Midnight Raiders

How zeppelin bombers during World War I terrorized the British-and their own German crews.

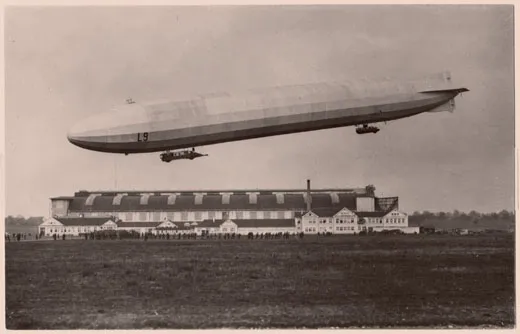

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1a/b4/1ab4aba7-2bdc-4946-92bf-fad44526be72/07d_on05.jpg)

LONDON, MAY 31, 1915. The moon has set and a cold north wind brings the promise of heavy weather. It’s a night to seek shelter, yet hundreds of people made bold by curiosity have spilled into the streets or found a rooftop perch. They speak in whispers or silently gaze up into the darkness, ears cocked to pick up the distant drone of engines, which has already been reported by listening posts on the east coast of England.

A searchlight beam pierces the sky and is instantly joined by several others, all warping into odd angles where they’re blocked by clouds. For a fleeting second, one of the beams touches the underside of a silvery, cigar-shaped object. The beam slides past, then snaps back. The rest quickly converge on the spot, their white tips locking onto the ghostly intruder.

With the airship exposed, the big guns of anti-aircraft batteries ringing London go into action. Flashes light the horizon and booming sounds shatter the silence. The response—from German Zeppelin no. LZ38, a million-cubic-foot airship under the command of Hauptmann Erich Linnarz—isn’t long in coming. The crew begins dropping 3,000 pounds of conventional and incendiary bombs, their dull thuds followed by explosions that make the ground tremble, setting fires and collapsing buildings. Shrapnel from the anti-aircraft shells rains down, pelting buildings and pedestrians and adding to the pandemonium.

The aerial assault by a lone zeppelin raider that night in 1915 was the first in a series of attacks on London, launched to crush England’s will to fight during World War I. Londoners had no doubt read newspaper accounts of earlier raids that had set nerves on edge in coastal towns, beginning with Great Yarmouth, on the Norfolk coast, on January 19, 1915. But those attacks were intended for naval bases, docks, troop camps, and factories making war goods. The London raid had a different psychological impact. Although property damage was minimal and only seven people were killed, the English now knew they could no longer count on the sea surrounding their kingdom or on their powerful navy to protect against attack. Even the heart of the empire, hundreds of miles from the frontlines, lay exposed to the horrors of war.

Well before the August 1914 beginning of combat, as both sides cranked up their military machines, the German navy had been building a fleet of large, advanced airships—referred to as zeppelins after their creator, Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, a career army officer who had been advocating the use of lighter-than-air craft since the 1890s. Despite the count’s plan that the airships be used “for the observation of hostile fleets and armies but not for active participation in actual combat,” the German military routinely boasted about the zeppelins’ range and bomb-carrying capacity. To accommodate the growing fleet, Germany constructed more than a dozen large bases, mostly on the North Sea coast, each with revolving hangars so the airships could be pointed into the wind at launch.

When war finally broke out, the question was not whether but how soon Germany would unleash its new weapon on England. The emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, at first resisted aerial bombing for humanitarian reasons. But he finally agreed, with the stipulation that Westminster Abbey, St. Paul’s Cathedral, the Houses of Parliament, and royal palaces were off limits—Wilhelm was, after all, related to the British royal family.

What had helped change his mind were the heavy losses in the trenches of the Western front and the “hunger blockade” of German ports by the superior British navy. Peter Strasser, the energetic and discipline-minded commander of the Naval Airship Division, argued to his superiors that “England can be overcome by means of airships, inasmuch as the country will be deprived of the means of existence through destruction of cities, factory complexes, dockyards, harbours and railroads.” The raids, Strasser hoped, would force the British to shift troops and guns from France to protect their homeland, and would demoralize soldiers at the front when they learned their families were suffering under the fury of aerial attack.

Moonless nights were ideal for the raids, since the defenders could not spot zeppelins approaching in the darkness. Raiders lifted off from seaside bases in early afternoon, crossed the English coast at dusk, arrived over their targets around midnight, attacked, and headed for home before daybreak. Since the airships’ navigational devices were primitive, the crews relied on railroad tracks, the glow of city lights, or the soft sheen of rivers and lakes to guide them to their targets.

