Panthers at Sea

U.S. Navy Panthers weren’t highly evolved, but they could shoot. And they were air conditioned.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Panthers-At-Sea-631-edit.jpg)

The U.S. Navy was late to the revolution. The Army Air Forces put in an order for its first jet, the Bell XP-59, before the U.S. entered World War II. The Royal Air Force used the jet-powered Gloster Meteor against buzz bombs in July 1944, and the Luftwaffe was well under way; in July of that year, its Me 262 was already shooting down Allied fighters. But air forces have long runways on which to land fast, unproved airplanes. For the Navy, with its peculiar habit of landing aircraft on ships, the transition to jet aircraft was more hazardous and therefore slower. The service wouldn’t field its first operational jet, the McDonnell FH-1 Phantom, until 1947.

Two more jets entered the Navy fleet before the Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, which had a long history with the service, was ready with a jet-powered version of its storied “cats.” (The F4F Wildcat and F6F Hellcat were the mainstays of the Navy in the Pacific during World War II, and the F8F Bearcat is generally considered the king of propeller-driven fighters, though it entered service in the Navy too late to see combat in World War II.) The Grumman F9F Panther was a conservative design; it had straight wings, a conventional tail, and the rugged structure for which Grumman had earned the nickname “Iron Works.”

But the Panther played a significant role in ushering the Navy into the jet age. It flew the vast majority of the service’s combat missions in Korea and was the first Navy jet to shoot down a MiG. The Panther never achieved the iconic MiG-killer status of the glamorous swept-wing F-86 Sabre; it earned a different reputation. While it performed the dangerous grunt work of ground attack, it became known as a tough bird that brought its pilots home, including three Korean War pilots who either were, or would become, celebrated American heroes: Boston Red Sox slugger Ted Williams and future astronauts John Glenn and Neil Armstrong. What little glamour the Panther won came Stateside: It became the first jet flown by the Blue Angels, the Navy’s flight demonstration team.

According to Corwin A. “Corky” Meyer, Grumman’s chief test pilot during the 1940s and ’50s, Grumman itself lagged behind the rest of the industry in jet fighters because of its long-term policy of “cautious prudence in approaching all new things.” One Grumman policy, for example, was to use only proven production engines for new aircraft. John Karanik, Grumman’s propulsion chief, had concluded that available American engines like the Allison J33 and Westinghouse J34 weren’t reliable enough for single-engine overwater flying. So Karanik traveled to England, where Frank Whittle in 1937 had built and tested the first turbojet engine. There, Karanik found his Panther powerplant: the Rolls-Royce Nene, a 5,000-pound-thrust, centrifugal-flow turbojet that was more powerful than anything the Americans had, and had also proven very reliable. The first two XF9Fs flew with Nenes, and Pratt & Whitney would be granted a license to produce the Nene under the designation J42 for production aircraft.

The first Panther took to the air in November 1947, from the 5,000-foot runway at Grumman’s Bethpage, Long Island plant. The weather conditions were “the foulest of any first flight in my experience,” recalls Meyer in his 2006 memoir, Corky Meyer’s Flight Journal. (He died in 2011.) For safety’s sake, the first landing had been planned for the longer runway at nearby Idlewild (now JFK) Airport. Soon after takeoff, Meyer executed a few stalls and found the Panther well behaved. He said it “performed like a J-3 Cub.”

Meyer would discover, however, that when he began testing its emergency fuel control, the new jet wasn’t so docile. At 33,000 feet the engine flamed out and, despite many attempts, would not restart. Finally, at 3,000 feet, Meyer abandoned efforts to restart and set up for a belly landing in a Long Island potato field. Miraculously, on short final, the engine restarted by itself, and Meyer managed to pull up and land safely at Bethpage.

