Vietnam, the CIA, and the World’s Fastest Aircraft

As the SR-71 went public, these pilots flew its lookalike in secret.

:focal(1399x918:1400x919)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/41/2f/412f342e-793d-4fba-a043-71044b57eac8/03c_on2017_a-12groomlake_live.jpg)

During the selection process for pilots to fly a top-secret mission, Ken Collins was told to report to an apartment in Philadelphia, then locked in a room for six hours in complete darkness. A loudspeaker would periodically order him not to doze off. He didn’t. “I can only assume that I must have passed,” Collins says.

Collins, 88, a retired Air Force colonel, was among six hand-picked Air Force fighter jocks who overflew North Vietnam at Mach 3 on high-altitude photo-reconnaissance missions for the Central Intelligence Agency. He flew a spyplane so hush-hush its operations remained classified for decades. The top-secret project for which Collins had volunteered was code-named Operation Black Shield, and it was based in the Nevada desert. Deceptively nicknamed “Oxcart,” the supersonic Lockheed A-12 aircraft he piloted was the single-seat predecessor of its ultimately more famous, two-man virtual twin, the SR-71 Blackbird.

The A-12 made its first flight in 1962. Lockheed’s Kelly Johnson hadn’t designed the A-12 for Vietnam, but Vietnam was the war it was born into. Johnson had created the airplane in response to the CIA’s need for something that could fly faster and higher than its subsonic U-2, another Johnson-designed reconnaissance airplane, which the agency had relied on since the mid-1950s to provide high-altitude photography. The A-12 was unlike anything anyone had ever seen.

“You didn’t wear it like you did a fighter,” says another pilot who flew Black Shield missions, retired Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Francis J. “Frank” Murray, 86, of Gardnerville, Nevada. “You were stuck way up in the nose, with a monster behind you.”

Finding pilots with the skill and self-possession to ride the monster was no easy task. Those taller than six feet and heavier than 175 pounds were disqualified because of the jet’s particularly cramped cockpit. They had to be between the ages of 25 and 40, and have logged a minimum 2,000 hours of stick time, including considerable experience flying high-performance Century Series aircraft like the McDonnell F-101 Voodoo and Lockheed F-104 Starfighter. The CIA wanted married aviators, who were thought to be more stable than bachelors. Candidates also had to volunteer for a program of which they were told nothing other than that it was space-related, top-secret, and risky.

Collins was no stranger to the danger zone. He’d flown 118 combat missions in Korea, earning a Silver Star, among other decorations. “I had to think about it for about two seconds,” he remembers, “before I said yes.”

In early 1960, about a dozen Air Force pilots, including Collins (Murray would join the program later), made the initial cut and began undergoing intensive physical testing. Their first stop was a week at the Lovelace Clinic in Albuquerque, New Mexico, the same medical facility where John Glenn, Alan Shepard, and other Project Mercury astronauts had survived rigorous physical evaluation the year before. Would-be A-12 drivers were subjected to many of the same assessments. Recalls Collins: “They looked in every orifice we had.”

It was at Lovelace that Collins remembers meeting CIA pilot Francis Gary Powers, whose U-2 would be shot down months later while on a mission over the Soviet Union, underscoring the U-2’s vulnerabilities.

Those who passed muster in New Mexico were sent to the Massachusetts headquarters of the David Clark Company, a leading manufacturer of aviation headsets, NASA pressure suits, and ladies’ undergarments. The pressure suit provided to each pilot was affectionately referred to as “the Bag.” Designed to keep its occupant’s blood from boiling in the thin atmosphere at high altitude, the multi-layered suits were tailor-made. Each pilot was also fitted with an 11-pound, astronaut-style helmet that attached to the pressure suit by a metal ring and was spring-mounted to reduce shoulder fatigue. One would-be A-12 pilot, Collins remembers, was so claustrophobic under the helmet that he washed out of the program.

