Moments and Milestones: Mile-High Man

Moments and Milestones: Mile-High Man

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Brookins4_FLASH.jpg)

When the Wright brothers were first experimenting with powered flight, Walter Brookins was just a teenage kid hanging around their Dayton, Ohio home. He must have ingratiated himself with the family, whom he had known since he was four, because the Wrights, who called him Brooky, promised to build him an airplane one day. He ended up working for the brothers, and even setting a flying record as their employee, but after a quarrelsome split, he left the Wright organization, obscuring his accomplishments.

Brookins was born in Dayton in July 1889. At one time he was a student of Katharine Wright, Orville and Wilbur’s sister and an Oberlin College-educated schoolteacher. Orville in particular took a liking to young Brookins and selected him to be the first person he would train to fly. By 1909, six years after the Wrights’ first flights, the airplane was attracting crowds at air meets and exhibitions. Katharine and the brothers had deep misgivings about the daredevil nature of exhibition flying, but Orville and Wilbur finally formed a team of fliers in 1910 (see “Ladies and Gentlemen, the Aeroplane!” Apr./May 2008).

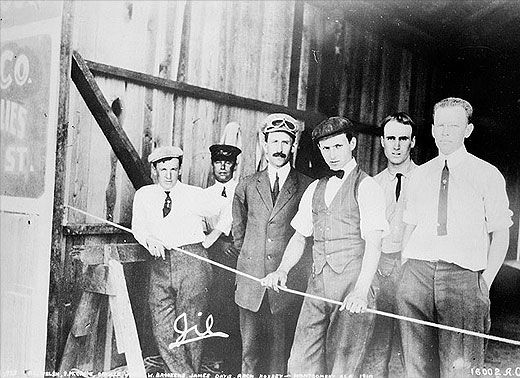

According to accounts of the period around 1910, Brookins was the team’s most daring and accomplished member. He reportedly flew solo after only two and a half hours of Orville’s tutelage, and then trained two other members of the team in Orville’s absence.

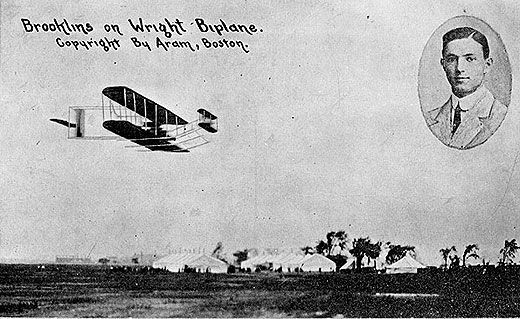

Photographs of Brookins reveal a clean-shaven, youthful fellow who could be played by Ben Affleck in a high-collar shirt, cravat, and a newsboy cap. One newspaper account describes him as “slight,” which would have been to his advantage in one of his more demanding stunts, during which he’d rack the wispy airplane over onto one wingtip in a 90-degree bank and fly a tight circle that would have pulled more than two Gs.

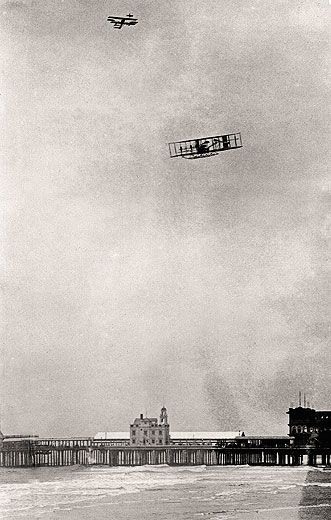

It was in Atlantic City, New Jersey, on July 9, 1910—exactly 100 years ago—that Brookins became the first flier to take an airplane more than a mile up. A mile! (Actually, Brookins went nearly 900 feet higher, but “one mile” made for sensational headlines.) The feat won the Wrights $5,000, but for Brookins himself, the contract salary was $20 a week plus $50 per day of flying; all prize money went to the team.

Possibly disgruntled at the contract pay and at not getting a share of the prize money, Brookins began negotiating for a job with the Pioneer Aeroplane and Exhibition Company of St. Louis. The Wright brothers, who took to litigation as if they had been born in a courtroom, immediately threatened to seek an injunction to ground him. The threat marked the end of the professional relationship between the Wrights and Brookins, who had read enough newspaper stories about himself to decide to go it alone. During his solo career, Brookins set one long-distance record after another. An item in the February 6, 1911 Washington Post summarizes succinctly the effect of these accomplishments: His wife, Grace, suing him for divorce, charged him with desertion.

Brookins worked for a time in Milwaukee as a chauffeur for a retired industrialist, and later became a partner in a Hollywood, California company called the Davis-Brookins Aircraft Corporation, which had been formed as the patent holder for the Davis airfoil. That airfoil was famously used on the Consolidated B-24 Liberator bomber of World War II. Brookins died at home in Hollywood in 1953 after a four-month illness and was buried in the Portal of the Folded Wings, a shrine for pilots.

Celebrating the centennial of the first flight to exceed one mile in altitude is an idea that is unlikely to catch on in an era when light airplanes routinely fly at more than 5,000 feet and tourists are reserving seats for rides to the edge of space. But if you’re on a quiz show and they ask who was the first man to fly a mile high, remember ol’ Walter.