Moments and Milestones: Now, That’s Good Mileage

Moments and Milestones: Now, That’s Good Mileage

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Moments_and_Milesstones_good_mileage_FLASH.jpg)

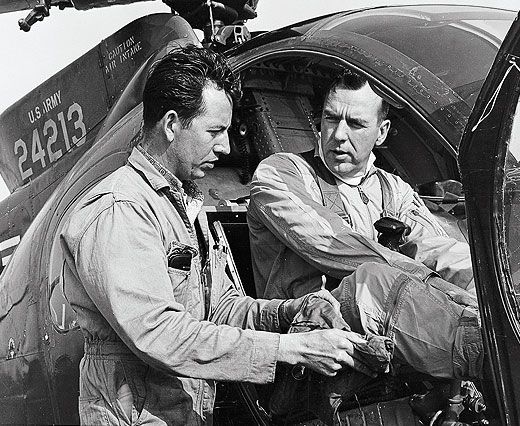

In April 1966, the U.S. Army OH-6A, which would later win accolades for its performance as a scout helicopter in Vietnam, set 23 world records for distance, speed, and altitude; more than four decades later, many are unsurpassed. Perhaps the most incredible of these unbroken records is the longest nonstop, unrefueled flight by any helicopter. Bob Ferry, a retired Air Force lieutenant colonel and Hughes test pilot, took off from the helipad at the Hughes Tool Company in Culver City, California, and landed at Ormond Beach, Florida, 15 hours and eight minutes—and 2,213.1 miles—later. Ferry had been expected to land in Miami, where the national media were waiting. Due to weather conditions, he ended up on a deserted beach hundreds of miles north.

The OH-6A staggered into the air carrying three times its empty weight. More than a ton of the aircraft’s weight was fuel, the rear seat and copilot’s seat having been replaced with auxiliary fuel tanks, requiring Ferry to sit inches from volatile jet fuel. “Bob went on a special diet for weeks before the flight, losing about 20 pounds so he could carry more fuel,” recalls Dick Lofland, the flight’s crew chief.

Helped along by a stiff tailwind, Ferry averaged nearly 150 mph, at times pushing the Volkswagen-size helicopter to altitudes of more than 24,000 feet, where it shared the sky with airliners.

A CV-7 Buffalo serving as the chase plane carried an official representative of the National Aeronautic Association, which documents all record attempts, and two of Ferry’s crew members. The relatively low speed, good range, and short takeoff and landing distances of the CV-7 made it a good choice to accompany a slow flying helicopter.

“I’m going to run you guys out of gas,” Ferry kidded the crew before takeoff. And sure enough, the CV-7 was forced to land in Tallahassee to refuel.

After the support crew arrived in Ormond Beach, they measured what fuel remained in the OH-6A. “There wasn’t enough left to fill a coffee can,” says Phil Cammack, the Hughes engineer who planned the flight.

The flight was sponsored by the Hughes Tool Company Aircraft Division, which hoped to beat a record set in 1965 by a twin-engine Sikorsky SH-3A, an aircraft 10 times heavier than the OH-6A.

“To fly coast to coast without refueling was iffy,” Ferry told me in 1990. “It was a challenge I couldn’t resist.”

From the seventh hour of the flight until just before landing, Ferry flew above 10,000 feet and wore an oxygen mask. “As he burned fuel off and the weight went down, he’d climb in altitude,” says Cammack. “The last two or three hours he was up about 24,000 feet.”

With no autopilot, Ferry had to stay alert and keep his hands on the cyclic and collective control sticks for the entire flight.

“When I was just three miles past St. Augustine, I got a low fuel warning light,” Ferry wrote in his official report. “I pressed on and it became a question of guts versus discretion as to how I would go.”

To those present at the landing, Ferry appeared strange, wearing knitted slippers for comfort instead of flying boots and an old leather flying cap rather than a helmet. When he told the locals that he’d come from California, they asked, “Where did you land last?” They didn’t believe he had flown non-stop and unrefueled from the West Coast.

Ferry’s career included 90 missions flown during the Korean War and six years of test flying at Edwards Air Force Base in California. In 1975, he made the first flight of the Apache attack helicopter at Hughes. He logged more than 10,000 hours in 125 aircraft. “He would break the sound barrier one day and fly a helicopter the next,” his wife Marti says.

Ferry died in February 2009 at age 85. “All Bob ever wanted to do was fly,” Marti recalls, “and he liked living on the edge.”