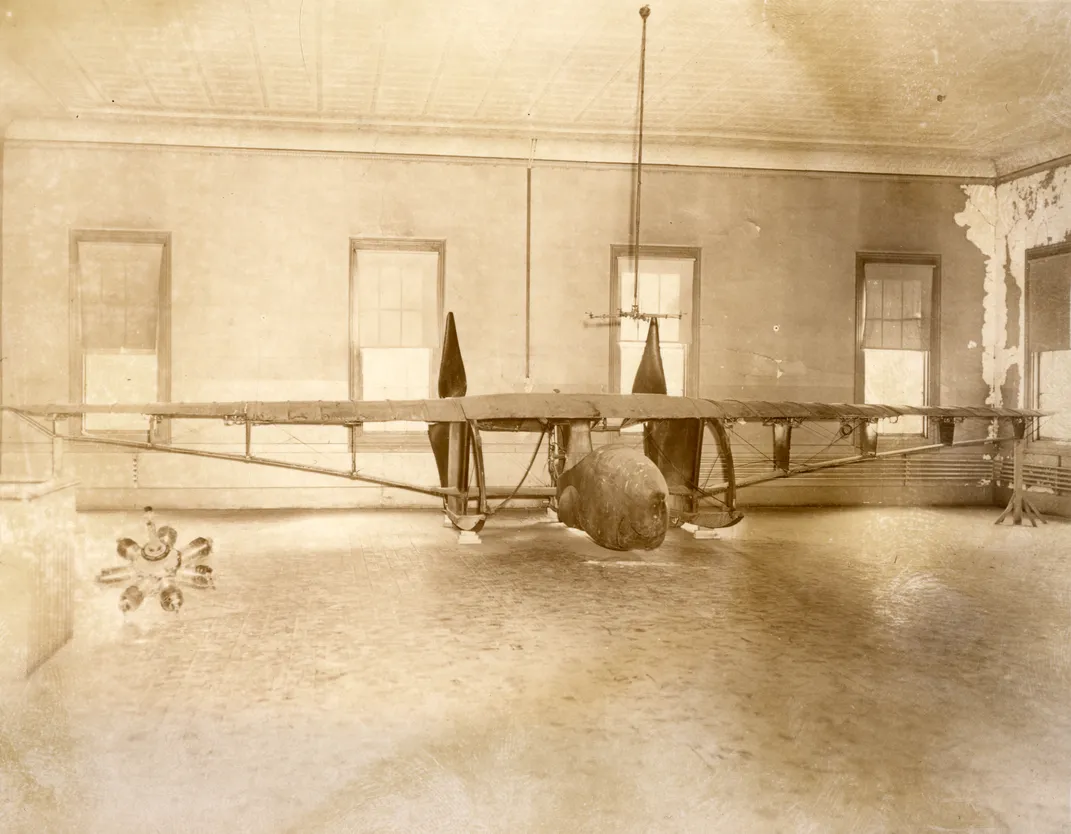

Restoration: The 1912 Olmstead Pusher

A Smithsonian retiree brings a Wright-era airplane back to life.

:focal(1838x2132:1839x2133)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7c/b1/7cb1139d-9cfe-40ed-be7a-8df17a117cf9/16a_fm2019_nasm2018-03358_live.jpg)

Karl Heinzel is fiddling with a C-clamp fastened to a wing of the 1912 Olmsted Pusher so he can mount the wings on what he calls “Frankenstand,” an adjustable support he designed to display the fragile pieces of a century-old aircraft. Designing the display mount is just the latest task in his year-long effort at stabilizing this unusual airplane, one of more than 40 he has worked on during his 34-year career at the National Air and Space Museum. That career was to have ended in 2008, when Heinzel, then deputy shop supervisor, retired at 57. But he has now become that rare person who can legitimately quote Michael Corleone in The Godfather, Part III: “Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in.” Two years after his retirement, “they”—the rare, historic aircraft in the Museum’s collection—pulled him in to continue, unpaid, the work he was paid to do for more than three decades.

It’s hard to imagine Heinzel doing anything other than restoring aircraft. The 67-year-old has been around airplanes “pretty much from day one,” when he was tasked with crawling into the belly of his father’s gull-wing Stinson to retrieve wayward nuts and bolts.

