The (Nail-Biting) First Landing on a Comet

How it went down inside the Rosetta control room that night.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/90/1b/901b4076-b670-43c1-9023-5a89a14708f4/17e_fm2015_paoloferri_live.jpg)

It was three in the morning on November 12—still 9 p.m. the prior night on the U.S. East Coast—when Elsa Montagnon, the night shift flight director of the mission control team, woke me with the news I’d waited more than 10 years to hear: “Philae is GO for landing.” After traveling 6.5 billion kilometers from home, the spacecraft Rosetta was ready to drop our lander Philae onto the surface of comet 67P Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

Arriving at my workstation at the European Space Agency’s space operations center in Darmstadt, Germany, I had my doubts about the “go” decision. Elsa walked me through the details: The Lander Control Centre in Cologne had reported the failure of a small rocket, required to keep Philae pushed against the surface while it anchored itself to the comet with two harpoons. In the near-zero-gravity environment, not having this rocket was troubling, but not part of the go/ no-go criteria that I’d approved as head of mission operations. Now I was wondering if it should have been, but there was little time to think about it. It was time to focus on a critical trajectory correction, diving Rosetta toward the comet and reducing its velocity by 18 centimeters per second. The maneuver went perfectly, but the radio signals telling us it succeeded, traveling at the speed of light like all our communications with Rosetta, took more than 28 minutes to reach us. Twenty-eight minutes is a long time to wait.

A little after 8:30 a.m., our flight dynamics team had measured the Doppler shift of Rosetta’s radio signal and confirmed the landing could proceed. Elsa announced the final “GO” shortly before handing over operations to the day shift, led by Flight Director Andrea Accomazzo, at 9 a.m.

Now only an hour remained until the lander separated from the mothership. We transmitted the command to Rosetta that enabled the lander to take control of its separation and landing activities—another 28-minute journey of a signal across deep space. Now we could only wait and observe.

At 10:02 the telemetry data indicating the separation sequence had begun to reach our consoles. We had just enough time to note the lander cruise locks had been released and all onboard checks had reported success before, at 10:03, the long awaited signal arrived: Separation!

We had feared that as Philae broke away, the sudden 100-kilogram reduction in mass might make Rosetta shake violently. If the oscillations exceeded the thresholds we’d designed, the spacecraft would go into safe mode, shutting down all nonessential systems and correcting itself to a safe attitude.This would interrupt the mission for several hours—and make it impossible for us to establish a radio link with Philae prior to touchdown. This was one of the most critical stages of the entire mission: Failure to separate would end not just Philae’s landing attempt, but possibly Rosetta’s ongoing mission to orbit and observe the comet, too.

But we’d avoided that grim fate, and the mood in the control room was euphoric. I jumped to hug Andrea and Stephan Ulamec, the Lander Project manager. I told Stephan, only half in jest, “The best moment in the mission: We finally got rid of Philae! Now it’s up to your lander to do its job.”

Around noon we received the first telemetry packets from Philae. As they scrolled across my display, I felt overcome with joy. For the last several days I’d told my teams over and over, “Your job is to make sure Philae hits the comet and that we receive and maintain a radio link with it.” Everything else was out of our control: Would Philae survive the touchdown? What would it find on the surface?

We’d done our jobs. Now we could only wait and observe Philae’s five- hour fall toward 67P Churyumov- Gerasimenko.

We gazed in wonder as the pictures that Rosetta and Philae had taken of each other shortly after separation filtered back to us from 300 million miles away—another moving moment. Also a useful one, because it confirmed that Philae’s landing gear had deployed. But now the moment of truth was fast approaching. The control room was nearly silent.

