Mystery of the Martian Methane

Curiosity’s failure to find this possible marker of life makes the puzzle more interesting

In 2004 three research groups detected methane gas on Mars, both from Earth observations and from the Mars Express orbiter. The scientific community was ecstatic, because on Earth methane is most commonly seen as an end product of metabolism by methanogenic microbes. Further, methane lasts only about 400 years on Mars, due to the strong ultraviolet flux and the oxidative conditions on the surface—which suggests that the detected methane has been released very recently!

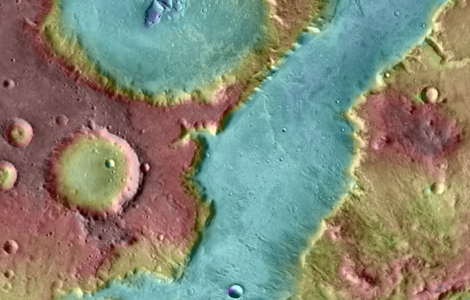

Even more stunning, the spectrometer on Mars Express showed the highest concentrations of methane over areas of high astrobiological interest, such as Nili Fossae, Arabia Terra, and Elysium Planitia. Some of these sites are associated with volcanic activity, where hydrothermal water might percolate up to provide suitable conditions for methanogenic bacteria.

It’s also possible that the methane formed more than four billion years ago, during the Noachian time period when the climate on Mars was warmer and wetter. In that scenario, the methane might preferably be released in spring, when some of the frozen ground thaws, allowing the old methane to bubble up. But the released methane would likely still have originated with early life on Mars. And if life was ever present, it should still be hunkered down on the planet, which is nowadays much colder and dryer. Since methane was detected by three independent research groups, in each case at concentrations of about 10 parts per billion, the findings were considered quite firm.

But, Houston, we have a problem: The Curiosity rover can’t find any methane on Mars; this according to a recent report released by a science team led by Christopher Webster of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The rover drew a blank down to a detection limit of about 1 part per billion.

There could be multiple explanations. One is that the methane is released in hot spot regions such as Nili Fossae, but somehow does not make it to Gale Crater, where the Curiosity rover is located. Due to the generally good mixing of the Martian atmosphere, we would expect a concentration of at least 1 ppb at Gale (equivalent to about 10,000 tons of methane), but there is always the possibility that it does not get there, or that it exists only at tiny concentrations, or that there are some other methane removal mechanisms in the Martian atmosphere that we don’t understand.

Still, the findings put a damper on the search for life on Mars, or at least life that exhales methane. On the positive side, another rover science group led by Laurie Leshin of the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute just found that the Martian soil contains much more water than previously thought—about 1.5 to 3 %—which improves the chances that subsurface life exists, and could make future colonization of Mars easier.

This seems to be the pattern of Mars exploration—alternating optimism and pessimism about the possibility of life on Mars, while the mysteries continue.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Dirk-Schulze-Makuch-headshot.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Dirk-Schulze-Makuch-headshot.jpg)