When the Navy took over testing of the Panther, the jet suffered an embarrassing moment hardly in keeping with Grumman’s reputation. During its first arrested landing, on a runway at the Navy’s test center at Patuxent River, Maryland, the sudden jolt to the tailhook pulled off the entire tail section. The engine was still firmly attached to the forward fuselage and running normally. The pilot, believing he had simply missed the cable, applied full power for a go-around. Alerted by radio to his predicament, the pilot aborted the tailless takeoff. (Subsequently, Grumman strengthened the tail attach joint.)

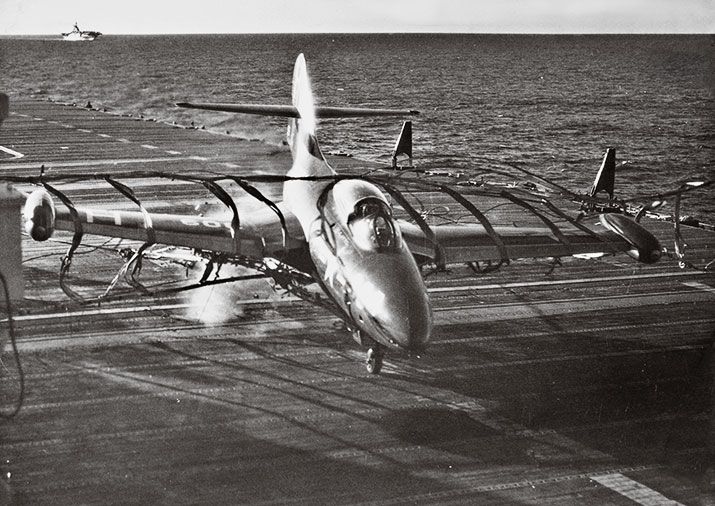

The Panther entered the fleet in 1949, and landings continued to present problems. “I flew the Panther during my first cruise on the USS Boxer,” says Robert Morris, a former Navy pilot who lives in San Diego, California. “I would end up in the barricade a number of times because of a faulty tailhook. The Panther had a bad hook dashpot [a hydraulic cylinder that dampens movement]. The hook would bounce up and down across the deck.” The Boxer, like other carriers, had a barrier that would catch an airplane in case of just such a problem with the arresting gear. On one trap, Morris put his Panther down in perfect position, but “the hook was skipping right over all the wires. On one of my barrier encounters, the canopy came off its hinges and hit me on the shoulder.”

Pilots assigned to Panther cockpits were a mix of World War II veterans, with hundreds of hours of prop time, and those who went straight from flight training to the jet. “I was in a very early F9F-2 squadron, out of [Virginia Beach’s Naval Air Station] Oceana,” says World War II veteran Dan Stinemates. “We were told we were getting rid of our Corsairs and getting new Panthers. We got our planes directly from Bethpage.”

For Stinemates, who would eventually fly the Vought F7U Cutlass, one of the most challenging—and deadly—Navy fighters ever built, the initial jet training program was minimal, to say the least. “Things have changed a lot since those days,” he says. “The ops officer said, ‘You and I are going to read the F9F manual and pick up the two planes that are ready.’ We read the manual, drove to Norfolk, and got in two F9Fs. [We] plugged in the external power, hit the ‘Go’ switch, taxied, and flew off.” Grumman’s ferry pilots weren’t even around to brief Stinemates and his squadron mate, but he was unconcerned: “It’s got a stick and a throttle. What’s the big deal?” says Stinemates today.

After takeoff, Stinemates found the Panther very pleasing to fly. He spent about 20 minutes getting to know the aircraft, stalling it and putting it through basic maneuvers. And he discovered that the hallowed advent of the jet age brought a welcome, but pedestrian, benefit. “I started out in World War II flying F4Fs,” he says. “I was flying those prop planes on the East Coast. You know what the humidity is like there, and our nylon flightsuits were just wringing wet. It was a hot summer day, and I can’t tell you how happy I was to get in the air-conditioned cockpit of that F9F.”

