Or Die Trying

After the Wright brothers flew, a handful of inventors were determined to join them.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Or-Die-Trying-Flash.jpg)

Earle Ovington meant well. “It is a peculiar fact, but nevertheless true that a man seems to think that he is able, or competent rather, to design an aeroplane, whether he knows anything about the principles underlying aerodynamics or not,” he wrote in the October 1912 issue of Aeronautics. His advice was simple: “You should lay a firm foundation before you attempt to enter practical work.” Ovington could speak with authority. He was once an assistant to Thomas Edison, and had learned to fly at Louis Blériot’s school in France. “If by writing this article I can save just one misguided inventor from the certain failure which is awaiting him,” he wrote, “I will consider that my time has not been spent in vain.”

Ovington had reason to be concerned. For every Wilbur Wright, Glenn Curtiss, or Alberto Santos-Dumont, there were plenty of Lyman Gilmores (more about him soon). Many would-be airplane inventors had visions that far surpassed their engineering competence. Fate caught others faster than their luck could hold. Some actually did the hard work and flew—but only into dead ends. They all possessed insatiable curiosity, imagination, and persistence—almost all of the ingredients needed for success.

The Unrealized Visionaries

Aeronautical innovation is ultimately collaborative. But some pioneers held fast to their own theories, resulting in grand claims backed by few accomplishments.

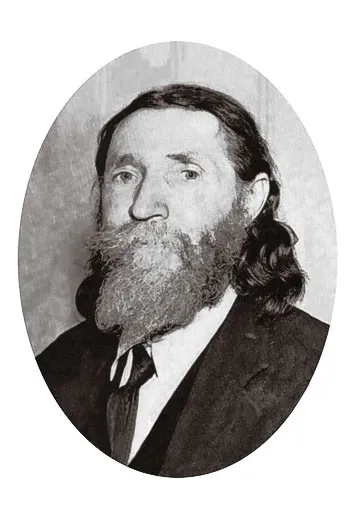

Lyman Gilmore

The sometime gold prospector was the archetypal old man of the mountain: scraggly beard, long hair, and wizened face. Driven by a vision, he flew in the hills near Grass Valley, California—if you believed him.

According to Gilmore, his inspiration came from a poem he’d read as a high school student: It spoke of “robbing from the eagle his eagle’s secret.” In 1894, Gilmore claimed to have built a glider with an 18-foot wingspan and to have flown in it down a hill, towed by a horse. If true, it would have been a remarkable achievement. But there’s no evidence of Gilmore’s glider other than his word and the shaky recollections of his family. How could Gilmore have learned what he needed to create a glider while isolated in California’s gold mining country? It’s possible he could have read Progress in Flying Machines, published that year by French-born American engineer and aviation enthusiast Octave Chanute, or a newspaper article on German glider expert Otto Lilienthal. Whatever the case, Gilmore wanted to fly something.

In 1898, he produced a drawing depicting a powered monoplane and had it signed by witnesses. In 1902, he claimed a successful powered flight. Between 1905 and 1907, he opened the Lyman Gilmore Aerodrome in Grass Valley and began selling stock in the first of several aircraft companies he founded based on his 1898 design. Newspaper stories from 1909 describe a failed attempt to fly at the California State Fair. In 1912, Gilmore revealed a two-person monoplane by driving the machine around his field for hours until it fell over. But again, there is no evidence of a Gilmore machine in the air.

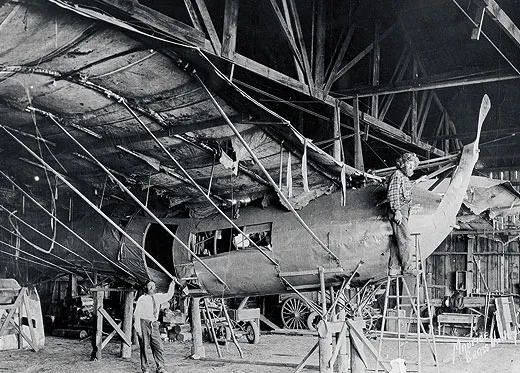

There is evidence that he built them: A film, shot sometime in the 1930s, shows a giant monoplane with a torpedo-shaped fuselage in Gilmore’s barn. It looks vaguely like his 1898 design. The propeller swings listlessly. The wings are tattered. We see Gilmore and his brother up close, in rumpled clothes and with long hair and beards, sweeping clouds of dust from the fuselage and displaying page after page of blueprints. Finally, they clamber up a ladder with one of two dogs, get inside the airplane, and stare out from the windows.

