The Museum That Fell From the Sky

An Ohio native preserves the story of the Navy’s first rigid airship.

:focal(2559x1672:2560x1673)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d4/8f/d48f4140-2f7f-4493-b5ca-29622222e3e4/shenandoah.jpg)

Famous museums, like the Guggenheim in New York City or the Louvre in Paris, often reside in imposing buildings. Theresa Rayner’s USS Shenandoah Museum lives in a refurbished camping trailer towed behind a pickup truck. But inside this humble trailer is a priceless collection of memorabilia recalling the U.S. Navy’s first rigid airship, all lovingly curated and cared for by this Ohio woman with a passion for history and preservation.

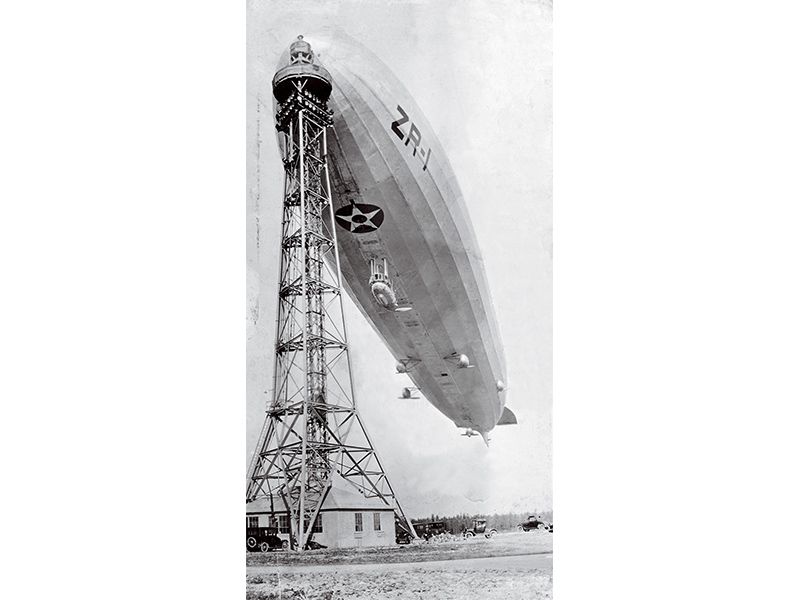

The 680-foot-long USS Shenandoah was the pride of the U.S. Navy when christened in 1923. Its mission was to provide airborne surveillance for the fleet; to prove its capability, in 1924 the Shenandoah embarked on test flights across the United States. Soon, mayors, governors, and congressmen were requesting that the Shenandoah fly over their regions. In 1925, the airship was ordered on a tour of Midwest state fairs; it was on this trip, on September 3, that the Shenandoah was destroyed in an early morning squall above southeast Ohio. Of the 43 men on board, 14 were killed, including the captain and four other officers.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e9/cb/e9cb9dc9-5cad-4f5c-aefc-ee8f85c568c5/15l_dj2021_trailerbooksigning_live.jpg)

Engine parts, food from the galley, and personal effects of the crew were strewn about in fields and forests; shortly after the crash, thousands of looters rushed to the site and scavenged anything that could be torn loose or taken. The Department of Justice and the Ohio National Guard arrived to secure the area in late afternoon, but by then the damage was done. Government officials took a dim view of this rampant theft. In the weeks following the disaster, four truckloads of Shenandoah items were confiscated by federal agents in door-to-door searches throughout the region. Despite these efforts, many of the items became treasured family heirlooms, displayed for decades in parlors and living rooms. These are the artifacts that found their way to Rayner’s homemade museum on wheels, where visitors can see them up close and hold a bit of history in their hands.

“We still get donations after all these years,” says Rayner, “like when someone is clearing out an older relative’s home, and they come across a piece of Shenandoah’s framework in the attic. Some families had these things hidden away for decades, fearing the government might come for it someday.”

Rayner’s late husband Bryan grew up near Neiswonger Farm, where the bulk of the wreckage fell. As a boy, Bryan collected anything he could find relating to the wreck of the Shenandoah. His family has a connection to the event: The Rayners, along with other local residents, sold soda pop and water to the thousands who traveled to view the site.