Weather was the wild card. Cloud cover made navigation a nightmare, and unexpected storms could damage airships or cause them to drift off course. Strasser responded by building a string of meteorological stations along the German coast. While weather predictions were generally accurate for lower altitudes, upper atmosphere forecasts were useless.

“Leaving England forty minutes after we had started the bombing,” Captain Ernst Lehmann recalled in his 1927 book The Zeppelins, “we ran into another heavy snow squall, and the wind became a hurricane. At one time it gripped the L11 and bore her straight up 3,000 feet. When she settled back again, the tail steering fins were jammed. Before we could balance the craft she again was tossed up for more than half a mile. Finally we got our ship on an even keel by shifting the crew back and forth in the gondola, and held her there until the damage was repaired.”

The first raiders flew at an altitude between 3,000 and 8,000 feet—out of range of anti-aircraft guns and safe from the fragile and underpowered British fighters, like the Royal Aircraft Factory BE2c that rose to challenge them. Once over their target, the zeppelin crews dropped parachute flares to blind the gunners below, or ducked into a cloud or fog bank to hide from their pursuers.

Flying a zeppelin was more like sailing a ship than piloting an airplane. The captain stood, binoculars around his neck, with the watch officer and control surface operators in a small (seven- by nine-foot) forward gondola, also known as the command gondola, slung underneath the hull. There they maintained the ship’s altitude and course with two nautical-style steering wheels. The captain gave orders through an intercom-like speaker tube to mechanics in the engine gondolas as well as to crewmen manning the bombs and ballast or to lookouts and machine gunners atop the ship. Another pair of gondolas housed the massive diesel engines that powered the airship to speeds as high as 50 mph.

Zeppelins weren’t simply balloons filled with gas; they had a rigid frame. The inside of the 650-foot-long hull was a gargantuan cage of duralumin girders and steel wires housing up to 19 hydrogen cells. Catwalks along the skeleton allowed 16 to 20 crew members to move through the ship, and a vertical ladder gave access to the outside through the top of the hull. Those not on duty could rest in hammocks slung along a gangway inside the hull between the forward and rear gondolas.

For the zeppelin crews, exhilaration and fear went hand in hand. Recalling a 1915 bombing run over London in a magazine article published 13 years later, Lieutenant Commander Joachim Breithaupt described flying high above the darkened city as he followed the windings of the Thames River to his target: “We watched the beams of the searchlights slashing into the sky like unsheathed swords looking for our airship…. The ship rocked when a round came close and shrapnel filled the sky. How could the enemy fail to hit the huge target that was my airship? One hit from the incendiary shells and they would go up in flames with no chance of escape. No zeppelin carried parachutes, for it had been decided every extra ounce of payload would be given to bombs.”

While Breithaupt found the scene “indescribably beautiful—shrapnel bursting all around…and the flashes from the antiaircraft batteries below,” he couldn’t help remembering a sister zeppelin bursting into flames after being hit by enemy fire. As that ship fell to Earth, it was engulfed in a sickening glow for three agonizing minutes, its crew burning alive.

Nor was the destruction one-sided. Moments after he released his bombs, Breithaupt could see pools of fire and smoke on the ground below. The bombs had hit, but where? He knew aerial bombing was far from precise, and that many of his bombs would likely miss their military or industrial targets, hitting homes and innocent people instead. In fact, he learned later, the bombs had fallen on London’s theater district, where they started fires from shattered gas mains and killed a number of civilians.

When the zeppelins first appeared over English skies, the British countered by setting up listening posts and observers along the coast and on patrol ships to pick up the sound of airship engines. Anti-aircraft gun and searchlight batteries were placed around target cities. And fighter squadrons based in northern France made a series of daring raids on the few German airship bases they could reach in occupied Belgium.

The zeppelins’ Achilles’ heel was the hydrogen that gave them lift, which could easily be set ablaze by incendiary shells or even bullets. Early in the war the airships generally flew too high for Allied airplanes to reach, but luck or resourcefulness sometimes helped the defenders. On June 17, 1915, Royal Flying Corps Sub-Lieutenant Reginald Warneford spotted LZ37—one of the few zeppelins owned by Germany’s army instead of its navy—while flying his Morane-Saulnier L low near the Belgian coast. His account of what ensued is in the Imperial War Museum in London: “I arrived at close quarters with the zeppelin a few miles past Bruges, and the airship opened heavy machine gun fire, so I retreated to gain height and the airship turned and followed me. I came behind, but well above the zeppelin, and then slowed to descend on top. At 7,000 feet, I dropped my bombs, and, whilst releasing the last, there was an explosion which lifted my machine and turned it over. I went into a nose dive and regained control. Then I saw the zeppelin on the ground in flames.” Warneford received the Victoria Cross for being the first pilot to down an enemy airship.

The British raced to improve both airplanes and guns. By early 1916 they had replaced their anti-aircraft batteries with more accurate French guns, and began deploying new fighters like the de Havilland DH2 and the Sopwith Camel with ceilings matching those of the airships. More important, pursuit aircraft began firing phosphorus incendiaries, called “flaming bullets,” which caused so much grief to zeppelin crews that the Germans called them “the invention of the devil.”

The improved defenses were tested in September, when the Germans attacked with an armada of 16 airships, the largest fleet ever sent against England. The early warning system along the coast gave Lieutenant William Leefe Robinson of the Royal Flying Corps time to scramble his new single-seat BE2c fighter. It took an hour to climb to the zeppelin’s cruising altitude over London; the city was blacked out, the only illumination coming from searchlights. The higher Robinson climbed, the more numbing the cold in the open cockpit. For protection, the pilot had only his heavy flying suit and gloves.

At 12,000 feet over the Thames, Robinson spotted the distinctive shape of an airship caught in the beam of a searchlight. Before he could maneuver into range, the zeppelin saw him and disappeared into a cloud. Pushing his single-engine biplane to the limit, Robinson climbed to 14,000 feet and resumed a zigzag search pattern. At 1:30 a.m., his fuel tank nearly empty, Robinson began thinking about the dangerous night landing he faced on a fog-bound field, when the glow of explosions on the ground a few miles northeast caught his eye. It could mean only one thing: German bombs hitting their targets. The zeppelin that had dropped them couldn’t be far away, so Robinson headed straight for the explosions.

By the time he was over the area, searchlights were combing the sky and he could see anti-aircraft shells bursting below him. There, its nose sticking out of a cloud, was the cigar-shaped gasbag of SL11.

Robinson dove to gain speed. “I flew along about 800 feet below it,” he reported on his return to base, “at an angle that blocked the view of the defenders, and fired one drum from my Lewis gun without effect. I moved to one side and gave it another drum, again with no effect.” The zeppelin turned away and began climbing. The crew had seen Robinson, and machine gunners on the top of the airship and in the engine gondola soon began firing back. Tracers came his way, but they were off the mark. “By this time I was close, 500 feet or less below. I aimed underneath the rear and emptied the remaining drum.”

The sky suddenly turned bright as day, and Robinson’s airplane began to wobble and turn in a sea of incandescence. As he struggled to regain control, narrowly avoiding the fireball, the zeppelin’s metal frame broke, and the pieces plummeted to earth, while men jumped from the airship to avoid being burned alive. Robinson was so elated by his victory he fired his Very pistol and dropped a parachute flare.

The downing of SL11 boosted British morale. The citizens held celebrations and rang church bells. For the German commanders, the loss prompted an all-out effort to counter airplanes that could now match their zeppelins’ altitude. By August 1917, Strasser leapfrogged ahead of the British with redesigned “height climbers.” The new airships were 700 feet long and 10 stories high, and due to lighter materials, a reduced bomb load, and even fewer amenities for the crew, they could reach more than 20,000 feet. For protection, the zeppelins carried 10 machine guns, four tons of bombs, and a new, more accurate bombsight.

The crews of the height climbers paid a heavy price for safety, however; the higher cruising altitudes were near the limit of human endurance. Oxygen deprivation caused dizziness and nausea in the gondolas, and in remote areas of the airship, men who lost consciousness risked death. Gloves were essential—those who touched the ultra-cold metal with their bare hands would leave their skin on it.

Even by World War I standards, zeppelin duty was a miserable assignment. Otto Mieth, watch officer aboard airship L48, wrote in his memoir that at 15,000 feet, “We shivered even in our heavy clothing and we breathed with such difficulty in spite of our oxygen flasks that several members of the crew became unconscious.” As soon as the ship dropped its bombs on Harwich, 20 or 30 searchlights converged on the intruder. Guns fired from the ground, and in an instant the ship was ablaze. “I heard the man next to me say, ‘It’s all over,’ and I sprang to one of the side windows to jump out, the thought of being burned alive was so horrible,” Mieth recalled.

“At that moment the ship’s skeleton collapsed, the gondola swung over and I fell into a corner with others piling on top of me. I felt flames against my face and I wrapped my arms against my head, hoping the end would come quickly. That was the last I remember.” When the ship’s metal frame hit the ground it telescoped, breaking the fall. Mieth surmised afterward that the pile of comrades on top of him had shielded him from the flames. English soldiers heard his groans and pulled him from the wreckage—he was one of the very few men to survive the downing of a zeppelin.

Despite the losses, the raids continued. In October 1917 Strasser launched 11 height climbers in a massive attack. As they descended to a lower altitude on their return trip, half the zeppelins were destroyed by French and British fighters. Three months later five airships exploded in their hangars at Ahlhorn, Germany. Sabotage was suspected, but the cause was never established.

By this time, it was obvious even to their staunchest defenders that the airships were having little success. In late 1916 the German command had begun air assaults with twin-engine Gotha bombers, which had speed, range, and bomb loads that nearly matched the zeppelins’. In a single raid in June 1917, 23 Gothas did more damage than all the zeppelin raids combined.

The zeppelins still posed a threat, however, so the British decided to take the fight to their North Sea bases. The first target chosen was Tondern, near the Danish border in northern Germany. Tondern was beyond the range of Allied bombers launched from England, but the British solved the problem by taking the cruiser HMS Furious and replacing its superstructure with a deck, thus transforming the ship into an aircraft carrier.

Escorted by several smaller ships, Furious left Britain on July 18, 1918, carrying seven Sopwith Camels. At dawn the next day, the squadron led by Captain B.A. Smart took off for the German coast, 90 miles away. The attackers followed roads to the base, dove from 5,000 feet, and dropped their bombs on the huge hangar, destroying two zeppelins inside. The Tondern raid was the first successful attack ever launched from an aircraft carrier.

In August 1918, Strasser, ever the optimist, introduced yet another airship advancement. The L70 was a long-range, six-engine giant that could cross the Atlantic, drop an 8,000-pound load of bombs on New York City, and return to base without refueling. The Americans had recently joined the Allies, and Strasser hoped that such a raid would shock the Americans, knocking them out of the war. Before taking such a bold gamble, though, the commander decided to try out the L70 himself on a raid over England. He had already escaped death twice and won Germany’s Iron Cross for bravery. The high command attempted to dissuade him, but Strasser would not be turned back.

Joined by four other airships, the L70 took off on August 5, just three months before the end of the war. To improve accuracy, Strasser decided to approach the target at low altitude, drop his bombs, then ascend to maximum height and be gone before the British could react. But the accompanying airships were picked up by coastal listening posts, and a swarm of British fighters were scrambled to meet them.

One of the swift, new de Havilland DH4 two-seaters, with Major Egbert Cadbury piloting and Captain R. J. Leckie in the gunner’s seat, climbed unobserved and approached Strasser’s ship. As Cadbury made his pass, Leckie fired bursts of incendiaries from close range. Flames spread along the hull, first toward the tail, then toward the bow. In less than a minute the airship, along with its crew, plunged to the ground in a mass of burning fabric and twisting metal. Strasser met his death in the last zeppelin raid of the war, and with him perished the German Naval Airship Division.

All in all, zeppelins fared badly in World War I. Of 123 airships that the German navy and the army flew during the war, 79 were destroyed by enemy action, weather, or accidents. Forty percent of zeppelin crew members, most of them volunteers, were killed in action—exceeding the percentage of losses suffered even by the U-boat service.

And for all the drama of the zeppelin raids, they did little to influence the outcome of the war. In 57 raids on England, the airships dropped an estimated 220 tons of bombs, causing $10 million in damage, injuring 1,500 people, and killing about 600 (of the nearly 10 million killed in the war). The raids did succeed in tying down more than 20,000 British soldiers and diverting guns and military airplanes from the front. They also caused blackouts that disrupted war plant production.

But the airships’ greatest effect was probably on British morale, particularly early in the war. Even though the English came to realize the zeppelins were less of a threat than they had seemed, the raids had psychological consequences. “The scars of World War I air raids were never healed in the British mind,” wrote Hanson Baldwin, a respected military analyst for the New York Times, half a century later. “Peoples’ thoughts instinctively fly upwards,” wrote British historian Liddell Hart. The zeppelin raids and lesser known attacks by Gotha bombers had made an indelible impression in the collective mind, according to Hart. ”The tendency, whenever they think of war, is for the thought to be associated with the idea of being bombed from the air.”

At the beginning of the next European war, Luftwaffe head Hermann Göring would play on these fears, boastfully threatening in 1939, “Once again as the German zeppelins did 25 years ago, German squadrons will unleash air raid alarms over London. The German Air Force will strike at Britain with an onslaught such as has never been known in the history of the world.”

So Strasser’s vision survived, even if the technology didn’t. In the 1920s and 1930s, zeppelins were used only as passenger ships, the Graf Zeppelin and Hindenburg being among the most famous. But the goal of demoralizing an enemy from the air remained the same—whether from zeppelins or buzz-bombs or B-29s—as the citizens of London, Dresden, Tokyo, and Hiroshima would find out all too soon.