The Most Talented Aviation Pioneer You’ve Never Heard of

Starling Burgess beat the Wright brothers at their own game.

:focal(770x296:771x297)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f2/ab/f2ab1a05-bddf-41a2-8464-08c2478b5918/01-profile-starling-burgess-1911.jpg)

Starling Burgess designed a three-wheeled car with Buckminster Fuller. He married five times. He drove to Princeton to get Einstein’s help on a math problem. He designed three winning America’s Cup defenders, just as his father had. He built the first airplane to carry Tom Sopwith’s name. One of his aircraft landed on the White House lawn. Another was wrecked in Plymouth Harbor by Hap Arnold. He built swept-wing, tailless seaplanes so stable they could take off without the pilot touching the controls—in 1914.

Burgess was endowed with a bold, creative nature and mathematical and engineering skills to match. For nearly a decade, starting in 1909, he devoted his skills to aviation. However, “he was a terrible businessman,” says Llewellyn Howland III, author of No Ordinary Being: W. Starling Burgess (to be released this year by David R. Gordine Publishers). “He wasn’t dishonest, and he wasn’t stupid about money, but he always assumed the best about everyone. That was his fatal flaw.”

Dickensian Beginnings

Burgess was born into wealth and high Boston society on Christmas Day, 1878, the first child of Edward and Caroline Burgess. Edward’s passion and avocation was yachting. Starling excelled in a blend of his parents’ formidable aptitudes, which they encouraged: mathematics, mechanics, poetry, and, of course, sailing.

In 1883, his idyllic life was upended when the family’s sugar import business collapsed. Edward opened a small naval architecture practice and soon scored a commission to design an America’s Cup defender. His Puritan won handily in 1885. Over the next two years, Edward created two more boats that repeated the feat.

Commissions poured in. The idyll was briefly restored. But Caroline began suffering from “hysterical” maladies, treated with increasing doses of morphine and arsenic, and Edward died of typhoid fever in 1891, at age 43. That November, Caroline collapsed in the snow in front of Boston’s Trinity Church. She died only nine days before Starling’s 13th birthday.

Starling attended the Milton Academy and Harvard, where his mathematical and engineering genius blossomed; enlisted in the Spanish-American War and designed a machine gun; opened his own naval architecture firm; married and then suffered his wife’s suicide; published the first of several volumes of poetry; and courted and then married one of his best friends’ wives, the painter Rosamond Tudor. He was 26.

The new couple set up in the Massachusetts coastal village of Marblehead. Burgess opened a shipyard and assembled a crack team of shipwrights. Every ship they produced, from steam launches to trainers to yachts, was elegant in design and superbly crafted. His powered speedboats were the fastest in the world, and through them Burgess learned much about the gasoline engine.

“Like a Little Dancing Girl”

In September 1908, Burgess was invited by his friend and Harvard physics professor Wallace Clement Sabine to Washington, D.C., to see Orville Wright fly. Everything about the 1908 Wright Military Flyer was a revelation. “The flying machine herself seemed of fairy-like proportions; quite too unsubstantial to accomplish what was expected of her,” he later wrote in his unpublished autobiography. As the airplane was launched and sailed over Burgess’ head, “[t]ears came unbidden to my eyes. Shall I ever forget that moment!” The next day, Orville Wright crashed, and his passenger, Army Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge, was killed—the first to die in a powered airplane.

Despite the tragedy, Burgess turned from his promising maritime career to pursue powered flight. His first foray was a partnership with a man about whom Samuel Langley, Octave Chanute, the Wright brothers, and even Glenn Curtiss could agree: They had all worked with—and despised—Augustus Herring.

Herring was an ex-assistant to Langley and had piloted Chanute gliders. He visited the Wrights’ camp in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, and later tried to force the brothers into a partnership, claiming equal success in powered flight. He partnered with Curtiss, based on a pretense of owning patents that would circumvent the Wrights’. (The Wright patent for the three-axis control of flying machines was a hurdle for early airplane manufacturers. The Wrights held that it covered the principle of control, while others, especially Curtiss, claimed it covered only their particular control mechanism—wing-warping. Early manufacturers had a choice: Try to avoid the Wrights’ patents with novel designs, openly risking lawsuits and injunctions claiming infringements, or pay for a license from the Wrights. By 1909, when Burgess first contacted Herring, no U.S. manufacturer had requested a license.)