The airplane was ambitious: a passenger-carrying tractor monoplane. But Gilmore was not the first to have the idea. Alphonse Pénaud and William Henson (to name two) pre-dated him by decades. Although Gilmore clearly built something, created an airfield, and forayed into business, he never ventured beyond his own aeronautic back yard. When he finally flew in 1924, he was a passenger.

In 1935, a fire destroyed his barn and any proof of flight it might have contained. He died in 1951. Other than his grandiose aeronautical dreams, Lyman Gilmore was a modest man. His ideas never hurt anyone. The same could not be said of William Christmas.

William Christmas

No one tells this story better than William Christmas himself. Writing to the U.S. Air Force’s General Carl Spaatz on September 25, 1947, Christmas laid out his credentials. “My basic discoveries and inventions has [sic] made the aviation industry what it is today.” He claimed sole credit for the aileron, “the most important invention in aviation,” among 400 other inventions. After declaring that “the present design of planes is ALL WRONG,” he finally got to his request, which was to be commissioned by the Air Force “to design the FASTEST PLANE in the world.” His justification was that he’d done it before, in 1918, with the Christmas Bullet. (He did not reveal that each time it had flown, the pilot had been killed.)

Born in 1865 in North Carolina, Christmas came to Washington, D.C., to conclude his medical studies. He became fascinated with flight, and said he learned everything he needed to know from the study of birds. On March 6, 1908, according to Christmas and several witnesses, he flew a powered machine in Falls Church, Virginia. He formed the Christmas Aeroplane Company in 1910. A year later, one of his designs flew in College Park, Maryland, and in 1912, he exhibited at the New York Aero Show.

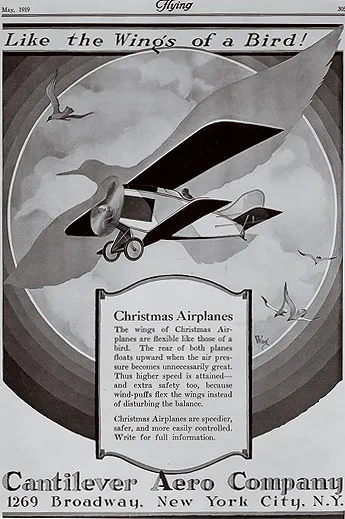

After proposing a giant bomber to the military in 1915, Christmas began work on the Bullet. He was convinced that his revolutionary “flexible wing” concept would result in the fastest aircraft ever built. The wing spars were made from “sawmill blade steel” and designed to flex upward the faster the airplane went. With thoroughly convinced investors behind him, Christmas negotiated a contract with Continental Aircraft to manufacture two airplanes. Ignoring the concerns of the Continental engineers, Christmas authorized two test flights; in both, the wings failed. Pilot Cuthbert Mills landed hard and was burned to death. Allington Jolly spun in when the wing twisted off; he also died. Christmas blamed the pilots and unnamed saboteurs.

Was Christmas ever ahead of his time? He insisted that he was the sole authority for his concepts, which were similar to those of the leading designers. The Bullet roughly resembles the Dayton-Wright RB-1 racer—an airplane widely considered revolutionary—which flew two years later. He proposed the gigantic Christmas Supertransport passenger airplane, which was not unlike those actually flown by Hugo Junkers and other contemporaries. After the Bullet, none of Christmas’ airplanes was ever built.

Still, his claims of supreme aeronautical achievement got him attention. By 1942, the Supertransport had morphed into the 200,000-pound, all-wood Christmas Battleplane. Following a letter from Christmas, U.S. Senator Robert Reynolds of North Carolina directed George Lewis of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) to conduct wind tunnel tests and begin production. When Lewis replied that it would take 1,000 engineers a year and a half to develop a prototype in the middle of a war, Reynolds backed away. Christmas did not.

His 1947 letter to Spaatz was typical. The “fastest plane” he proposed would indeed be fast: Mach 0.92. Three weeks from the letter’s date, Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier. Christmas died in 1960 at the age of 95, still predicting the future, still making claims.