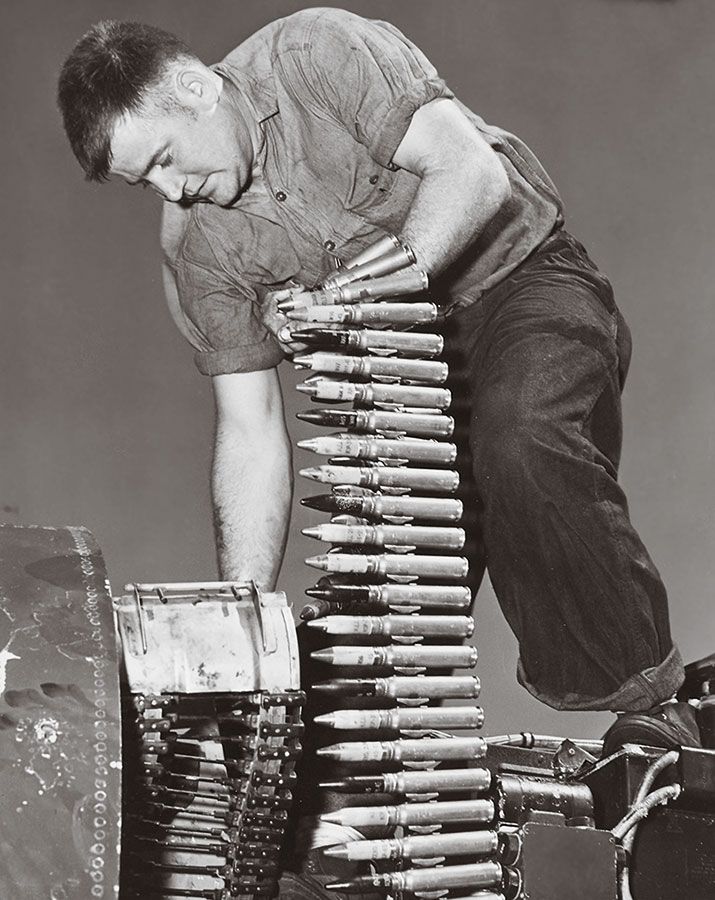

Royce Williams, who began his career in open-cockpit biplanes and worked in the plastics industry after retiring from the Navy in 1980 (although he was briefly recalled in 1981), transitioned to the Panther from the brutally powerful F8F Bearcat. “The Panther was extremely quiet, and you didn’t have the torque, [so you] went straight down the runway,” he says. “It didn’t maneuver any greater than the Bearcat—in some respects less—but there was something about flying a jet. It was more advanced. It had better radios, had TACAN [Tactical Air Navigation], and its gun systems were very reliable. Everything seemed like a step up.”

In an attempt to provide a better transition for propeller-trained pilots, the Navy eventually offered more training for its prospective jet pilots and bought Lockheed F-80s from the Air Force. “Before I flew the Panther, they sent me down to Pensacola to fly the F-80,” says Neale Smith, who found his way into Navy fighter squadron VF-22, which had the F9F. “It was very exciting. I flew the first Panther, which had 5,000 pounds of thrust and the [license-built] British Nene engine, and then we got a new version that had about 300 more pounds of thrust.”

After flying Vought Corsairs, Smith, who would go on to log time at United Airlines flying everything from the DC-3 to the Boeing 727, was unwillingly assigned to a squadron that flew TBMs, hulking World War II torpedo bombers modified for electronic countermeasures missions. “My buddy and I went to the assignments officer at Norfolk and said ‘We’re fighter pilots and we don’t fly these things,’ ” he says. Smith’s frequent, and annoying, visits finally paid off. “Two pilots had just been killed in VF-22, and that’s how we got into VF-22,” he says. “I loved the speed and the ‘flat hatting’ [high-speed passes at low altitude]. What else was a 22-year-old supposed to do?”