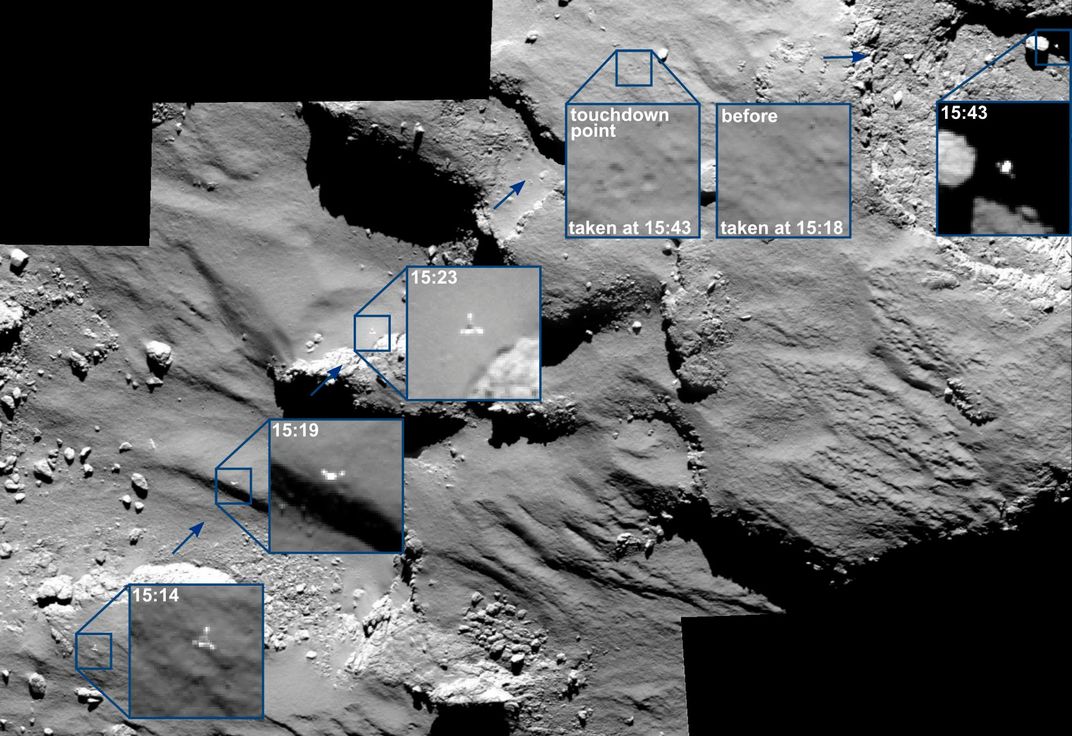

By now we knew the touchdown would come very close to our prediction of 5:03 p.m. Every five to 30 seconds, a new packet of telemetry, sent by Philae and relayed by Rosetta, would scroll across my monitor. Waiting for each packet to confirm that Philae was still alive and talking to us became a gentle torture. At 5:03, Andrea and Stephan shouted confirmation of the touchdown.

I kept my eyes on my display, regarding each new packet as a wonderful gift: Philae was on the surface, and data was still flowing! Knowing now that the data would keep coming, I stood up and hugged any team member I could reach: Andrea, Elsa, Stephan, then everyone in our Flight Control Team. We all had tears in our eyes.

Our excitement was short-lived: Soon after touchdown, the landing center in Cologne said it suspected the harpoons intended to anchor Philae to the surface had not fired. Also, analysis of the solar cells covering the small lander’s surface showed that the current power output was modulated, indicating Philae was still in motion!

Fortunately, Philae’s radio link to Rosetta was still operative. We could see the lander working through its initial scientific measurements. In fact, Philae was working so well it took us some time to accept the landing center’s claim about Philae’s harpoons. It was two hours after touchdown, when the power measurements became more stable, before we were convinced the center was correct: Philae had bounced on the surface before settling in its final position.

Twenty minutes later, the signal stopped. This could mean two things: Either Rosetta was already below the local horizon (possibly behind a rock or a cliff) or Philae had stopped functioning.

This was the first moment after landing when I began to fear Philae’s mission could be already over.

But at approximately 7 a.m., Philae was back, happily talking to us and delivering the measurements it collected during its “night.”

The lander survived 63 hours, 54 of them on the surface, as expected. I spent those 54 hours on the surface with it, sleeping 10 hours in three nights, feeling the same emotions at each new contact. Philae managed to complete its planned tasks: It passed radio waves through 67P for Rosetta to pick up. It analyzed the dust and gas around the comet, and measured the comet’s electrical and thermal properties. It drilled into its surface to attempt collection of a sample.

I was at home when Philae finally went to sleep. When I heard the news, I fell asleep too.