News clippings, photographs, and pieces of the ship continued to accumulate in Rayner’s Garage in Ava, Ohio, the family’s towing business. “Bryan had quite a collection when we got married,” says Rayner. And the couple showed the collection to anyone who asked to see it.

The idea of a more permanent museum came up after the Rayners were asked to set up a Shenandoah history display in a local store window. A portable museum was proposed, and someone traded the Rayners a used travel-trailer that fit the need. A neighbor built custom glass display cases, and other donated materials soon arrived. The USS Shenandoah Museum was ready for the road in 1995. The museum-on-wheels made the couple’s collection accessible to a whole new audience. “We started visiting schools, scout meetings, church socials, and we gave tours of the museum to people just passing through,” says Rayner. The increased exposure resulted in more donations and acquisitions. The Rayners bought a larger trailer when the collection outgrew the original.

Treasures displayed inside the museum include various pieces of the ship’s duralumin framework, sections of the silver outer cover, fragments of the airtight gas cells, plus assorted ropes and rigging. Items from the ship’s galley include cups and plates used by the crew, plus a sugar bowl with the sugar still inside. There’s an impressive scale-model of the ship, and original sheet music of the mournful song “The Wreck of the Shenandoah” by Maggie Andrews.

During the Depression, some people repurposed their Shenandoah relics into household items. “We have a lampshade made from Shenandoah canvas,” says Rayner. “When this particular woman needed to replace a tattered lampshade, she stitched up a new one made from fabric she recovered from the wreckage.” There’s also an aluminum wash basin from the ship that had been converted into a hanging planter, eventually discarded by the owner. “We found that one behind a house in some weeds,” recalls Rayner.

Occasionally, the Rayners would buy pieces at local auctions and rummage sales. Bryan was late for his own surprise 50th birthday party because he’d heard that a six-foot-long section of Shenandoah framework was to be sold at an estate auction that day in a nearby town. He won the bid, and that relic is on display in the museum today. (Bryan died in 2013.) Rayner gets frustrated when she hears about items that have been discarded by families unaware of the value. To the untrained eye, what appears to be a worthless fragment of metal or canvas may be a piece of American aviation history.

Rayner gets the most satisfaction out of hearing the personal stories associated with the treasures. She tells visitors how the Shenandoah’s captain, Lieutenant Commander Zachary Lansdowne, refused to leave his post during the storm. As the ship began to break up, he realized the control gondola was likely to rip loose from the hull. Lansdowne told the men around him to save themselves, and two men quickly climbed the ladder into the hull to safety. The gondola wrenched loose from the ship and fell to earth, killing Lansdowne and six other men who remained at their posts.

A farmhouse near where the gondola fell is empty today, but still standing. The farmer living there on the morning of the accident set up an aid-station in his kitchen for the airship’s survivors; his back porch served as a makeshift morgue until the coroners arrived.

Since Bryan’s death, Rayner shows the museum by appointment only. She guides visitors to the various wreckage sites, pointing out the hand-carved block of sandstone off Shenandoah Road that marks the exact spot where townspeople recovered Lansdowne’s body. The captain’s U.S. Naval Academy class ring was allegedly found there 12 years after the accident, grown into the stem of a mustard plant. In 1937, the federal government dedicated an impressive granite and bronze memorial in nearby Ava. The once-isolated Neiswonger Farm is now traversed by Interstate 77. Keen-eyed motorists may catch a glimpse of an American flag flying next to a donated sign in a meadow on the west side of the highway near mile-marker 32, a simple reminder of the history that took place there.

In 1991, the Rayners met Peggy Lansdowne Hunt, the daughter of the Shenandoah’s captain, who was visiting Noble County to dedicate a memorial. During Hunt’s visit, the Rayners were able to share their collection with her. “That was a turning point for me,” says Rayner, “meeting someone who was directly affected by this tragedy. It’s one thing to know names, dates, and places. Peggy Lansdowne was just three years old when her father died. That changed her life forever. That’s something you have to factor into history.”

Rayner still hopes for mementos from an event that occurred almost 100 years ago. There may be prizes still packed in an attic, awaiting discovery.