Is There a Doctor with a Phone Onboard?

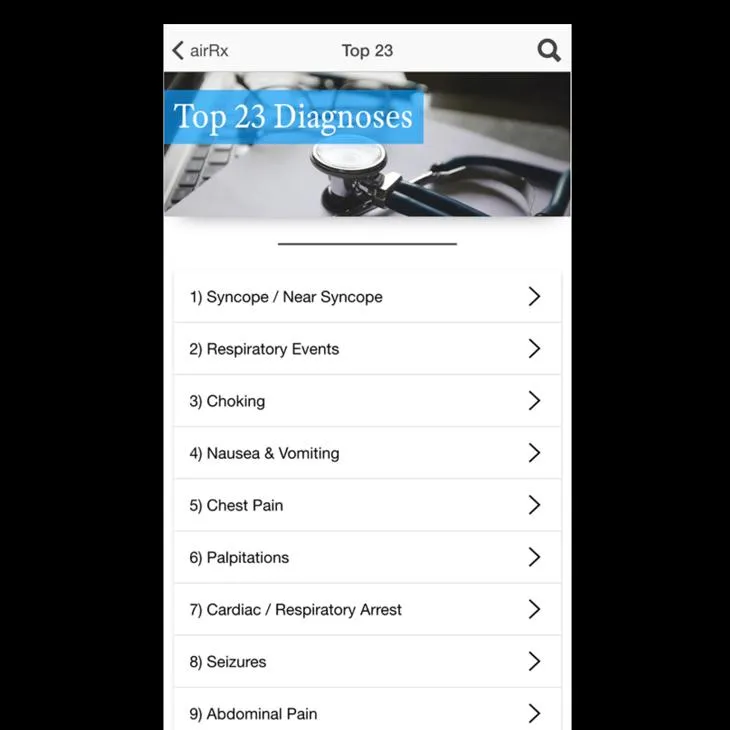

A new smartphone app will give doctors responding to in-flight emergencies basic instructions in how to treat 23 common conditions.

![menu 1[5].jpg](https://th-thumbnailer.cdn-si-edu.com/HUYOrXfXD0PI9K-M5hf9zBapOr4=/1000x750/filters:no_upscale()/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1b/79/1b79aeaf-896c-4466-890e-c709ef8e8cb4/menu_15.jpg)

Raymond Bertino was over the Mediterranean Sea on his way to Athens about a decade ago when he fell ill. “It was the most distressed I’ve ever felt in my life,” he says by phone from his Peoria office. “Frankly, I didn’t know whether I would survive.”

The flight crew asked if there was a physician on board. Bertino could appreciate the irony—he’d been an interventional radiologist for nearly 20 years. (Today, he is Clinical Professor of Radiology and Surgery at the University of Illinois College of Medicine.) Despite having a specialty that, like most medical specialties, rarely involves providing acute, immediate patient care, on three prior flights, he’d been the one to raise his hand to assist a patient.

He recalls that the doctor who came to his aid was an anesthesiologist. Once the flight landed, he was brought to an acute care facility near the airport. “I was pumped full of a liter-and-a-half of IV fluid and I felt better,” Bertino says. He believes he suffered an episode of syncope (fainting caused by a drop in blood pressure), but there’s no way to know for sure.

In 2011, Bertino saw an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association lamenting the lack of standardization and preparation among airline crew to handle in-flight medical crises, and the absence of consistent requirements for reporting them. That’s when he got the inspiration for airRx, a smartphone app that offers doctors instructions on how to handle (initially) 23 common medical conditions until the patient can be delivered to more comprehensive care on the ground. Among the possibilities addressed in the app’s initial release: chest pain, seizures, choking, infectious diseases, and childbirth. It also covers common physiological responses to changes in altitude and cabin pressure.

Bertino developed airRx with five other physicians, including two emergency medicine specialists and two who’ve held various positions specific to aerospace medicine. Because it’s designed to work from a phone set in “Airplane” mode, the content is equivalent to roughly 80 pages of text, Bertino estimates.

The majority of physicians are not emergency room docs, whom Bertino figures is the type best prepared to handle the ambiguity of an acute medical condition manifesting in-flight. He points out that even physicians who complete an Advanced Cardiac Life Support certification annually may feel unprepared to give care on a moment’s notice. “The doctor is probably thinking, ‘My God, I don’t know what to do,’ ” Bertino says. “If it’s outside their scope of practice, it may be something they haven’t had to think about in years.”

Bertino says the majority of physicians caught in this situation will be working outside of their skillset. It seems reasonable to ask, then, if a lay person could use the app to treat someone. “I suspect a nurse or a paramedic could do very well with it,” he says, noting that while some conditions prompt a very simple response, such as laying the patient flat on the floor, most necessitate a more techinical intervention. “I don’t think a lay person would want to try to start an IV,” he says.

The app sells for $4.99 and was made available in the Apple and Android stories at the beginning of summer, though Bertino says he didn’t begin its marketing push until August.

Another area the app covers is what sort of medication and equipment are available on flights operated by carriers of different nationalities. While the FAA requires American carriers to have medical kits and defibrillators on board (and for flight attendants to be certified in Cardio-Pulmonary Resucitation), the tools available tend to vary: As physician Paul Abramson told the New York Times’ Katie Hafner in 2011, “With some planes, it’s a hospital in a box, and they have everything you could ever want. But often they look like they’ve been picked over.”

Bertino says that some other countries require airlines to provide material that the FAA does not require U.S. carriers to keep on board—for example, uterine vasalconstrictors. “If a woman gives birth on a flight, they’re going to have a lot of bleeding,” he says. He says Singapore Airlines and Air India mandate these drugs to be carried on flights, but U.S., Canadian, and European carriers do not.

FAA spokesperson Alison Duquette says the agency does not track in-flight medical emergencies. It last updated its regulations governing what sort of medications and equipment must be available on board in April 2001, when it decreed that automated external defibrillators (AEDs) and enhanced emergency medical kits (EMKs) must be installed on all domestic and international flights within three years. FAA rules do specify the compulsory contents of Emergency Medical Kits, as well as the number of first aid kits to be carried based on the number of passenger seats.