Mysterious psychological evaluations followed, including polygraph tests and that strange trip to the Philly apartment. Collins says his wife, Jane, was interrogated at length without being given the reasons why. She, too, apparently passed. Eventually, Collins and others chosen for the program were flown to Washington, D.C., and told for the first time they’d be undertaking high-altitude photo missions for the CIA, but they would first have to resign their commissions as military officers. They would be paid $24,000 annually, a bump of a few thousand dollars from their Air Force salaries.

“I did it for the money,” Murray says with a chuckle, “and the thrill.”

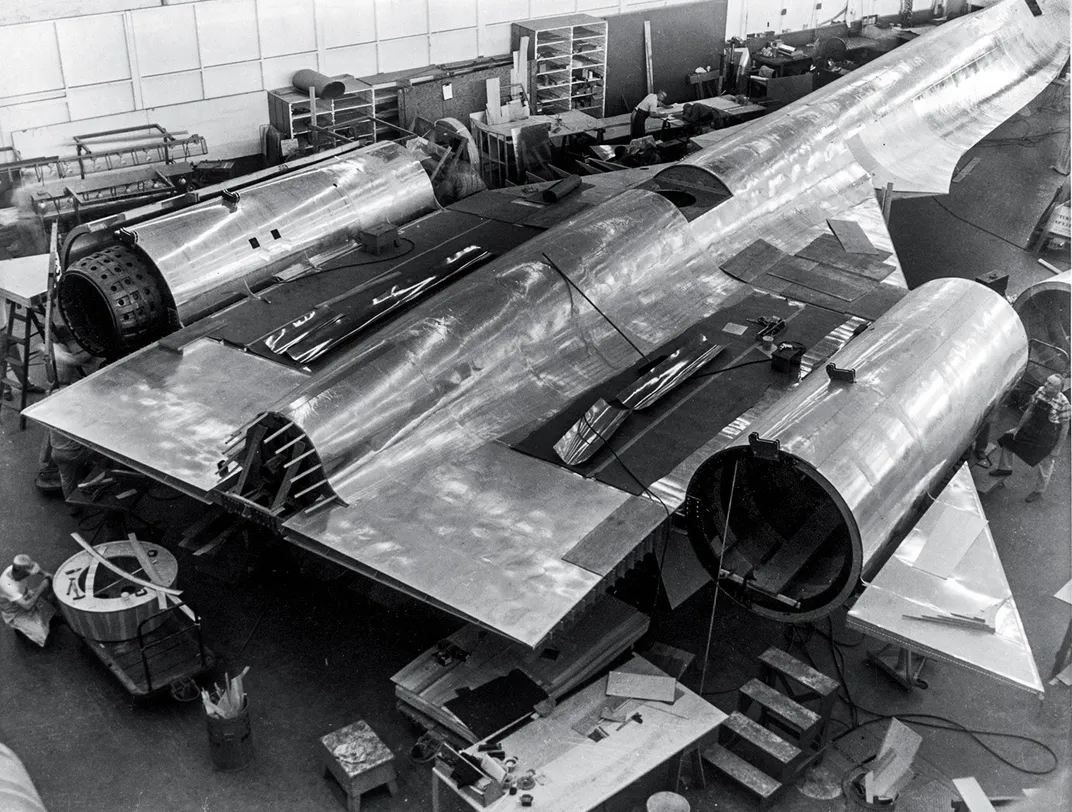

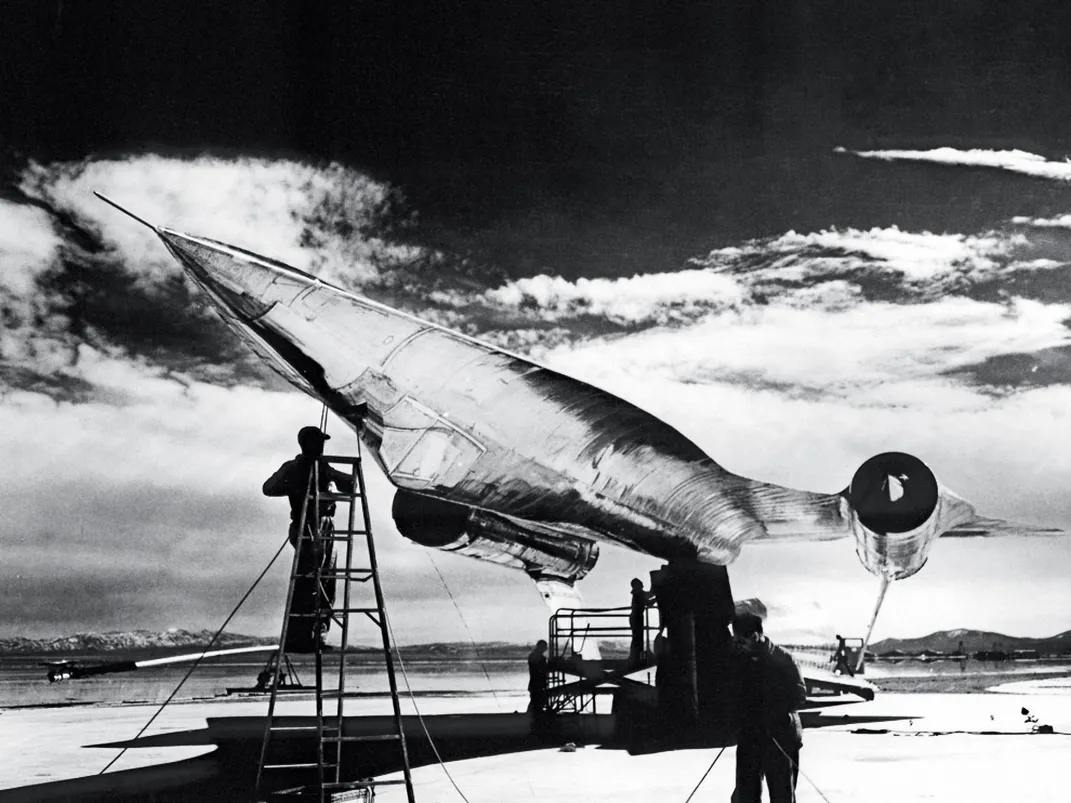

The CIA’s A-12s were based at an Air Force facility 83 miles northwest of Las Vegas: Groom Lake, better known by its map designation, Area 51. Pilots and support personnel simply referred to the facility as “the Area.” They began arriving there in late 1962. Only then were they introduced to the A-12. Collins remembers walking into a darkened hangar as sun rays canted down from the upper windows and being stunned by the sight of the jet. “Its sleek length, the massive twin rudders, and its total blackness,” says Collins. “A vision that will never be forgotten.”

Test flights—ever faster and higher—spanned more than five years. Equipment sometimes malfunctioned, particularly in the aircraft’s wiring systems. Because of how hot the airplane’s skin became at speeds of 2,300 mph, state-of-the-art electrical connectors and components had to be invented to withstand temperatures above 800 degrees Fahrenheit. Pilots, meanwhile, had to withstand the rigors of pushing performance envelopes, and of maintaining secrecy upon returning on weekends to their homes in southern California and what passed for normal family life.

“Nobody knew what we did,” says Collins. “We couldn’t even tell our wives.” Area 51 was never mentioned. To anyone who asked, the pilots and their Air Force-turned-CIA support staff worked as civilian consultants for Hughes Aircraft Company in Culver City, California. Their cover story came replete with a Hughes employee ID and business cards. Printed on the cards was a telephone number to a Hughes secretary, who would politely inform callers that the party they were trying to reach was out of the office and ask them to leave a message. Clandestine behavior became routine.

