Where Real Warbirds Go to Fly

At the Flying Heritage & Combat Armor Museum, the thrill of standing face to face with the past.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/16/73/16738bc7-4eac-41ae-87b2-cf6ef9f13570/06t_fm2018_zero0505_crop.jpg)

One day soon, before the end of this year, Steve Hinton will climb into the cockpit of one of the most significant fighters of World War II—one of the few World War II fighters he hasn’t flown—and take it up on what is likely the first flight of its type since 1946. Unlike all the other airplanes of that era that Hinton has piloted, this one’s a combat jet, the world’s first operational one, and the very Me 262 Schwalbe (Swallow) captured at Lechfield, Germany, in 1945 and later test flown at Wright Field, Ohio, by U.S. Army Air Forces Colonel Harold Watson. It will be the only authentic flying Me 262 in the world.

Original Jumo 004 engines have been undergoing restoration with improved metal parts for 14 years; the airframe, complete except for the cowlings, which will be added after the engines are installed, took 12. Warbird owners are known for long, loving, million-dollar restorations, but even in this wealthy community, an owner willing to undertake a project of this magnitude, running to the multi-millions, is as rare as the airplane itself.

Paul G. Allen, co-founder of Microsoft, began in the late 1990s to assemble the collection now known as the Flying Heritage & Combat Armor Museum (FHCAM) at Paine Field near Seattle. A philanthropist who founded the Allen Institute for Brain Science and financed the creation of SpaceShipOne, the Allen Telescope Array for extraterrestrial research, and most recently, the discovery of the wreck of the USS Indianapolis, Allen says he has felt a connection to World War II from a very young age. “My father was in the Army in World War II and landed on Omaha Beach after the first wave,” he says. “The explosion of technology and progress in aviation during [the war] was simply mind-blowing. So the idea behind the museum was really simple: I wanted to bring some of that technology back to life for people to experience but also as a tribute to our heritage as Americans and the service of people like my father who risked so much.”

To bring the technology to life, Allen has created a museum around 28 historic aircraft, restored to unprecedented levels of authenticity. FHCAM now includes eras beyond World War II, as well as tanks, artillery, and interactive exhibits. And undisclosed restoration projects are under way. More legends are coming.

Almost all of the airplanes in the Flying Heritage collection have honest-to-goodness combat histories. Its P-51 Mustang, a latecomer to the war—the airplane didn’t make it to England and the 8th Air Force until February 1945—helped make its pilot a fighter ace.

Harrison Bruce “Bud” Tordoff, a student of ornithology before enlisting in 1942, didn’t mind poking a little fun at Army bureaucracy, which by 1945 insisted on approving the names pilots gave their airplanes. For his Mustang, Tordoff chose the scientific name for a bird, the hoopoe. Upupa Epops probably confused a censor or two. On one of the 26 combat missions Tordoff flew in the airplane, he got one shot off at an Me 262, achieving his fourth victory. “As usual, I forgot to take any pictures of the plane while it was burning,” he wrote nonchalantly in his pilot report; “nevertheless I claim one Me 262 destroyed—by one .50 cal bullet.” Soon at the Flying Heritage museum, Tordoff’s Mustang will have the chance to re-enact that flight.

Discovered in a forest outside St. Petersburg in 1989, a Focke-Wulf Fw 190 A-5 had lain undisturbed since the 1943 day its German pilot managed a dead-stick landing. British warbird hunters extricated it, and FHCAM acquired it in 1999. It is one of two Fw 190s on display. The other, an Fw 190 D-13, its Jumo V-12 engine stuffed in a long nose, is the only surviving D-13. “There are some aircraft in the collection so rare that we’ve decided not to fly them,” says FHCAM executive director Adrian Hunt. That distinction belongs to the D-13 model Focke Wulf as well as to the last Nakajima Ki-43-I Oscar, a Japanese fighter. If a type is represented by displays in other museums, FHCAM will restore theirs to flying condition.

