The First Woman to Fly in America

In 1825, a balloonist named “Madame Johnson” took to the skies over New York. Who was she?

:focal(372x240:373x241)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b4/5d/b45d780b-fb4d-4673-896a-8b6e0c7508a5/ascension_de_madame_garnerin_le_28_mars_1802_v2_lib_of_congress.jpg)

On the gusty afternoon of October 20, 1825, a lone balloonist became the first woman to fly in America. Floating over Wall Street’s Coffee House Slip and the one-story villages of Brooklyn, her hydrogen-gas balloon resembled a bobbing top hat to the thousands assembled as it sailed through, in one reporter’s words, “the liquid regions of the sky.” Among the upward-looking throng was an anxious President John Quincy Adams, who days later wrote a sonnet about the flight.

Over the next few years, the press covered three successful ascents and five failed attempts by the balloonist who called herself “Madame Johnson.” There was also a report of a flight over the Mississippi in New Orleans. Interviewed by journalists, Johnson claimed to have flown 32 times from the age of 12. She also said she had flown twice with the first balloonist to make an ascent in America, the Frenchman Jean-Pierre Blanchard.

For all the attention she won for her daring feats, a reporter in 1825 presciently, if somewhat dismissively, noted that soon no one would remember her name. And so it was. “Mysterious” is the word Tom Crouch, an emeritus curator at the National Air and Space Museum and the preeminent historian of ballooning in America, uses to describe Madame Johnson. “Madame J” or “Miss J,” as she was sometimes called, remains largely unknown, even though her place in American aviation history is unassailable.

Fascinated by her story, I searched for Johnson in libraries and archives in France and the United States. Online, I consulted archives in Texas, Louisiana, and Europe. I could not locate a Johnson diary nor any mention of her by fellow aeronauts, as balloonists were then called. But my research turned up a trove of glowing, if inconsistent, newspaper reports and most significantly, her first name—Hannah—mentioned in an 1828 lawsuit pitting “Aeronaut” or “Aerial Voyager” Hannah Johnson against one of New York’s entertainment czars.

Who was she? Some researchers have speculated that she was a circus performer or actress. It’s tantalizing to imagine that Johnson was the American stage name for French-born Éliza Garnerin, a parachutist and equestrian whose father and uncle were well-known aeronauts. Another candidate is Hannah Collier (Collyer) Johnson Franklin de la Rivière. This Hannah, from a wealthy English family, ran away at 15 with the dashing 40-something William Temple Franklin, the illegitimate son of the illegitimate son of American Founding Father and aeronautics promoter Benjamin Franklin. Temple was raised by his famous grandfather and witnessed several early balloon ascensions in France. Yet after his death, Hannah Johnson Franklin, who lived in France, never mentioned aerial pursuits or visits to America in often lengthy notes to her husband’s attorney. Still others have surmised that Madame Johnson may have been Jean-Pierre Blanchard’s daughter. But none of his daughters are known to have survived to adulthood.

Press accounts of the time, without ever giving Madame Johnson’s first name, offered conflicting details: She was identified as European, Parisian, and American; they described her as a widow and the mother of three (or sometimes four) children, one of whom may have been blind. Only one newspaper estimated her age: 35.

What is certain is that the “fair navigator of the clouds” appeared on the New York scene 30 years after Blanchard’s first American flight in 1793. By the 1820s, the skies over Europe and parts of Asia were dotted with festive balloons carrying animals, men, and women, so much so that European audiences had grown weary of them. America’s preeminent traveling balloonist at the time was the French-born “Admiral of Aerology” Guillaume Eugène Robertson, a friend of the Marquis de Lafayette whose showmanship extended to mesmerism and the display of “automatons,” forerunners of today’s robots.

In June 1825, Robertson made two successful flights from Castle Garden, a fort built on an islet off the southern tip of Manhattan. He earned $1,200 for each, equivalent to $31,000 today. Francis Bushnell Fitch, a ferry service owner and a man of “excellent political qualifications,” bought Robertson’s balloon for $700 and set his sights on ramping up the spectacle.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f1/9c/f19c237a-cfec-4f9b-918f-c647a86e2d2f/11h_am2020_castlegarden18483b49658u_live.jpg)

That’s when Madame Johnson arrived on the scene. According to two press accounts, Fitch gave Robertson $200 and asked him to “procure” a female aeronaut. (Women had been flying in France for years.) Robertson, who spoke only French, contacted Johnson but offered her only $50. She declined. He skipped town with the money, according to numerous newspaper reports. Fitch then went directly to Johnson and offered the full $200.

From this interaction, we can glean that Johnson was at least familiar with Robertson, was likely an experienced balloonist, had a strong sense of her own market value, and may have spoken French. Her physiognomy was never commented upon—unusual for the time—but on the day of the flight she was fashionably but unseasonably clad in a white satin dressing gown topped by a short, red, collared jacket. She waved the Bourbon flag of the French monarchy and an American flag to an eager crowd that ranged in estimates from 3,000 to 30,000 in a city of 165,000. Even the contagions of tuberculosis, cholera, and smallpox did not diminish their enthusiasm.

The creation of hydrogen gas for the balloon was a spectacle in itself—a labor-intensive operation requiring large cask cylinders in which sulfuric acid reacted with iron filings and water. Once inflated, the towering sphere created a grand, proto-Vegas extravaganza amidst the stores, banks, residences and churches of lower Manhattan.