Perhaps the best example occurred in May 1963, when Collins, while on a low-altitude, subsonic test flight in heavy clouds west of Salt Lake City, watched as his A-12’s airspeed indicator inexplicably began to unwind. Advancing the throttles seemed to have no effect. Suddenly, the nose pitched up and the jet stalled, entering an inverted flat spin. Collins slammed his helmet visor shut, grabbed the D-ring between his legs, pushed his head back against the seat, and punched out. The spurs on his boot heels locked his legs into place, the canopy flew off, and the ejection system performed flawlessly. He parachuted to the ground uninjured.

Figuring he’d be spending a chilly night in the wilds of Utah before help arrived, Collins was gathering up his parachute to use as a blanket when three civilians in a white pickup truck rolled into view. In the bed of the truck was the A-12’s canopy. The men offered him a lift to the spot where they’d observed the aircraft crash and burn. Collins realized the last thing they needed to see up close was the wreckage of a classified aircraft.

“I told them I was flying an F-105 with a nuclear weapon on board,” Collins says with a twinkle in his eye as we sip coffee poolside in his lush backyard. He lives today in the leafy Los Angeles suburb of Woodland Hills. “They didn’t want any part of that, so they drove me at my request to the nearest Utah highway patrol office.”

The office was in Wendover. Collins thanked his rescuers and grabbed his parachute, helmet, and airplane canopy out of the back of the truck. Then he fished a dime out of his survival kit and called Area 51 on a pay phone—collect. Within two hours, a four-engine Lockheed Constellation loaded with security personnel arrived to secure the crash site. Landing soon after the Connie was Kelly Johnson’s personal jet, which flew Collins to the Lovelace Clinic in New Mexico for a medical evaluation. Weeks later, he says, the CIA attempted to hypnotize him, to glean every subconscious detail about the crash that might have been lost from memory as he ejected. When hypnosis didn’t work, Collins says, he went to Lockheed headquarters in Burbank on a Sunday and was injected with sodium pentothal—truth serum. Afterward, “some men in black suits” dropped a woozy Collins back home without offering his wife any explanation about where he’d been.

“She’d thought I’d been drinking,” he says.

The cause of the crash eventually was blamed on the failure of an air data computer and icing that had clogged the jet’s pitot tube, preventing correct information from reaching vital flight instruments.

Collins’ mishap was far from the only one to plague the Oxcart fleet. Of the dozen single-seat A-12s ultimately built, five—including the one Collins had ejected from—would be destroyed. Two A-12 pilots would lose their lives. Despite its unenviable safety record, those who flew the sinister-looking A-12 found it surprisingly docile.

“The thing was fast as a whip and built like a butterfly,” says Murray. “And with that huge wing, the easiest plane I’ve ever landed. The brakes weren’t worth a shit, but we had a 40-foot drag chute, so that helped.”

By summer 1965, with the Vietnam War heating up, U.S. intelligence analysts grew concerned that the North Vietnamese would begin deploying Russian-made SA-2 surface-to-air missiles of the type that had brought down Gary Powers. Declassified records show that on June 3, 1965, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara asked the CIA whether the A-12 could be substituted for the U-2, which, because of its perceived vulnerabilities, was forced to take pictures from well off the enemy coast. The spy agency’s director, Admiral William F. Raborn, said yes—as soon as the A-12s passed final readiness tests. Thus began Operation Black Shield.

The plan called for A-12s and 225 members of the Air Force’s 1129th Special Activities Squadron to be stationed at Kadena, the U.S. military’s sprawling air base on Okinawa. The Department of Defense would spend $3.7 million to build support facilities, including custom hangars, and to establish secure, real-time communications capabilities between the island and CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia. Pilots and support crew would reside about a mile from Kadena in a CIA compound of Quonset huts known as Morgan Manor, and rotate back and forth to Area 51 every six weeks.

On May 31, 1967, following direct authorization from President Lyndon B. Johnson, Black Shield was finally ready to launch its first combat operation. Rain was pouring that day on Okinawa. The A-12 had never flown in heavy precipitation, but the skies over North Vietnam were forecast to be clear—perfect weather for snapping photos. CIA pilot Mele Vojvodich Jr., who would later retire from the Air Force as a major general, taxied out and rocketed into the sky.