For half a century, FW 190s were in museums and history books. Today, a single original 190 flies. Seeing it fly inspires the wonder portrayed in the film Jurassic Park, when the characters first see living dinosaurs. Like all the airplanes at the Flying Heritage museum, the Focke-Wulfs are perfect. And they are real.

First generation technology, the Jumo 004 engines that powered the Me 262 in 1945 had a life expectancy of about 25 hours. When the captured jet was flown in the United States, flight trials were discontinued after eight flights required four engine changes. The Germans had just invented the jet engine and “were learning how to refine it, let alone have it work well in combat,” says Jason Muszala, FHCAM’s manager of restoration and maintenance. A team at Aero Turbine in Stockton, California, working with the original two engines and five others acquired from around the world, has almost tripled their lifespans. Says Muszala: “We have a lot of blueprints, but we basically have to operate the engine, discover the weak points, and figure out how to fix them.”

Tank killer. The Ilyushin Il-2 Sturmovik attack aircraft was a fearsome purpose-built machine equipped with 37mm cannon, rocket and grenade launchers, and cartridges carrying 192 armor-piercing bombs. It was built in greater numbers—more than 36,000—than any other military aircraft in history. But few survived the war.

In 1991, a Russian restoration shop called Flight Magic, which had restored the museum’s Japanese Zero, had located four of the dive bombers and proposed using them to create one that could fly. “Most of the aircraft is original, but parts came from four different wrecks,” says FHCAM curator Cory Graff. “No one had built a flying Sturmovik.” Now, someone has.

Many historians CALL the Messerschmitt Bf 109 the first modern fighter. It made its combat debut in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War; with retractable landing gear and all-metal construction, it left behind the open-cockpit, wood-and-fabric biplanes developed for World War I. “It was the fastest military plane in the sky for six years,” writes FHCAM curator Cory Graff in the book The Flying Heritage Collection, “until another German plane, the Focke-Wulf Fw190, supplanted it.”

If its performance against the beloved Supermarine Spitfire during the Battle of Britain was unimpressive, that may be because by the time the 109s arrived at the British coast, they had about 20 minutes to fight, before their pilots had to head home to avoid running out of fuel. The pilot of the Heritage Collection’s Bf 109 (“Bf” for Bayerische Flugzeugwerke, the firm employing Willy Messerschmitt when he designed the fighter) lost his air battle. His fighter crashed on the French coast and he was killed. Graff writes: “In 1988, a man walking on the beach near Calais noticed a piece of metal sticking out of the sand.” In 2007, the restored 109 became part of the Heritage Collection.

