Moments and Milestones: Can You Hear Me Now?

When radio communication took to the air.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/FM-2011-moments-and-milestones-FLASH.jpg)

Everything in the military works on the basis of command and response, but if the troops can’t hear the command, how are they supposed to respond? That was the dilemma that confronted the U.S. Army’s earliest proponents of aircraft. From the beginning, the pioneers recognized that in order to control the fleets of aircraft they envisioned, radio communication aboard airplanes had to be developed.

Although the early days are recorded only sketchily, in a March 1919 account in the Official U.S. Bulletin, a daily U.S. government publication, two names show up: H.M. Horton, a captain, and C.C. Culver, a colonel, both of the Army’s newly minted Air Service. At a 1910 air meet in the Sheepshead Bay section of Brooklyn, New York, the two went up in an airplane and sent a radio signal from a transmitter credited to Horton, and the signal was received on the ground by a receiver built by Culver.

According to the same account, Culver was dispatched to San Diego, California, in 1915, where he apparently led efforts to advance radio technology even further. In September 1916, a message was transmitted between two airplanes in flight, and in February of the following year, voice communication between an aircraft and the ground was finally established.

One of the challenges airborne radio confronted was the need for a ground. Radio theory says that energy transmitted by an antenna completes the circuit by returning to the radio through the earth to a conductor referred to as the “ground” wire. Among the best known of the early airborne radio pioneers is an Army lieutenant named Paul W. Beck. By 1911, when Beck conducted an aerial demonstration of a keyed radio transmission with a Western Wireless Equipment Company set, airplanes were being made of metal parts, and the mass of the parts had become the ground. Problem solved.

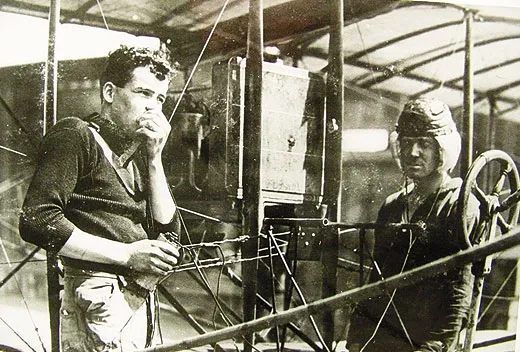

The antenna was a 95-foot length of wire made of fine phosphor-bronze strands and weighing just an ounce and a half. At a demonstration in January 1911 near San Francisco, Beck carried aloft a 29-pound cabinet that sat in his lap while he tapped out code with a key on its top. It was likely not the first demonstration of airborne radio, but many accounts credit Beck for the first, possibly because there’s a picture of him sitting in a Wright Model B, a dapper, uniformed figure with the big box in his lap and large words on it reading: “Type A-4 Aeroplane Wireless Telegraph Set. Developed By Western Wireless Equipment Co.” None of the other pioneers had their picture taken while holding a radio with a big label on it.

The accompanying account in the April 1911 Journal of Electricity, Power and Gas, authored by one Earl Ennis, makes the claim of first airborne radio transmission, though he is careful to limit the claim to just that: the transmission. He says that engine noise made it impossible for a radio aboard the airplane to receive the reply.

Still others credit Canadian James McCurdy with a successful radio transmission and reception as early as August 1910, and, curiously, Ennis himself may have done it as early as June of that year, according to Electronics in the West by Jane Morgan (National Press Books, 1967).

Beck was shot to death by a jealous husband in 1922. None of the pioneers’ names are well known today, but then none of them invented the radio; they were simply adapting it to one of its most elegant and enduring applications. Pilots and air traffic controllers have been using the radio to maintain safe airways for decades. While it was voice transmission that dominated airborne radio, 100 years on, aviation will begin to move away from voices on the radio to the transfer of messages via digital codes—still radio but without the human voice. The messages will appear on screens, where pilots can read them...aloud, if they miss the sound.