In late 1909, Burgess visited Herring’s New York City workshop. Regardless of Herring’s past—of which Burgess may have known nothing—the would-be aviation pioneer had what Burgess needed: some design and construction experience, a head start with a partially completed airplane, even an engine and some propellers. And Burgess had excellent facilities. They shipped Herring’s incomplete airplane to Marblehead and signed a contract creating the Herring-Burgess partnership.

Their first airplane, called the Flying Fish, was rushed to Boston to participate in the February 1910 Aero Show. Its fine workmanship drew attention. One man told Burgess, “Your ship is like a little dancing girl on her toes. The others are like cows.” Another visitor, Greely S. Curtis, had flown with Otto Lilienthal, and, thanks to his successful “fire stream gauge,” which measured the flow from firefighting hoses, was financially secure. Curtis liked what he saw.

The Flying Fish was moved to frozen Chebacco Lake, northeast of Boston. On February 28, 1910, Burgess got Augustus Herring to actually fly an airplane. It had to perform. A Kansas showman named C.W. Parker had already offered them $5,000 for the machine. Herring opened the throttle, and 120 yards later came down hard, smashing the skid landing gear.

Herring’s clumsy piloting was partly the result of the bizarre controls he and Burgess had designed. The forward elevator was controlled by one foot pedal, the throttle with another. The rudder was controlled by thumb devices: one for left, the other for right. To avoid the Wrights’ patent, the airplane had no ailerons; instead, a row of six triangular fins was mounted on the top wing (hence the name Fish). Parker, whose criteria for safety were evidently as dubious as the Flying Fish’s airworthiness, handed over a check. The ship was repaired and shipped to Kansas. Burgess was in the airplane business.