The Korean War began in June 1950, and almost immediately the Panther was in combat. On July 3, a VF-51 Panther stationed aboard the USS Valley Forge shot down a North Korean piston-engine Yak-9, the first air-to-air kill by a Navy jet.

On November 18, 1952, the Panther had its greatest moment of glory. Under cold, overcast skies, a flight of four F9F-5s launched from the USS Oriskany on a combat air patrol near Chongjin, which was sufficiently close to the Soviet Union that the Panthers were needed to protect Task Force 77, which consisted of 25 ships, including three carriers and the famed battleship USS Missouri. At about the time the ship’s air controllers reported unidentified aircraft inbound from the north at 55,000 feet, a fuel pump warning light in the flight leader’s aircraft blinked on. As the flight leader and his wingman returned to the ship, circling until they could enter the next landing cycle, the other two Panthers, flown by Royce Williams and his wingman, David Rowlands, climbed in pursuit of the bogies. Breaking out of the overcast at 15,000 feet, Williams spotted seven MiG-15s, abreast, streaming contrails far above.

As the Panthers were climbing through 26,000 feet, the MiGs split into two groups—four in one, three in the other—and dove on them. In the ensuing melee, Williams would be credited with four kills, and after the shootdowns would bring his Panther back to the Oriskany stitched with holes from MiG cannon fire. Rowlands, whose guns were jammed, tried to harass the MiGs, and get good gun-camera film. “He got in behind the MiG that got me,” says Williams. “He explained he wanted to show my wife what happened.”

The MiGs were flown by Soviet pilots, and Williams was quickly sworn to secrecy about the pilots’ nationality. “A [National Security Agency] group was aboard a cruiser off the coast of Vladivostok listening and watching,” says Williams. “They didn’t want to reveal the NSA group, because this was their first operation.”

How did the Panther manage to outfight the faster, higher-flying MiG? Undoubtedly, some of the credit goes to the better-trained U.S. pilots. But the Panther was a deceptively capable dogfighter. “The F9F was clearly designed as a pilot’s airplane,” says former U.S. Air Force historian Richard Hallion. “With its straight wing, it could easily turn inside the MiG-15. The pilot was superbly positioned, with great visibility. And the Panther had better guns. If he wasn’t careful, a MiG pilot in a dogfight with a Panther could be in a world of hurt.”

Williams, the Navy’s top MiG killer, wasn’t the only Williams to make it home in a badly damaged F9F. Baseball icon Ted Williams, a Marine reservist called to duty from the Red Sox in 1952, had a very close call in Korea. “I always marveled at how good a plane it was,” Williams wrote in his autobiography, My Turn at Bat: The Story of My Life. A combat rookie, he once got too low on a ground-attack mission and was hit by small arms fire. “All the red lights came on and the damn thing started to shake,” he wrote. Worried that an ejection would injure his kneecaps, Williams nursed the burning airplane 15 minutes back to a Marine base, where, trailing a 30-foot plume of fire, he bellied the aircraft onto the runway at 225 mph and slid 2,000 feet before stopping, engulfed in flames. Williams leapt from the cockpit and sprinted away unharmed. He went on to play seven more seasons with the Red Sox.

Ted Williams often flew as wingman for his squadron operations officer, a clean-cut young fellow named John Glenn. “I wouldn’t be here today if the Panther weren’t such a rugged, rugged plane,” recalls Glenn from his Columbus, Ohio office. (Now 91, the first American in orbit still regularly flies his twin-engine Beech Baron.) After one ground-attack mission, during which Glenn’s damaged Panther missed hitting a rice paddy embankment “by what seemed like inches,” Glenn flew the airplane home with a hole in the vertical tail “big enough to put my head and shoulders through.” A week later, Glenn came back with a two-foot hole in the wing.

Fellow astronaut-to-be Neil Armstrong, who died last year, also benefitted from the sturdiness of the F9F. During a bombing run launched from the USS Essex, Armstrong’s Panther struck a steel cable that had been strung across a valley to snag attacking aircraft. The 350-mph impact sheared off six feet of the right wing, but Armstrong was able to maintain control long enough to reach friendly territory, where he ejected and was rescued.

