Oldies and Oddities: When Civvies Scrambled Fighters

Neighbors, families, and friends watched the skies for enemy bombers.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/JJ-2011-oldies-and-oddities-FLASH.jpg)

“It may not be a very cheerful thought,” the ominous voice intoned, “but the Reds right now have about a thousand bombers quite capable of destroying 89 cities in one raid…. Won’t you help protect your country, your town, your children?” In the 1950s, that brief radio spot moved hundreds of thousands of American citizens to sign up for the Ground Observer Corps.

In February 1950, six months after the Soviets’ first A-bomb test, the United States was guarded by only a rudimentary radar network. Plans were under way to build radar lines across the continent, but in the meantime America was vulnerable, particularly to attackers sneaking in under radar. Continental Air Command’s Lieutenant General Ennis C. Whitehead revived the civilian Ground Observer Corps, first formed in the wake of the Pearl Harbor attack to watch for Nazi and Japanese aircraft. In June, the outbreak of the Korean War boosted the recruitment effort, and soon over 200,000 people had joined.

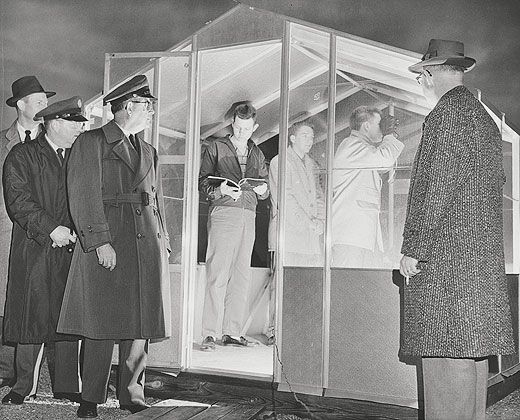

After a few hours of training in aircraft recognition and report filing, observers went on duty at 8,000 observation outposts concentrated along coastal and northern regions. They stood atop buildings, in church bell towers, forest ranger stations, racetrack grandstands—any place with an unobstructed view of the sky.

Each local outpost was connected by telephone to one of 26 filter centers, operated by a joint civilian and Air Force staff. When an observer spotted a potential invader, he or she would call the center with an “aircraft flash,” giving the aircraft’s description, estimated course, speed, and altitude. Usually center staff could use data from civilian flight plans and schedules to identify the bogey, but once in a while a report would be passed upstairs to the nearest Air Defense Direction Center, which would scramble fighters from a nearby air base to investigate.

Sometimes such excitement was aroused not by Soviet aircraft but by unannounced military and civilian flights deliberately flown through observer sectors to test volunteers. Several nationwide drills proved less than impressive, with reports taking upward of 10 minutes to get from outpost to filter center, so in June 1952, the Air Force revamped the program, dubbing it Operation Skywatch. The number of outposts and centers doubled, and a campaign sought to sign up a million new observers.

Skywatch observation posts operated 24/7/365. A training manual noted that anyone “looking for an easy job or with the intention of making anything other than an all-out effort” need not apply. Volunteers received a set of wings and a patch, and by amassing long hours on duty, could earn citations. By the mid-1950s, 400,000 volunteers were working at 16,000 outposts.

Observers were all ages and came from various callings: housewives, TV repairmen, college students, judges. At one point, the outpost in Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey, boasted the oldest volunteer, 86-year-old Calvin W. Miller, and the youngest, seven-year-old second grader Ronnie Barker, who, his father boasted, “can spot and identify the planes a lot quicker than the older folks.”

By the end of the 1950s, detection and defensive technology had outstripped the abilities of observer eyeballs. Distant Early Warning radar appeared in 1957, and SAGE (Semi-Automatic Ground Environment), a network of radar stations under computer control and operated by North American Air Defense Command, took over the watch against bombers and missiles. The Air Force began closing down outposts and took the ground observer corps off 24-hour alert; on January 31, 1959, it was disbanded.

In a letter to the New York Times, Air Force Chief of Information Services Colonel Joseph B. McShane praised the citizens who had given up cookouts and baseball games to man America’s ramparts. They provided, McShane wrote, a “badly needed respite in which to develop more up-to-date and powerful air defense weapons.”