The Doomed Enthusiasts

Watching the Wrights fly must have been like watching Fred Astaire dance. Their seemingly effortless grace masked their discipline, caution, and skill. Respect for undiscovered aerial hazards led them through a progression of experiments and kept them alive. Many of the aviators who tried to copy them fell victim to the anxious rush to fulfill a dream.

Addison Vespucius Hartle

Perhaps his middle name had something to do with it. Hartle was born in 1886, and back then, Vespucius was an unusual, but not unheard of, boys’ name. It is the Latinized version of Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci’s last name. For Vespucci, it was all about heading west. In 1911, so did Hartle, leaving his hometown of Marseilles, Ohio, in search of flight.

Hartle was used to forging his own way. When he was 15 years old, his parents died of pneumonia within three days of each other. He and his eight siblings were divided up to live with various relatives. At age 21, Hartle set out to make his way in the world. Tall, uncommonly strong, temperate, and good-natured, he held a variety of jobs: selling laundry bluing, then Christmas cards; sheet metal roofer. He could afford to pick and choose: He and his siblings had inherited their parents’ modest fortune. He was mechanically curious, owning the first car in Marseilles.

In early 1911, Hartle moved to Los Angeles. Besides being the home of his sister, Anna, Los Angeles had an active aviation scene. An air meet held at Dominguez Field in January 1910 had attracted the luminaries of the day: Curtiss, Louis Paulhan, Roy Knabenshue, Lincoln Beachey, Walter Brookins, and Arch Hoxsey. Hartle quickly found Harry Dosh, who, with six “Curtiss-type” airplanes to his name, was already a veteran airplane builder. Hartle spent $1,500 to commission a large machine. Immediately after it was finished, he took it to Dominguez Field.

Forgoing any initial “grass-cutting” practice, Hartle made his first flight on May 16, 1911, and for a completely untrained pilot, it was an incredible success: a distance of three miles, full circles, and an altitude of more than 100 feet. He wrote about it that evening to a friend in Ohio: “Reached an altitude of about 125 feet and controlled the machine perfectly. Shall do better tomorrow, that is, I think I shall, and you know that helps a little…. Yours in a hurry, ADDISON V. HARTLE.”

The next morning he returned to Dominguez Field with his sister. After another successful flight, he announced his intention to fly a figure eight. Within a few moments of taking off, it was clear that the left aileron had come loose: It was flapping uselessly at the end of a control wire. The crowd waved frantically for him to come down, and he appeared to heed the warning. But just as he neared the ground, he pulled back, rose, and began a figure eight. The airplane lurched over on its side and plummeted to the ground. Hartle was thrown forward. The airplane flipped and landed on top of him. He never had a chance. Anna collapsed as they dragged him out of the wreckage, still breathing. He died about 15 minutes later.

His body was returned to Ohio with his traumatized sister. Dosh determined that the aileron had come loose because Hartle had failed to solder a pin holding it in place. Hartle was one of the first amateur aviators to lose his life in a crash. (He was also one of the first to be insured.)

Leonard Bonney

Leonard Bonney decided to go to the Wright School to learn to fly. On May 7, 1911, Orville Wright wrote about Bonney to his brother Wilbur: “Bonney is the most hopeful of our newer men. He is a good worker and enthusiastic. He weighs 125 lbs., and will make a good racer.” Bonney became a member of the Wright’s exhibition team for a few months, flying three engagements before the team was dissolved (see “Ladies and Gentlemen, The Aeroplane!” Apr./May 2008).

He continued with exhibition flying for a short time, including a 112-mile flight from Los Angeles to San Diego with a passenger. He then began a career as an instructor, flying for the Sloan, Moisant, and Curtiss schools, and as a civilian for the U.S. Army during World War I. When the war ended, Bonney, at age 32, retired from flying. He held a title many early birds coveted: survivor.