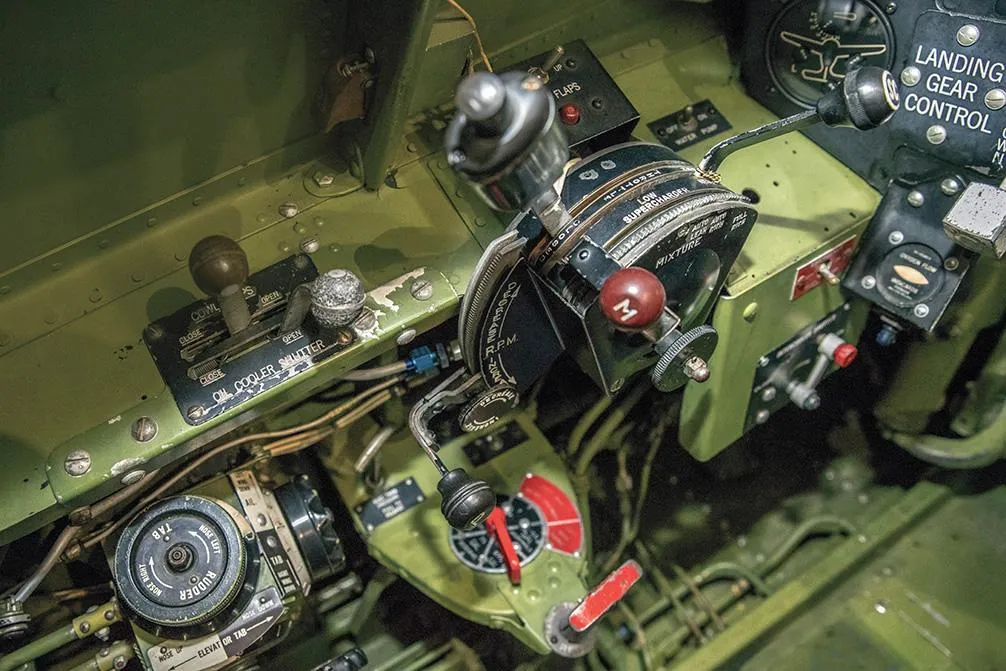

Besides overseeing restorations and maintenance at the Flying Heritage museum, Jason Muszala gets to fly several of the airplanes—the Zero, Mustang, Mosquito (as co-pilot), and the Fieseler Storch, an observation and liaison airplane the Germans used for everything except fighting. (The entire collection is on view at flyingheritage.com.) What’s it like to fly a Storch? “Slow,” says Muszala.

The faster Mustang and Zero, he says, are worlds apart but “perform extremely well in their own ways. The Mustang will out-climb and out-dive; it’s more stable at higher airspeeds.” Of the Zero, he adds: “It’s such a clean airplane [one with low drag] that getting it slow enough to extend the landing gear can be a challenge. The turning ability is just incredible. It became famous for being able to out-turn American fighters, and it’s all true.” If there were a dogfight between the two, he says, “it would probably come down to who was flying.”

The Zero and the Mustang were for the most part in two different theaters, but the Zero and the P-40 tangled often. Muszala calls “surreal” the moment when he first looked at an authentic P-40 through the gunsight of an authentic Zero.

About that P-40: “Even perfectionists sometimes make compromises,” says Adrian Hunt; the paint scheme on the Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk is one. The aircraft did see combat, but not as a mount for the American Volunteer Group—the Flying Tigers, who fought the Japanese in China. Instead, shipped to England in 1941, then to the Soviet Union, this P-40 defended Murmansk against invading Germans. “Obviously it wasn’t flying around Murmansk in Flying Tiger colors,” says Hunt, but “because of history and interest” and because it’s the very model the Flying Tigers flew, it wears shark’s teeth.

The Grumman F6F Hellcat dashed into World War II in 1943 like a big brother called on to beat up its little Wildcat brother’s tormentors. The muscular F6F was equal to the task. By war’s end, U.S. Navy, U.S. Marine, and British Hellcats had destroyed 5,203 Japanese airplanes, 19 times the number of Hellcats lost.“My two favorites [in FHCAM] are the P-47 Thunderbolt and the Grumman Hellcat, which are kind of the Army and Navy version of the same concept,” says curator Cory Graff, “the big, ugly, bouncer, bruiser type of airplane.”

It was around this particular Hellcat—an F6F-5N night fighter, which came to FHCAM in late 2000 after flying 856 hours with the Navy and a few more during its post-war ownership by various collectors and museums—that a stirring reunion occurred. Concentrations of warbirds tended by a staff tasked to get the experience of history to the largest number of people can trigger astonishing coincidences. The reunion was one of those.

One day a call came into the museum from local resident Ray Owen, who had seen video of Commander Robert Turnell, one of 340 veterans in the museum’s online World War II oral history archive, “Chronicles of Courage.” Turnell spoke of flying Hellcats with Fighting Squadron VF-81, and Owen recognized the squadron number from a composite photograph that had hung on his father’s wall for 72 years. His dad, Lieutenant Ray H. Owen, reported to that squadron in 1944. Owen and Turnell flew Hellcats together from the USS Wasp.

Museum marketing and events coordinator Michelle Donoghue arranged for the two veterans to meet at the museum. While Graff took their families on a tour of the collection, says Donoghue, “we closed the museum so they could get to know each other again.” You can see a video of the reunion at airspacemag.com/F6Fvets. Have a handkerchief handy.