“I was fortunate in many respects [in my career]—not through any talent on my part—but I got to go all the way through training with Neil Armstrong, and then through an 11-month cruise in Korea with VF-51 with him,” said Bob Kaps, who spoke to Air & Space shortly before he died last December. “If you met him, he was just like the guy next door. After the decommissioning of VF-51 in 1995, we began having a reunion every two years. I ended up staying in the next room with him at the hotel. He had a rental car, and he chauffeured me around for two days. I’ll always cherish that memory, because I told his widow that he was one of the very few people I’ve known in my life who had no downside. All the famous men and kings throughout history had a dark side. Neil Armstrong was everyone’s friend.”

After Kaps and Armstrong returned from their missions aboard the Essex, they found Saturday Evening Post correspondent James Michener, notebook in hand, in the wardroom. Michener later based his novel The Bridges at Toko-Ri, which would be made into a movie in 1954, on his time spent aboard both the Essex and the USS Valley Forge. “In particular after important missions, we’d have a post-flight interview with him,” said Kaps. “I flew on a lot of the unique missions simply because I was the squadron commander’s wingman.”

By the time the Korean War ended, in July 1953, the Panther was on the verge of obsolescence. Despite the aircraft’s successes against the MiG-15, the Navy had decided that competing with newer MiG designs required a swept-wing jet. When the initial Panther contract was signed, in 1946, Grumman had declined the Navy’s invitation to build a swept-wing version because the company felt more research was needed. But in March 1951, five months after the MiGs appeared, Grumman started work on just such an aircraft, the F9F-6 Cougar. The Cougar joined the fleet less than two years later, but never saw combat in Korea.

With the arrival of the Cougar, the Panther began to be retired from frontline Navy service. The Marines hung on to a few until late 1957. A total of 1,385 Panthers had been built. Many Panther pilots ended up flying Cougars; for most, it was their first swept-wing experience.

During the 1980s and ’90s, at least two Panthers passed into civilian hands and flew sporadically. One, rescued from a playground and restored to flying status in 1983, was flown on the airshow circuit for 11 years by Philadelphia-based attorney Arthur Wolk, who won millions of dollars in court representing the victims of commercial aviation disasters, including the crash of a United Airlines DC-10 in Sioux City, Iowa, and a string of Boeing 737 mishaps attributed to rudder malfunction. “It was more docile than any aircraft I’ve ever flown,” says Wolk, who put 350 hours on the F9F-2. “But it was underpowered. And you really had to pay attention to the fuel. At times, you could literally watch the fuel gauge needles move.”

Wolk’s Panther was destroyed in 1996 when shortly after takeoff a fuel control failed. Wolk was able to nurse the airplane around for a landing, but due to an inoperative airspeed indicator, he landed hot and slid off the end of the runway, barely escaping with his life.

The last remaining potentially flyable Panther resides at the Cavanaugh Flight Museum in Addison, Texas. In 1995, after a two-year, 25,000-hour restoration by the museum, the F9F-2B flew to the annual fly-in at Oshkosh, Wisconsin, and won Grand Champion Warbird. But it hasn’t flown since. “It’s very expensive to fly, and it’s the last one left,” explains the museum’s Doug Jeans. “We just have no desire to fly it anymore.”

The unrefined but earnest Panther wasn’t the fastest, the highest-flying, or the most lethal postwar fighter. Yet it introduced thousands of pilots to jet aviation, primped for the Navy as a shiny Blue Angel, and even had a second career with the Argentinian navy, for which it flew until the late 1960s. It was a handsome little jet, stalwartly true to its Grumman cat lineage.

David Noland still has the complete set of the Topps “Wings” airplane cards that he collected at age seven, including card number 100, the F9F Panther.