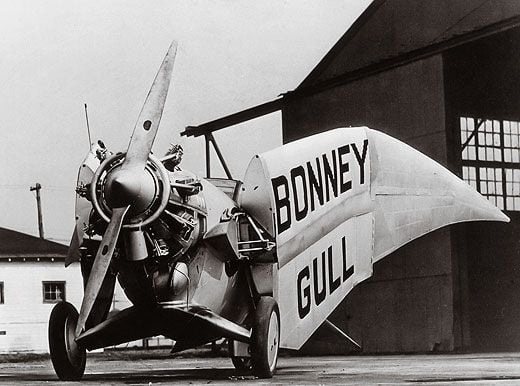

His retirement, however, did not hold. Ten years later, after marrying, succeeding in business, and settling in Flushing, New York, Bonney returned to homemade aviation. Like Christmas, he studied birds, gulls in particular. Convinced their unique shape held aerodynamic advantages, he began to fashion an airplane. By the spring of 1928, with his own funds, he had designed, built, and wind-tunnel-tested the all-metal manifestation of his dream: the Bonney Gull.

Looking at the dozen or so existing photographs of the machine is like seeing a friend’s unfortunate new hairstyle: You feel awe at the audacity, coupled with worry for the owner’s future. Despite several advanced features, the awkwardness of the Gull’s wings and fuselage, bulbous canopy, fish-like rudder, and avian elevator did not inspire confidence.

Like Gilmore and his monoplane, Bonney and his Gull were captured on film. On May 4, 1928, at New York’s Curtiss Field, he showed the machine off for newsreel cameras. We can see that the Gull is clearly a source of great pride as Bonney, looking older than his 42 years, sits in the cockpit and demonstrates the controls. Soon the Gull starts its only takeoff run and, with an ungainly bounce, begins to climb. You can’t see it in the film, but Bonney began to wave to his wife. At seven seconds into the flight, the Gull suddenly pitches forward. An onlooker, perhaps a reporter, inadvertently steps in front of the camera and we’re spared seeing the Gull plunge into the ground.

Soon after he arrived at the hospital, Bonney died. In the announcement for his funeral, the New York Times reported that when he had ordered the airplane onto the field the day before, his friends, as they had for weeks, “protested against him flying it.” Bonney laughed.

The Successful Dead Ends

Henry Walden and Frank Bolden braved the new world of powered flight by copying no one. They were methodical, creative, and industrious. They made no wild claims. They created truly original designs that flew well—not once, but many times, and professionally. Earle Ovington would have approved.

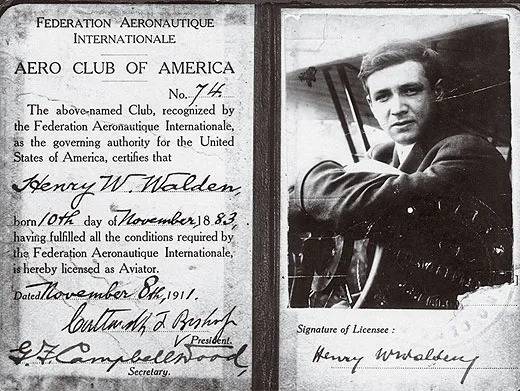

Henry Walden

Henry Walden’s first experience with flight was watching someone get killed. In 1890, at age seven, Walden was living in Romania, where his father worked as a civil engineer. While at a fair, Walden witnessed a balloonist crash into a church wall. He later wrote that the incident “left a lasting impression.”

Forced to become a dentist by his parents, Walden, who then lived in New York City, became a member of the Aeronautic Society of New York, which was then meeting at the Morris Park racetrack in the Bronx. The group could boast of few successes. Descriptions of the members’ experiments included words like “tree” and “fence,” coupled with “plunged” and “smashed.” Still, Walden was entranced, and he began inventing machines. He immediately failed.

His Walden I and II machines of early 1909 never left the ground. The first was a strange tandem-wing design, whose 500-pound engine kept it pinned to Earth. The Walden II was also odd, with its engine turning around the crankshaft and slung like a pendulum for stability. After some taxi tests, Walden planned to make a first flight, but the night before, he left the aircraft outside, and a storm mercifully destroyed it. Walden assessed his work and came to a conclusion: “Freak designs must be avoided.”

His breakthrough was the Walden III. After building a rudimentary wind tunnel and experimenting with different surface designs, Walden settled on the still-unusual monoplane (biplanes dominated the industry). On December 9, 1909, the airplane was ready to test. At Mineola, Long Island, Walden left the ground and flew for a few hundred feet. He put the aircraft back down safely—elated.