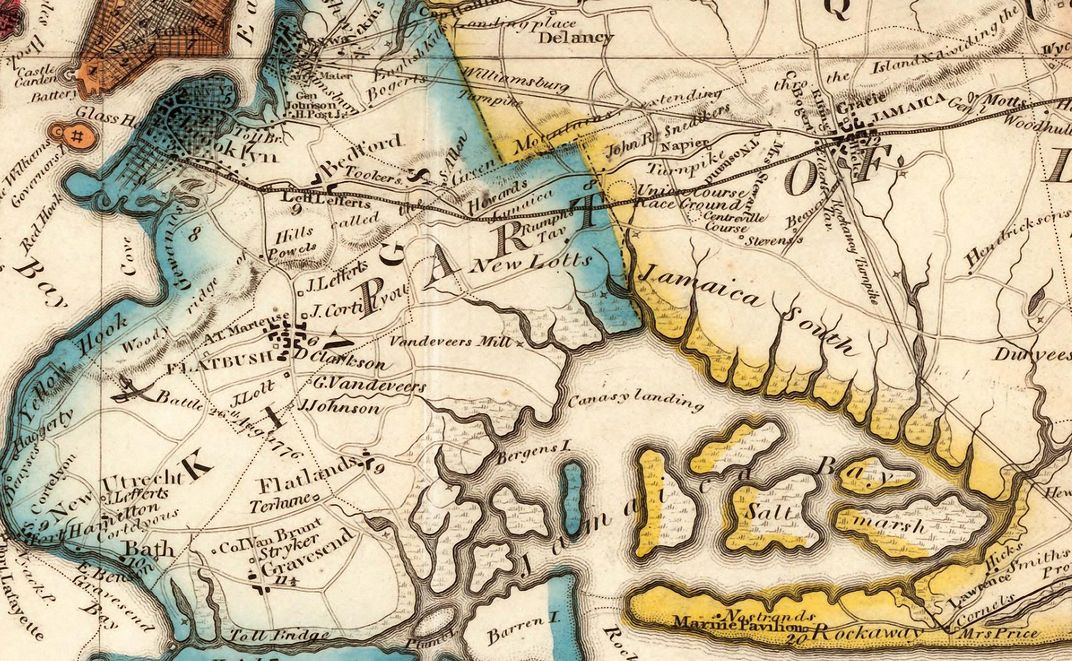

On October 20 at 5 p.m., the “floating bark” was untethered to mounting cheers and began rising rapidly as Madame Johnson threw ballast from the basket. Thousands on Manhattan’s shores and in boats on the river strained eyes skyward searching for a glimpse. Nine miles southeast of Castle Garden, with her balloon drifting over present-day East New York toward Jamaica Bay and the ocean, Johnson tried to land on a hill near a white clapboard steeple located on New Lotts Road. On the ground, a group of Dutch farmers and spectators bird-dogged her descent. She landed in a pond. A young farmer who’d been mowing grass pulled the aeronaut from the water with the help of two workers. Searching frantically for her hat, Johnson voiced concerns about preserving her borrowed balloon and, by one report, flashed a $200 check. After changing from wet clothes at the home of a prominent Dutch family, she was driven in a horse-drawn rig to the lower Brooklyn ferry for the four-cent return to Manhattan.

Back at Castle Garden, Johnson spoke to reporters about her satisfactory command of the balloon, apologized for dropping the American flag, regretted that she had forgotten her barometer, and surmised that she had flown, improbably, five or six miles high. None of the news writers quoted her directly. They relied heavily on balloon puns as well as florid sentiments of relief for her safe return. President Adams, an astronomy buff who had watched some of the first balloon ascents in France, penned a lyrical sonnet about the “sainted seraph, soaring to the skies.”

Fresh from that success, Johnson was invited to perform in the biggest national event of the year, the “Great Celebration,” commemorating the completion of the Erie Canal connecting the Great Lakes with the Hudson River. She was now a star. Stories of her New York flight had been picked up by newspapers in America, Europe, and Australia, describing her as an “angel mind” and a “flyty” enigma.

Then came the Erie Canal flight. It took place—or should have—on Friday, November 4, 1825, from Vauxhall Garden, another popular New York theater-garden. But when Johnson and her gassers were unable to get the balloon to lift off, disgruntled spectators “committed some excesses upon the garden fences and shrubbery.” Nathan Darling, a Vauxhall employee, asserted that the balloon was torn to pieces.

In 1828, Johnson was the chief attraction at an Independence Day celebration at Niblo’s Garden on Broadway. The crowd, estimated between 4,000 and 20,000, spilled out onto the streets and rooftops. Johnson’s “silken bark” twice failed to rise before being released unoccupied to entertain the spectators. Upon hearing that Johnson was not actually in the balloon, “many riotous persons” unleashed their anger on the newly renovated Garden.

It was Johnson’s insistence on full payment, despite the fiasco, that led me to her first name. Niblo refused to pay, and Johnson filed a claim. The lawsuit was simple yet daring: Should a contractor, a woman nonetheless, get paid for her work even though she failed to complete the flight? Johnson charged that Niblo “wholly neglected or refused” to properly prepare the balloon, depriving her of the $300 fee and subsequent flight opportunities. A year later, the judgment was announced. The all-male jury—it would be 108 years before a woman could serve on a New York jury—found in favor of Niblo and, while allowing that Johnson was not in charge of the balloon’s preparation, fined her $95.43.

Johnson made two more solo flights in 1828. In early fall she launched her balloon from a tavern in Kaighns Point, New Jersey. Her last flight, in Philadelphia on October 27, left her badly bruised and with 25 cents after expenses. That Christmas, newspaper reports referred to her sad financial straits and mentioned that she was the mother of four children, three of whom were dependent.

After the jury’s judgment, I could find no other press accounts about the mysterious Madame Johnson. Did she fly again? Resume some other career under a different name? The paper trail vanishes. Perhaps some day another clue will emerge and we’ll learn the ultimate fate of America’s first woman “aerial voyager,” who is as much an enigma today as she was in her own time.