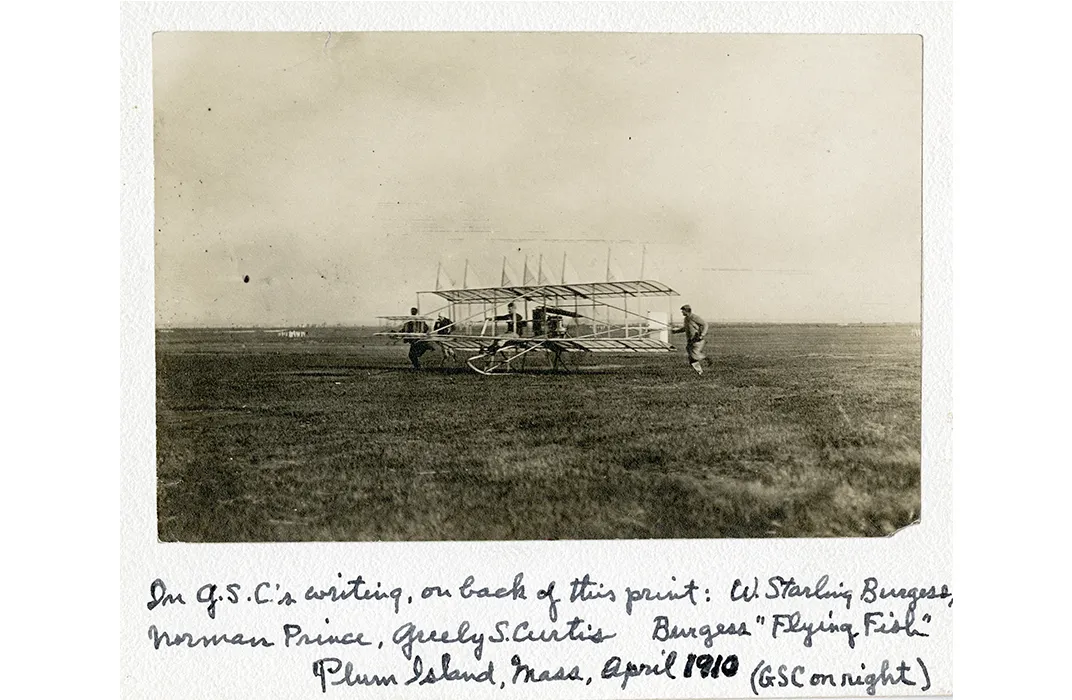

In April 1910, the second Flying Fish (now with eight stabilizing fins) was shipped on the Burgess steamer Ox to nearby Plum Island. (Burgess’ wife, Rosamund, was the certified steam engineer on board.) Herring and Burgess both flew, as did brave but inexperienced William Hilliard. By the end of June, he could complete a full turn. Norman Prince, Burgess’ friend and the future leading founder of the Lafayette Escadrille, got a chance at the controls, as did Greely Curtis, the wealthy admirer from the Boston show. Although Curtis demolished the Flying Fish II, Burgess invited him to join the company, which produced a third version of the Flying Fish with improved controls and without the useless fins. Five were built; four were sold.

Herring’s role diminished. He was no longer the only pilot, and his controls and propellers were discarded for better versions. Burgess had design talent and Curtis had the money. “It didn’t take Starling long to figure out—and I say this kindly—that [Curtis] was a potential meal ticket,” says Bill Deane, president of the Massachusetts Aviation Historical Society. Howland adds: “Burgess always needed a patron, and Curtis’s skin was in the game all the way.” Their venture, called The Burgess Company and Curtis, was established, and Herring left Marblehead for good.

As Models B, C, and D evolved, Burgess and Curtis remained on an experimental course, still grappling with the problem of a non-infringing control system. Burgess and Hilliard competed at the Harvard-Boston Aero Meet in September 1910, where the results were less than impressive. But Englishman Claude Grahame-White, who dominated the meet, was so impressed with the Burgess airplane’s construction that he commissioned Burgess to manufacture several Model E’s, a Farman adaptation built to Grahame-White’s specifications.

Aviation Royalty

Burgess’ handiwork also attracted Wilbur Wright. Although Burgess, like everyone else, had tried to avoid the Wright patents, once he met Wilbur, Burgess flaunted conventional wisdom.When the two met at the New York Yacht Club, Wilbur made him an offer. For a $1,000 royalty per airplane, Burgess and Curtis would be the sole U.S. Wright licensee, paying a fee for each airplane built, but free from infringement lawsuits and with other protections the Wrights could offer. They could purchase as many Wright engines, propellers, and other components as they wished. Burgess and Curtis decided the deal was a safer bet than chancing a legal fight over the control patent. And Burgess wanted to be associated with the Wrights because he thought Wilbur was a genius. “Wright’s eyes glowed with animation as he spoke, and through them, rather than any outstanding mark of the man’s appearance, shone his greatness,” he wrote in his autobiography.

Taking Wilbur’s advice, he enrolled in the Wrights’ winter flying school in Augusta, Georgia, to learn fromFrank Coffyn. With classmate Norman Prince, Burgess delighted in the ease of flying the Wright machine. He and his wife visited Dayton in March 1911, and Burgess returned to Marblehead, armed with real flying skills, the confidence of a man he deeply admired, and the exclusive U.S. license.

The new Burgess-Wright Model F, nicknamed the Moth, was nearly identical to the Wright B. The Burgess catalog ultimately listed 30 changes to the Wright design, promising better safety, performance, durability, even appearance. It gleamed: nickel-plated fittings, ash and spruce with spar varnish over the aluminum paint, bright white sailcloth made especially by Messrs. Wilson and Silsby, Boston sailmakers.

On April 13, 1911, Burgess made the first flight of a Model F at his new flying school in Mineola, New York. Attached to the aircraft was an homage to his father—a miniature signal pennant copied from the Puritan. Burgess was elated with his machine. Then the Moth was gone.

Charles K. Hamilton, a hell-for-leather type who had flown dirigibles and served as a pilot for the Glenn Curtiss team, appeared at the field and offered to buy the machine. Burgess quoted him $5,000. As Burgess remembered it, Hamilton took off a boot, retrieving and calmly flattening five $1,000 interest-bearing notes into Burgess’ hand. Hamilton towed the airplane to his home in Connecticut. It was back in Marblehead soon enough. Completely untrained on Wright controls, Hamilton demolished it on his first attempt to fly, and returned it for repairs.