By September 1911, Walden had created the Walden IX, a refinement of his monoplane design. He had incorporated a company with George Dyott, taken on students and investors, and begun flying competitively. The 1911 Brighton Beach Air Meet attracted the stars of the aviation world: Claude Grahame-White, Tom Sopwith, Harry Atwood, Eugene Ely—and Walden. He was not the best pilot, nor did he have the best airplane. But while he was in the air, the crowd was informed that he was flying an American-designed monoplane, and that he was the only designer-builder-aviator in attendance. He landed to a hero’s welcome, and quickly amassed a busy schedule of performances around the country.

But his successes never matured into a lucrative career, nor created a lasting influence on aircraft design. The Blériot and Deperdussin designs of 1909 through 1912 were the true forerunners of the modern monoplane.

Walden continued in the flying business until the Great Depression, starting two research companies, developing a radio-controlled missile, amassing more than 50 patents, and losing “two sizable fortunes.” Fortunately, the dental practice never closed. He died in 1964, having once described himself as “rich only in the satisfaction of a life thoroughly lived.”

Frank Boland

Just like the Wrights and Curtiss, Frank Boland and his brothers could trace their aviation business to their bicycle shop. The three brothers made a great team: Frank was the enthusiast, Joseph the engineer, and James the businessman. What began in the 1890s as a backyard business in Rahway, New Jersey, expanded into motorcycles, then automobiles, and in 1907, airplanes. The first Boland aircraft, a tractor monoplane with Joseph’s promising 60-horsepower V-8 engine, failed.

The brothers tried again in 1909, purchasing from William Greene a Curtiss-inspired biplane he had built. Frank removed the tail and installed what they hoped would be a revolutionary set of control surfaces, which they called jibs. Like all would-be aircraft designers of the time, the Bolands had to face the Wright brothers’ wing-warping/lateral control patent. There were three choices: pay the Wrights royalties, build an infringing machine and risk a lawsuit, or create something that achieved lateral control without infringing the patent. Few took the first choice. Curtiss (and those who built Curtiss-types) chose the second, leading to epic court battles with the Wrights. With the jib design, the Bolands took the third route—and succeeded. But not at first.

On his first and second flights, Frank hit the same tree. But his third flight, in late November, with Joseph as passenger, was a success. It was the first flight in New Jersey. The flying continued, as did their growing engine business. Their first original airplane, the Boland Tailless, appeared in the spring of 1910. By October 1911, Frank was making demonstration flights. According to a biography of Boland by Harold Morehouse, Wilbur Wright himself inspected the machine and its jib controls and pronounced it not only non-infringing, but also capable of making the tightest turns he’d ever seen.

The lack of a tail, however, made the aircraft look decidedly strange. And the pilot’s position was positively bizarre: Sitting suspended inside a framework between the airplane’s forward canard and the wings, with his legs spread out in front of him, the pilot looked like a victim of the Spanish Inquisition. But the arrangement worked, and the Bolands were in business.

Here, too, they were unconventional. Partnering with a promoter named Fausto Rodriguez, Frank made arrangements for a tour of Central and South America in the fall and winter of 1912. After several successful flights in Venezuela, the tour moved on to Trinidad. On January 23, 1913, Frank made a special exhibition flight for the governor in Port of Spain. As he came in to land, the machine suddenly and unexplainably dove into the ground. The impact threw Boland out of the machine. He was killed instantly.

Joseph and James continued the business. Four months later, a new Boland tailless appeared in Aeronautics magazine. But on the very next page, an article on the new Burgess flying boat pointed the way to the Bolands’ future. Spurred on by investor Inglis Moore Uppercu, a wealthy New York Cadillac dealer, the Boland Company was reorganized as the Aeromarine Plane and Motor Company and focused almost exclusively on flying boats. Frank’s tailless design was left behind.

Epilogue

On April 19, 1912, the Elbridge Engine Company received a letter from another homegrown aeronautical engineer. It began: “A little over a year ago I spent $5,000 for a monoplane and I was unable to make a really successful flight. To cap the climax I had a fall of 75 or 80 feet. Busted physically and financially, I spent the winter making a machine, and a real flier it has proved to be.” It was signed by one of the lucky ones: Clyde Cessna.

Paul Glenshaw is director of the Discovery of Flight Foundation and co-producer of the 2009 documentary Barnstorming.