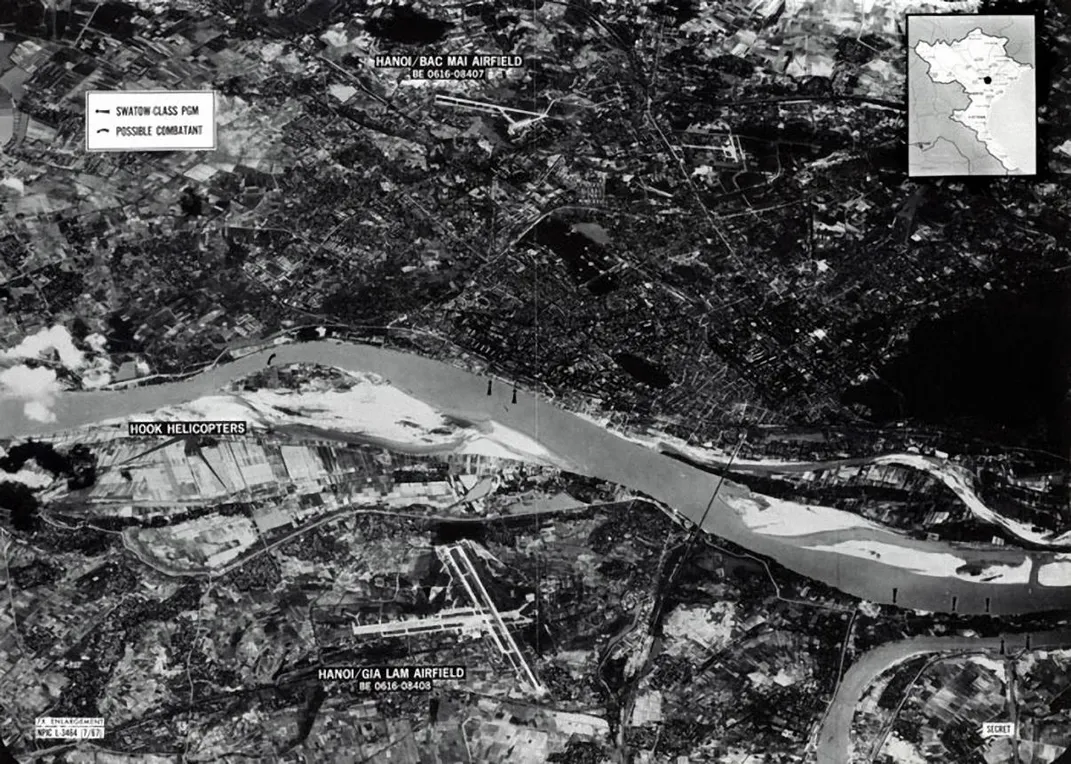

The mission was flown at Mach 3.1 and 80,000 feet. Vojvodich made one pass over North Vietnam, turned, and made another, photographing 70 of 190 possible anti-aircraft-missile sites, as well as nine unspecified “priority” targets. Three hours and 39 minutes later, he was back safely on Okinawa. The A-12’s radar-detecting gear showed that the airplane had passed high over enemy turf unnoticed.

But anonymity didn’t last long. Soon, North Vietnamese Fan Song ground control radar operators began tracking Black Shield flights and sometimes lobbing SA-2s at them. “They’d come up to about 70,000 feet, then fall off,” Collins says. “It would definitely get your attention.”

A typical Black Shield mission began more than a day before launch, when Langley would alert commanders on Okinawa that fresh photographs of specific locations were needed. Mission planners, including Ron Girard, a B-52 navigator-turned-CIA employee, would begin putting together a route map, cutting up aeronautical charts and gluing them into a continuous strip more than 50 feet long. “We went through gallons and gallons of rubber cement,” says Girard.

The strip was photographed, then rolled up and fed through a periscopic viewer the pilot could access inside the A-12’s cockpit. The aircraft’s navigation system automatically guided the aircraft and activated cameras.