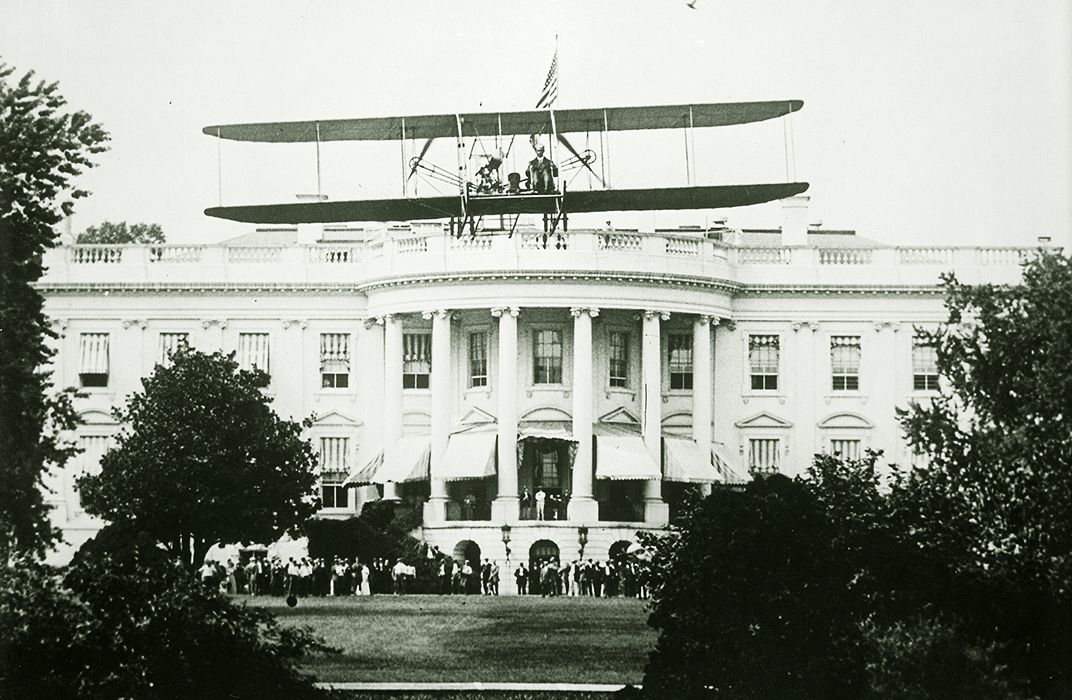

Eventually, the school moved back to the Boston area and soon Burgess-Wright Model F pilots were making headlines—none more so than Harry Atwood. Ostensibly a Burgess instructor, he quickly became enamored with long-distance flights all over New England. He offered to fly Mayor John “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald of Boston (Fitzgerald declined) and buzzed the Harvard-Yale crew races in New Haven. After a flight to New York City, where he circled the skyscrapers and dazzled the throngs below, Atwood was offered $1,000 to continue to Washington, D.C.

He started out from New York on July 4. After a series of mishaps in New Jersey (a crash landing in the surf, swapping the wreck for Hamilton’s Burgess-Wright, and killing a dog that ran into a spinning propeller), Atwood made it to Washington. He landed on the White House lawn and rolled to a stop, without brakes, just 30 feet shy of the not-too-nimble President Taft. A month later, Atwood made the first flight from St. Louis to New York. (The White House Model F, now in the collection of Ken Hyde’s Wright Experience in northern Virginia, is the only restorable Burgess-Wright aircraft in existence. The remnants of a Herring-Burgess Model A are in storage at the National Air and Space Museum.)

