Mission to Enceladus

NASA summer students plot a course for Saturn’s mysterious ice world.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/enceladus-388-sept06.jpg)

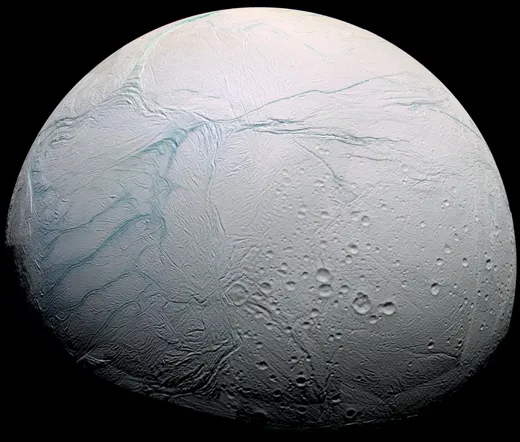

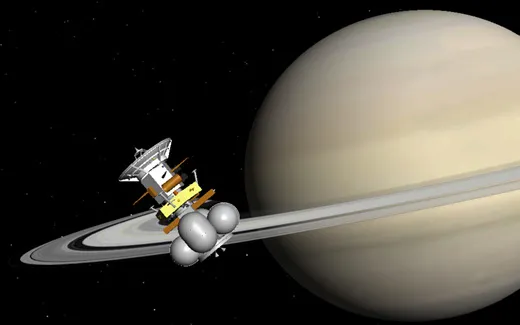

Out in the far reaches of the solar system, things are mostly cold, dull, and dead. That’s why scientists sat up at their computers last year when pictures returning from the Cassini spacecraft showed enormous geysers of water erupting from the warm south pole of Saturn’s moon Enceladus. What’s more, Cassini’s instruments detected organic compunds like methane in the spray. Water plus warmth plus organics equals the possibility of life, and Enceladus immediately shot to the top of the list of most intriguing places in the solar system.

James Wray followed the news with more than usual interest. Having majored in astrophysics at Princeton, he hopes to make a career in the space program. So when he arrived at Maryland’s Goddard Space Flight Center in June for this year’s NASA Academy—a summer study program for top college graduate students and undergrads—he was already toying with an idea: a spacecraft mission to explore Enceladus.

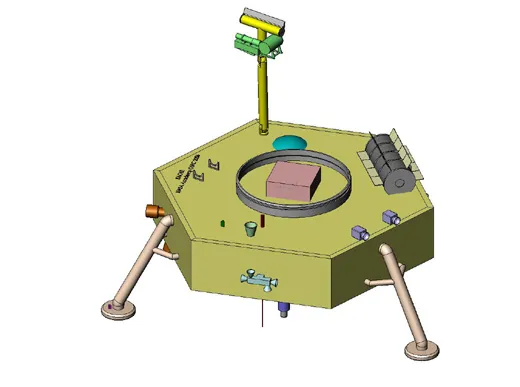

Last week Wray and his fellow Academy students delivered the final presentation for their eight-week group project based on Wray’s suggestion: the NASA currently has no plans for another Saturn probe, the EAGLE proposal gives hope that someone, someday, may launch something very much like it.

The Academy students—20 of them, all engineering and science majors—picked June 2023 as the date of departure from Earth. Seven years later, after swings past Venus and Earth to gain speed, the combination orbiter-lander would arrive at Enceladus. (The team considered just an orbiter, says Wray, “but we decided that was too boring.”) To ground their design in reality, the students outfitted EAGLE with instruments used on actual missions, including cameras from NASA’s Spirit and Opportunity Mars rovers, an amino acid analyzer from the planned European ExoMars mission, and a sample analyzer (EAGLE would drill a sample from the icy crust) based on one that will fly on NASA’s upcoming Mars Science Laboratory. The students even took a stab at estimating the price tag: $838 million, or $1.13 billion if you throw in the cost of launch and operations. The payoff would be determining whether liquid water—and maybe life—exists today on Enceladus.

The college students may have beaten the professionals to designing a mission, but planetary scientists have already begun thinking about a return to Enceladus after Cassini. NASA’s Outer Planets Assessment Group, which advises the agency on strategies for exploring the solar system beyond Mars, took up the subject of future Enceladus missions at American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences meeting in Pasadena, California in October. Wray and two other members of the EAGLE team plan to present their results at the meeting, and most of the 20 students from this year’s Academy will be there.

Until recently, Jupiter’s moon Europa was the preferred target for future exploration in the outer solar system, because of the ocean thought to lie beneath its crust. But the icy shell around Enceladus is likely much thinner, at least in some places. The reservoir of water that feeds its geysers could be just tens of meters below the surface. Enceladus may also be an easier place to operate a spacecraft—the region around Europa is crackling with intense radiation.

Some scientists are therefore advocating a return to Saturn’s moons (Enceladus and the fascinating cloud-covered Titan) as NASA’s next big outer solar system adventure, instead of Europa.

Whether or not EAGLE flies, look for Wray and his NASA Academy classmates to figure in future plans to visit Enceladus. In the meantime, he’s off to graduate school at Cornell, where he’ll work with planetary scientist Steve Squyres on new high-resolution pictures soon to be coming back from Mars. Not bad for a kid just out of college.