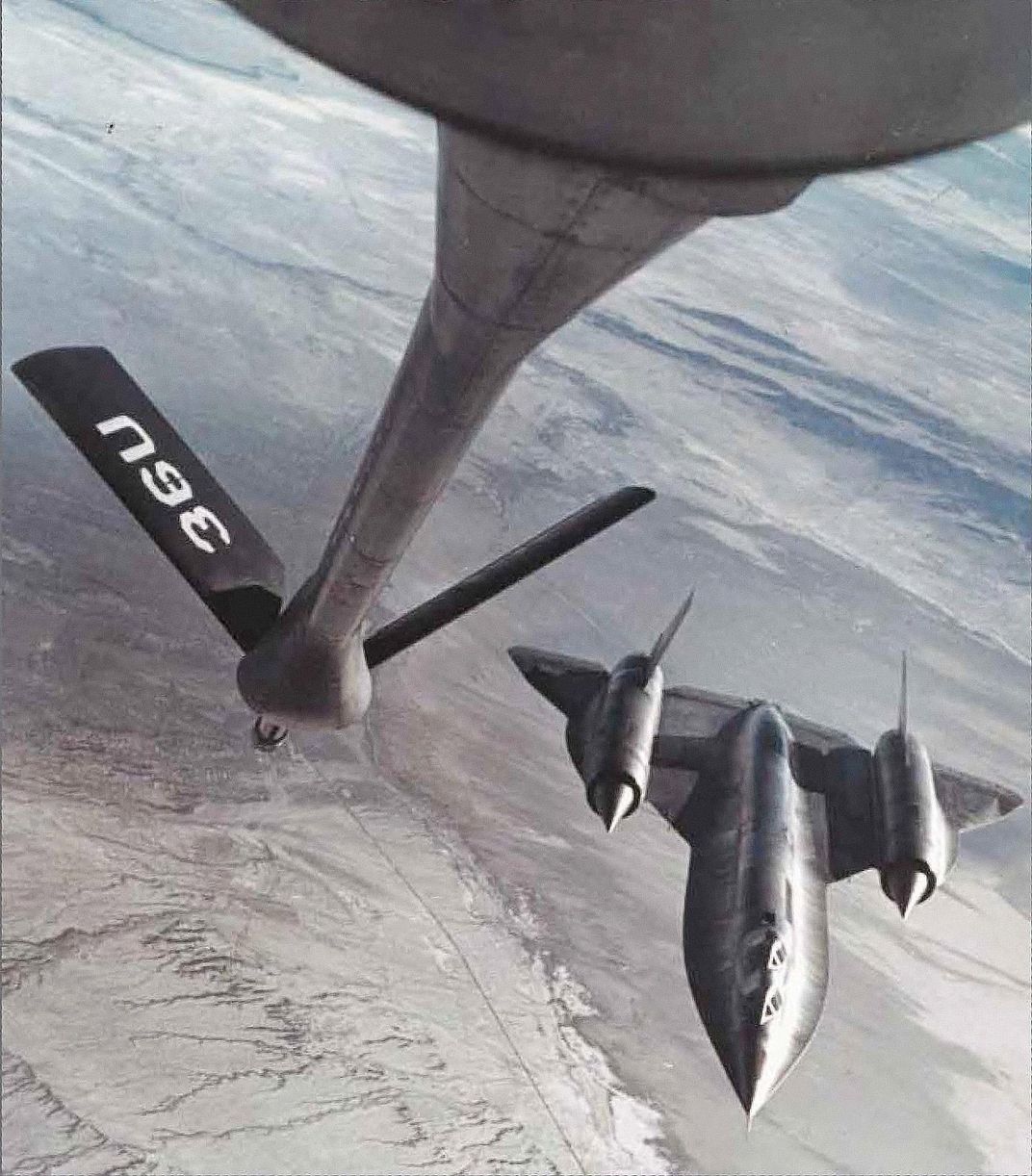

For each mission, two A-12s and two pilots were readied. Two hours before takeoff, both pilots would undergo medical exams, then suit up. If the primary aircraft and driver were deemed good to go and weather forecasts over the target area were favorable, the backup pilot and aircraft stood down. Then it was wheels up and off to get gas. South of Okinawa, the jet would link up with an Air Force KC-135Q whose plumbing was engineered to accommodate the specially refined, high-flashpoint JP-7 fuel the A-12 required. The aircraft was then ready to head to North Vietnam. (After it exited hostile airspace, a second tanker would be waiting over Thailand to refuel the aircraft.)

Busy as A-12 pilots were in the cockpit—managing temperatures, responding to enemy missile sensor alerts, and refueling—Black Shield flights were, they say, largely uneventful. Most of each mission was spent with the aircraft on autopilot while maintaining total radio silence.

Upon landing back in Okinawa, the film from the cameras was quickly removed and flown on special Air Force transports to Eastman Kodak’s corporate headquarters in Rochester, New York. After U.S. commanders in South Vietnam complained about the time lag for actionable photo-intelligence, the film was delivered to an Air Force lab in Japan that offered 24-hour turnaround.

When North Korean forces captured the USS Pueblo, a Navy intelligence-gathering ship, Black Shield A-12s were tasked in late January 1968 with locating the vessel and determining the extent of any associated North Korean military buildup. It took pilot Jack Weeks one flight to find the Pueblo, which was anchored outside the port city of Wonsan. Frank Murray flew a second reconnaissance mission about two weeks later, making two passes over North Korea. Neither Murray nor Weeks was shot at.

By June 1968, with a mere one year in service and all of 29 missions logged, Black Shield was abruptly canceled and the A-12 retired, replaced by the SR-71. At the time, the single-seat A-12 could fly slightly higher and faster than the two-seat SR-71, but the Blackbirds offered greater range, more versatile sensor loads, and better electronic countermeasures. The CIA had further concluded that the Oxcart lacked the quick-response capability of the U-2 it was designed to replace. U-2s could execute strategic intelligence missions with far fewer logistical considerations and one-third the support personnel.