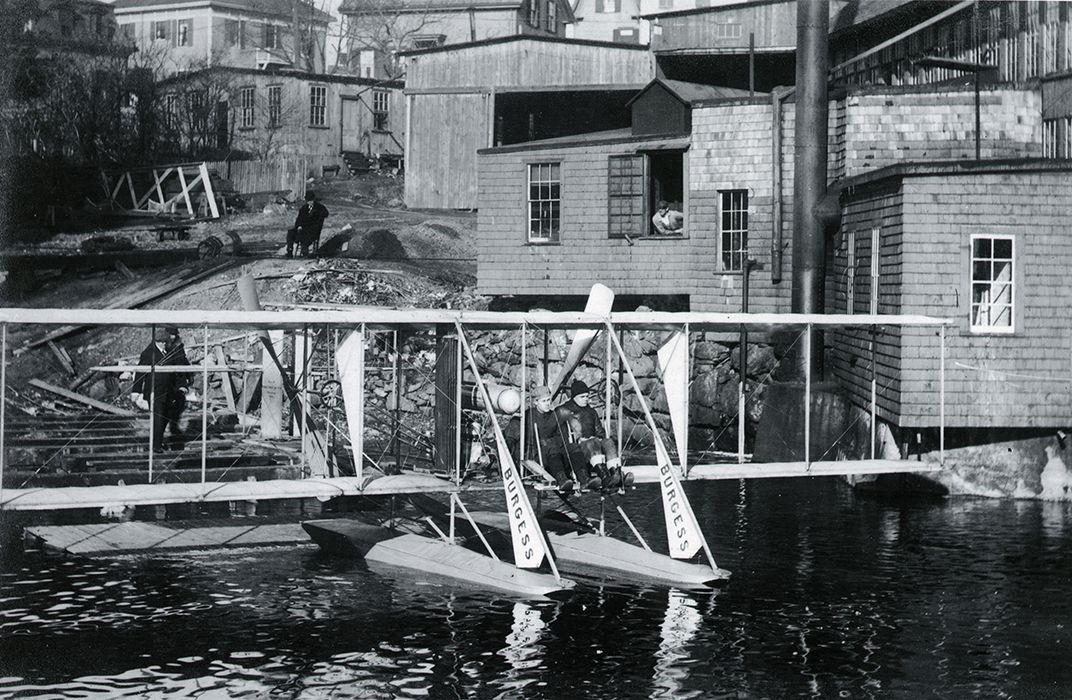

As his airplanes’ reputation spread, Burgess began to break from the Wright mold. Despite Wilbur’s skepticism, Burgess designed for the Model F a set of catamaran-style floats whose lower surfaces were arranged like upside-down stairs, or “stepped.” On October 25, 1911, Clifford Webster took off from Marblehead Harbor, and the Burgess worlds of water and air merged.

The hydroaeroplanes, or hydros, as they were called, attracted a lot of press. Their sales roughly equaled those for the land-based Model F. Glenn Curtiss was already aggressively developing hydros, and according to Howland pondered what to do about Burgess as a potential competitor. “[Curtiss said] ‘Maybe we should shut him down. Maybe we should get him off our patents,’ ” says Howland. “But then Curtiss said, ‘Well, the hell with it, we got a lot more important things to do than worry about that.’ ”

One of Harry Atwood’s students, a reporter named Phillips Ward Page, used the Burgess-Wright Hydro to make movies for New York’s Aviation Film Company. Lieutenant Hap Arnold flew them in an action film (The Military Air Scout) and a romance (The Elopement). Arnold made the first military distance flight—42 miles, from College Park, Maryland, to Frederick— in the U.S. Signal Corps Aeronautical Division’s Burgess-Wright Model F, and trained aspiring pilots in that model. He had also seen another example of Burgess craftsmanship up close. On a freezing day in Marblehead in 1912, Burgess had demonstrated a lightweight life preserver he’d developed by putting it on and leaping into frigid water, explaining its features to observers as he bobbed around.

A Burgess-Wright Model F, modified with a Gnome rotary engine and non-Wright controls, became the mainstay of Thomas Sopwith’s first flying school in Brooklands, England. Sopwith rebuilt it with British parts to compete in the British Empire Michelin Cup. It was the first airplane to bear the Sopwith name.

By the late fall and winter of 1911, the Burgess and Wright Companies were fighting over payments, shipments, and royalties. “It was basically a mess within eight months from the time they signed the agreement,” says Howland. “But for all the huffing and puffing, they really didn’t fall apart for three years. The Wrights still wanted to use Burgess, and Burgess thought he was still somewhat protected by the Wrights. It’s a fascinating dance.”

In the meantime, Burgess snapped up several recently released Wright employees: Howard Gill, a wealthy pilot; former exhibition star Walter Brookins; and Wright Company manager Frank Russell. With confidence, Burgess moved deeper into aircraft design.

The first venture was an attempt to win the $15,000 Scientific American prize to create the United States’ first twin-engine aircraft. Working with Howard Gill, Burgess employed two engines—a 60-horsepower V-8 Hall Scott and a 30-hp Wright four-cylinder—mounted in tandem at the nose. Each drove a pair of propellers: one tractor, the other pusher. The airplane met every requirement for the prize, and was the only one to be entered by the July 1912 deadline. But since there were no other contestants, the sponsor decided there was no competition and withdrew the prize. Burgess and Gill received nothing.

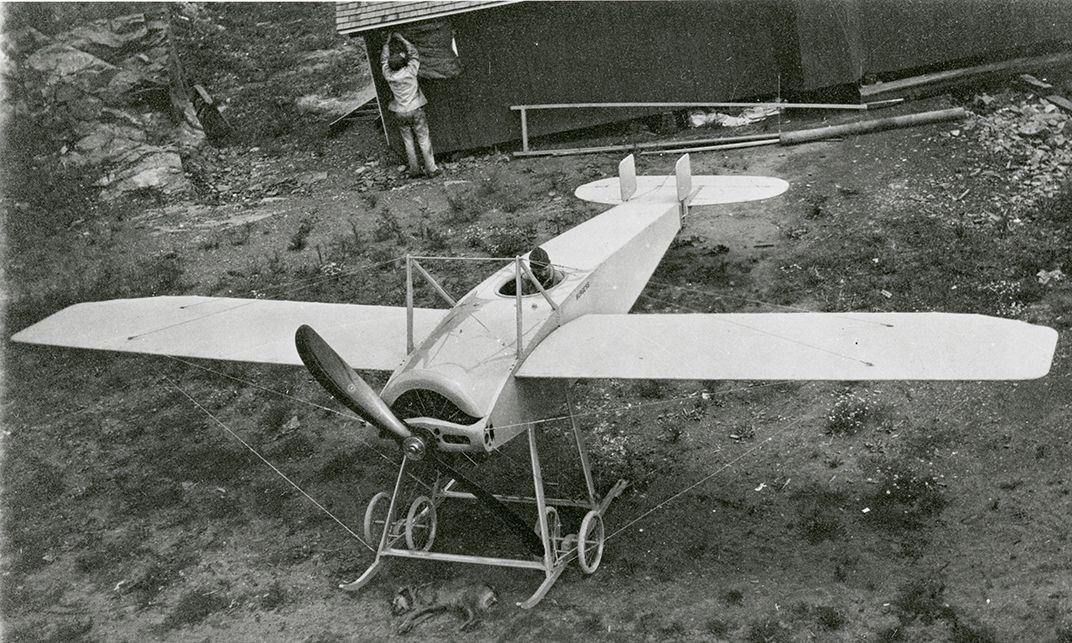

The second project focused on the fourth annual Gordon Bennett Cup race, which was coming to Chicago in September 1912. Burgess’ friend Norman Prince and Prince’s business partner, Charles Dickinson, formed the Cup Defender’s Syndicate to win the race. With only six weeks to spare, they commissioned Burgess to deliver a brand-new airplane built around a monster 160-hp Gnome engine. Burgess soon rushed a sturdy little monoplane to Chicago.

Burgess, the syndicate, and the race committee were soon embroiled in an epic argument over the choice of pilot and type of controls. Newly minted aircraft builder Glenn L. Martin was finally chosen to fly. He insisted on using his own controls and smaller wings, which arrived in Chicago just in time for Dickinson to declare the entire episode a fiasco and end the effort. French aviator Jules Verdrines easily streaked to victory in his Deperdussin.

For Burgess, the fiasco was compounded by a far greater loss: Five days after the race, Howard Gill was killed in a mid-air collision.

The Dunne Effort

Over the next year, Burgess found moderate success with military designs, three new hydros, and a flying school. He and Curtis let the agreement with the Wrights wind down and formed a new company.

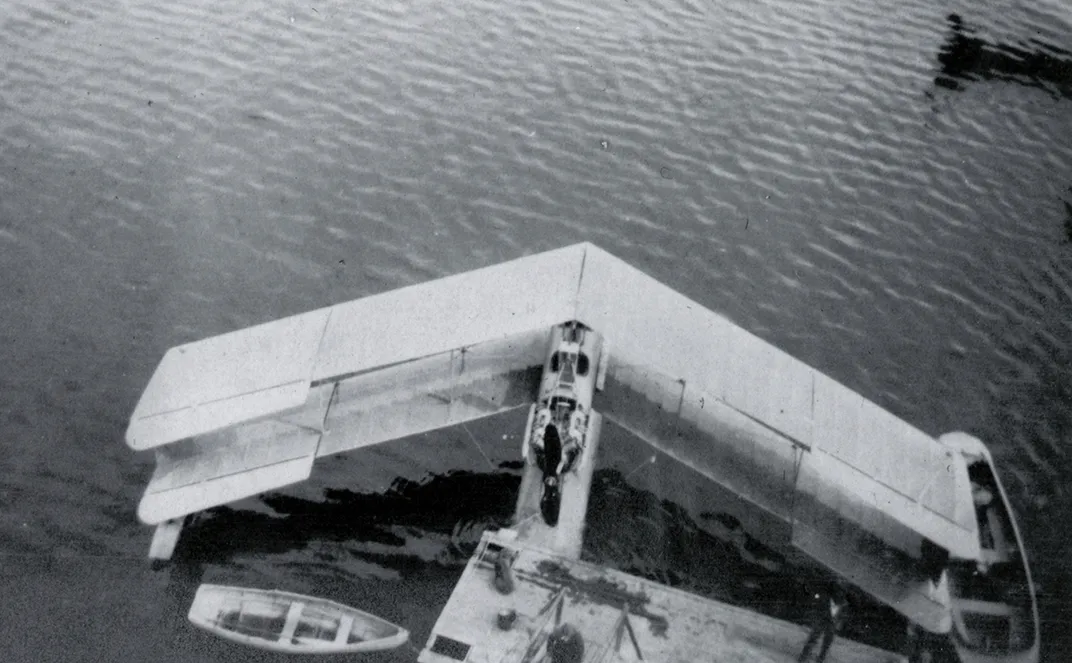

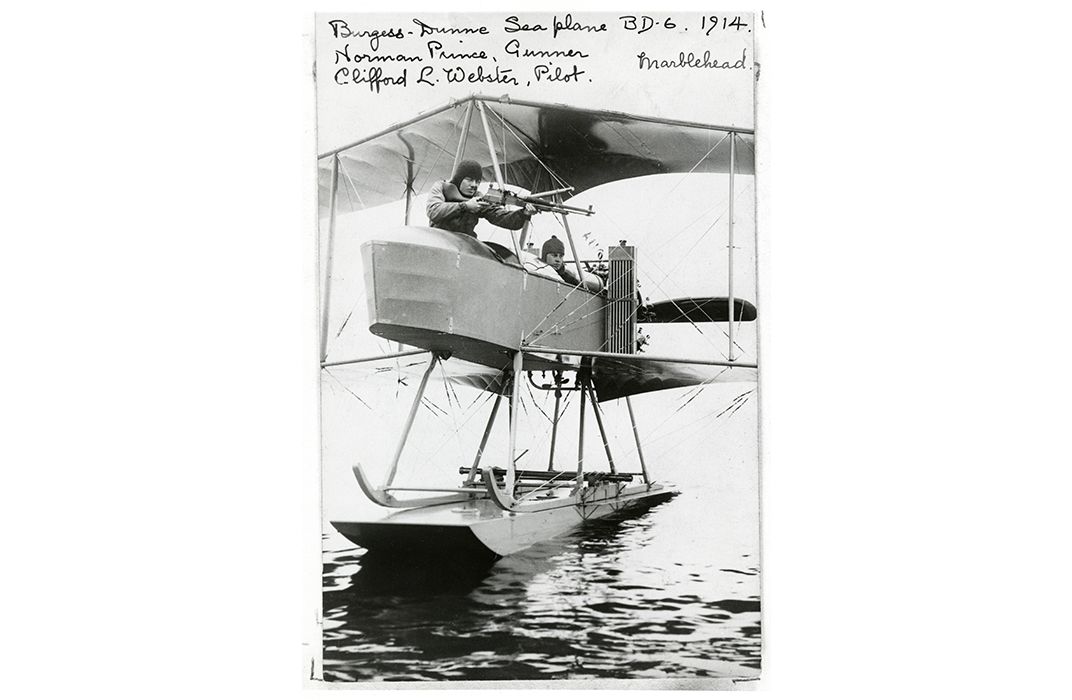

Burgess traveled to England in the fall of 1913 to see for himself the remarkable work of British designer J.W. Dunne. Dunne had achieved automatic stability with a radical design he first developed in 1906, a swept-wing, tailless biplane whose wing camber gradually twisted down from the root to the tip. Burgess proposed that he be the sole licensee of the Dunne patents, and also develop a hydroaeroplane version. Dunne accepted the deal but, like Wilbur Wright, was skeptical about the hydro adaptation.

In January 1914 Burgess cracked up the first Burgess-Dunne hydro. On the next flight, Clifford Webster easily rose off the water, then climbed, dove, made steep turns, and tried repeatedly to stall. The airplane righted itself every time. When Webster took his hands off the controls, levers locked in place with ingenious ratchets. The Burgess-Dunne flew itself.

On May 2, a committee from the Aero Club of America bobbed in a boat in the harbor, the members hardly believing their eyes. Even with a 40-mph wind, Webster took off hands-free, and remained so as he flew straight at the boat and in circles. Toward the end of the flight, he cut off the engine and lifted his hands in the air again. The Burgess-Dunne spiraled toward the surface. Webster took control with 100 feet to spare and shot back up. He came straight at the committee again, descending, no-hands, until about 50 feet off the water, when he gently dipped the airplane down and landed within a few feet of the boat. The Aero Club’s report was breathless.

For the next two years, Burgess-Dunnes were built for the U.S. military, Canadian Aviation Corps, and wealthy private patrons. Almost all were two-seaters—some tandem, some side-by-side. The Signal Corps version was outfitted with a machine gun. Flying them was so easy that Webster soloed two novices, each with less than two hours’ total instruction. The airplane won Burgess the 1915 Collier Trophy, U.S. aviation’s highest honor.

