their father, Bishop Milton Wright, the man who was so important in shaping the lives of his children and through them the history of the 20th century? I would certainly not pass up the chance to spend at least a few minutes with their sister, Katharine. And I would want to walk the neighborhood, getting a feel for the few blocks along West Third Street that the Wrights knew so well.

Of one thing you can be certain. My visit to the West Dayton of 1899 would not be complete without a walk around the block to Horace Street and a visit with a three-year-old charmer named Ivonette. For my money, that would be an afternoon in the past well spent.