Collins, however, believes the A-12 fell victim to a turf war between the Air Force and the CIA. “What I was told at the time,” he says, “is that the Air Force flies airplanes, not the CIA, and the A-12 was the CIA’s plane.”

Whatever the reason, the Black Shield program would end on a tragic note the month it was canceled when an A-12 flown by Jack Weeks apparently suffered a catastrophic engine failure and disappeared somewhere near the Philippines. No trace of pilot or airplane has ever been found.

Frank Murray, who flew four Black Shield A-12 missions, turned down the CIA’s offer to fly U-2s. “Those poor guys were flying missions that were eight, ten hours, and my bones couldn’t stand sitting that long,” he says. He would return to the Air Force and Vietnam, escorting search-and-rescue helicopters in a propeller-driven Douglas A-1 Skyraider. The unexpected trajectory of his flying career—switching from the U.S. military’s fastest airplane to among its slowest—is not lost on him. “A great change of pace,” he laughs today.

Ken Collins would also return to uniform, flying Air Force SR-71s. Before retiring in 1980, he would log 350 hours in the Blackbird, five less than he did in the A-12. His half-dozen Black Shield missions were the most flown by any of the six pilots who steered A-12s over North Vietnam.

A few weeks after Black Shield ended, all five of its surviving pilots quietly assembled at Area 51, along with Jack Weeks’ widow. Each was presented with the CIA’s Intelligence Star for valor. The pilots’ wives also attended the ceremony and got to see for the first time the airplane their husbands had been flying, but they weren’t allowed to tell anyone about it. Until 1998, Black Shield would remain classified. Some details about the program still are.

All seven surviving single-seat A-12s are scattered on public display across the United States. One rests on the flight deck of the USS Intrepid museum at a seaport in lower Manhattan. Another stands watch over CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia.