The MOL-Men Come Into the Light

A reunion—and newly declassified pictures—provide more detail on the military’s secretive space station project of the 1960s.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d7/ca/d7ca2c8d-1394-4a9c-91dc-e4c8ad8f8709/mol_concept.jpg)

In the late 1950s, with the Cold War in full swing, U.S. spy agencies thought they had a solution to reconnaissance behind the Iron Curtain. The U-2 could fly at altitudes in excess of 70,000 feet, where it was thought to be unreachable by Soviet aircraft or missiles. This was proven wrong on May 1, 1960, when Francis Gary Powers was shot down over the Soviet Union.

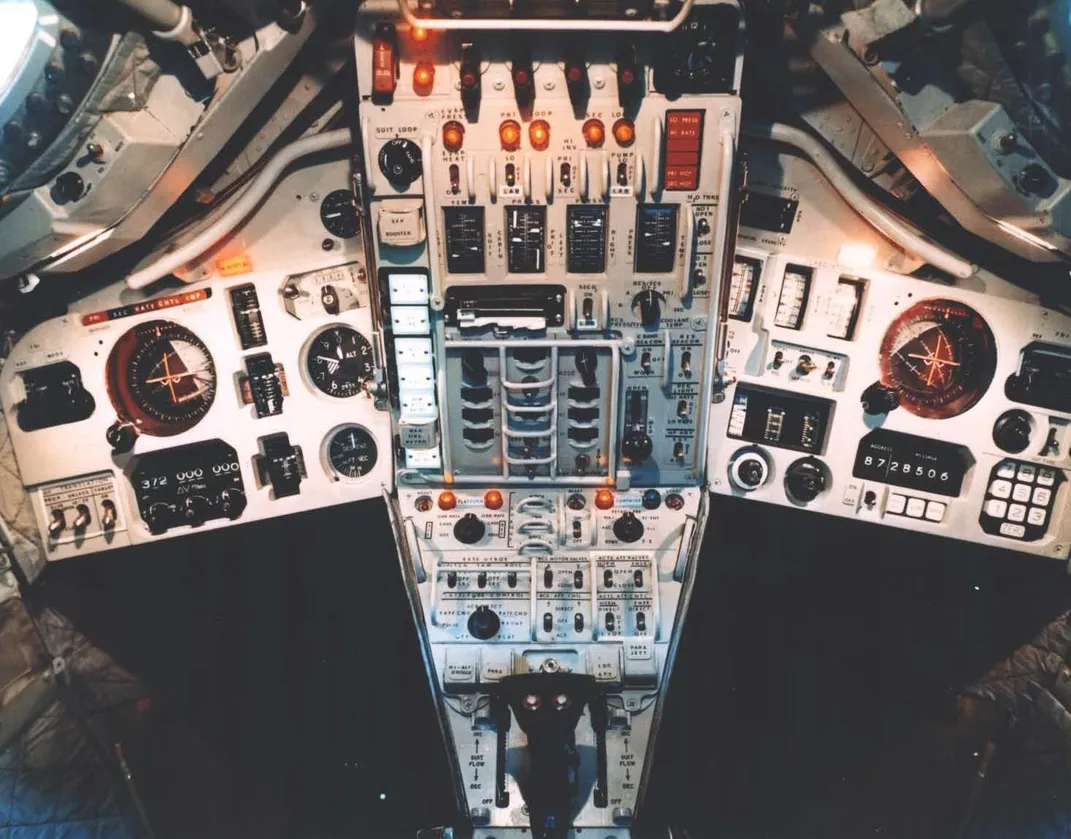

So the U.S. Air Force started making plans for an even higher spy platform—in space. This idea, announced officially on December 10, 1963 as a “single use laboratory” to “prove utility of man in space for military missions,” was called the Manned Orbiting Laboratory, or MOL. Astronauts would ride to their spartan space station in the orbital transportation of the day—a Gemini B capsule based on the one NASA was using to prepare for Apollo moon missions.

MOL was a top-secret program, and was described to the public as a laboratory. In actuality, it was going to be a spy platform with state-of-the-art cameras and other surveillance equipment provided by the National Reconnaissance Organization. But MOL was cancelled before the station was launched, and the small corps of military astronaut-spies was disbanded in 1969.

Much of the information about the project, which was known within the NRO by the code name “Dorian,” has only recently been declassified. Last October the agency hosted a symposium at the Air Force Museum in Dayton, Ohio, where it handed out a book, “The Dorian Files Revealed: A Compendium of the NRO’s Manned Orbiting Laboratory Documents.” The symposium also included a panel discussion with five of the eight surviving MOL astronauts: Bob Crippen, Dick Truly, Al Crews, Karol Bobko and James Abrahamson. Seventeen MOL-men were selected in all, six of whom went on to fly on NASA’s space shuttle after the MOL program ended. Also on the panel was the technical director for MOL, Michael Yarymovych.

Each panelist shared anecdotes from his time with the program. Abrahamson identified the main reason for MOL’s cancellation: Unmanned satellites could do the same thing more safely, and for less cost. Spying on the ground from orbit, he said, would have been like looking through a straw, and would have required a human touch to get the most accurate images.

Crippen believed that the skills he learned working on space hardware for the Air Force put him in a good position when he was picked up by NASA, and he became the first of the MOL refugees to reach orbit on the first space shuttle mission in 1981. He recalled being surprised to find out that the toilet system on NASA’s Skylab space station of the 1970s was pretty much the same one developed for MOL.

All of the panelists said they were surprised to learn of MOL’s cancellation in 1969. One heard the news while driving to work. Yarymovych was in the middle of testifying to Congress when someone handed him a note. And so ended the nation’s first—and so far only—attempt to launch a military space station.

Al Hallonquist is an aerospace historian.