But in wartime, slow, safe, and stable were not priorities. Neither were unique, two-levered controls. The Burgess-Dunne could not be a bomber or a nimble fighter, and there weren’t enough wealthy sportsmen to support a civilian market. “Ultimately, Starling wasn’t a manufacturer,” says Howland. “He was fascinated by flight itself. He loved creating aircraft, but not multiple copies. There was a degree of realism that [Glenn] Curtiss had and Sopwith had, that Burgess just didn’t have.” A month after winning the Collier Trophy, the Burgess Company was sold to Glenn Curtiss and became the Burgess division, building Curtiss aircraft.

Burgess continued on with the division until he enlisted in the Navy in 1917. There were orders for more conventional designs, mostly military trainers. The company pushed through World War I with the largest production run it ever had: 460 Curtiss N-9s, which Starling Burgess neither designed nor improved.

On the night of November 7, 1918, a fire completely destroyed the main plant. By then, the war was over, and the military contracts dried up. The Burgess division closed, and Starling ultimately returned to the sea and his beloved yachts. “It’s very easy to criticize him, but look at all he went through,” says Deane. “He was like a child in many ways.”

In June 1914, as Burgess was experiencing the first successes with the Burgess-Dunne, his oldest child, eight-year-old Edward, drowned. Eleven years later, his marriage to Rosamond Tudor began to falter. Burgess married three more times. He explored automobiles, submarines, and ever-advancing yachts. Burgess entered the America’s Cup race as designer and competed against his one-time novice customer Thomas Sopwith. Just as World War I had doomed Burgess’ aviation company, it had made Sopwith a wealthy legend. Sopwith financed and skippered two America’s Cup Challengers in the 1930s. Burgess’ design beat him both times.