His first restoration was a North American F-86 under the direction of then-lead mechanic Joe Fichera. “He was a no-foolin’-around mechanic,” says Heinzel. “He didn’t tolerate second-rate work.” Fichera’s crew assembled many of the aircraft displayed in the Museum for its 1976 opening on the National Mall. During that period, Heinzel gained experience with everything from pre-World War I aircraft to modern jets. When he returned to the Museum in 2009 it was to help Fichera restore a Curtiss-Wright Junior. (Fichera, who retired in 1984, had returned as a volunteer in 1996.)

But now, nine years into his post-retirement gig, Heinzel’s latest obsession is the unfinished 1912 pusher designed by Charles M. Olmsted, a designer better known for his highly efficient propellers. “Olmsted was way ahead of everybody,” says Heinzel. “His method of construction, the incredibly engineered machinery, the complete weirdness of his aircraft. For 1912? This guy was off the charts.”

Olmsted was a precocious genius. He designed and built his own glider when he was just 13; a year later, in 1895, he made one of the longest gliding flights then flown in the United States. By 1908, he had earned a Ph.D. in astrophysics and was employed at the Mt. Wilson Solar Observatory in Pasadena, California. But he spent much of his time in a shed behind his house, designing his maximum-proficiency propellers.

After three years at the observatory he took a leave of absence in order to set up an aerodynamic laboratory, which paved the way for the formation of the Buffalo-Pitts-Olmsted Syndicate. (Buffalo-Pitts, an agricultural equipment manufacturer, supplied labor and equipment; Olmsted provided the brains.)

Work on the Olmsted Pusher began in 1910, with hundreds of wind tunnel tests. “Just like the Wrights,” says Heinzel, “Olmsted built his own wind tunnel, his own wind tunnel test model, and did all of his own material testing. He was a one-man band. He designed the whole thing, including all the obscurely weird parts. It’s so completely different than anything else.”

Olmsted’s innovations included the airplane’s monocoque fuselage construction, and the ability to vary the curvature of the wing. “I mean, the Wrights had wing-warping,” says Heinzel, “but that was just for roll control. Olmsted’s was for increased lift, low speed, a whole lot of different parameters. He had retractable landing gear for low drag. Compared to this, everybody else was just flying a box kite.”

And, of course, there were his propellers. With a large surface near the blade base and very little surface at the tip, they were unlike any others. The propeller design was eventually used for aircraft setting climb and world weight-carrying records and appeared on the Curtiss NC-4, on the first transatlantic flight. Olmsted deemed them his “secret weapon,” and felt they would add even more interest to his aircraft when it was finally revealed to the public.

Along with such high-tech features were decidedly low-tech ones. The aircraft’s streamlined “boat nose” was designed to absorb a nose-first landing in a plowed field. To facilitate this, the nose wheel was fitted with a football as a shock absorber. “It was a Spalding football,” says Heinzel. “Not a Wilson, not a Rawlings. Spalding.”

In 1912, work on the aircraft came to an abrupt halt when the Buffalo-Pitts Company went bankrupt. Although the aircraft was 90 percent finished, construction was never completed. Olmsted’s laboratory went bankrupt just two years later.

The aircraft languished in the factory for another 20 years. “The plane is still in the loft,” Olmsted’s brother Harold would write years later. “The roof leaks, dust coats everything. Stray workmen steal parts. Specially cut gears of expensive alloys are snitched and sold for junk. The wind tunnel is broken up for lumber, and finally the day arrives when the building is to be torn down. The plane must be removed.”

The original plan had been to remove the shop wall to get the airplane out. Instead, Olmsted had to take a hacksaw to his creation and cut it into several pieces.

The aircraft spent another 13 years in storage at the La Paz Museum in Buffalo, New York, before it was donated to the Smithsonian in 1955.

In 1979, the Pusher made a brief excursion to Purdue University, where it served as a template for the construction of a wind tunnel test model. Tests confirmed that the aircraft was capable of flight. It has been in storage ever since. Now, visitors to the Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center can see the Olmsted Pusher nestled underneath the supersonic Concorde’s vast wingspan. They make an odd couple, but the placement is appropriate: Both aircraft represent some of the most advanced aeronautical concepts of their eras.

“I didn’t come out of retirement just for this aircraft, but it is one that I have always had a fascination with,” says Heinzel. “The whole thing is a work of art.”