On the Arizona and After

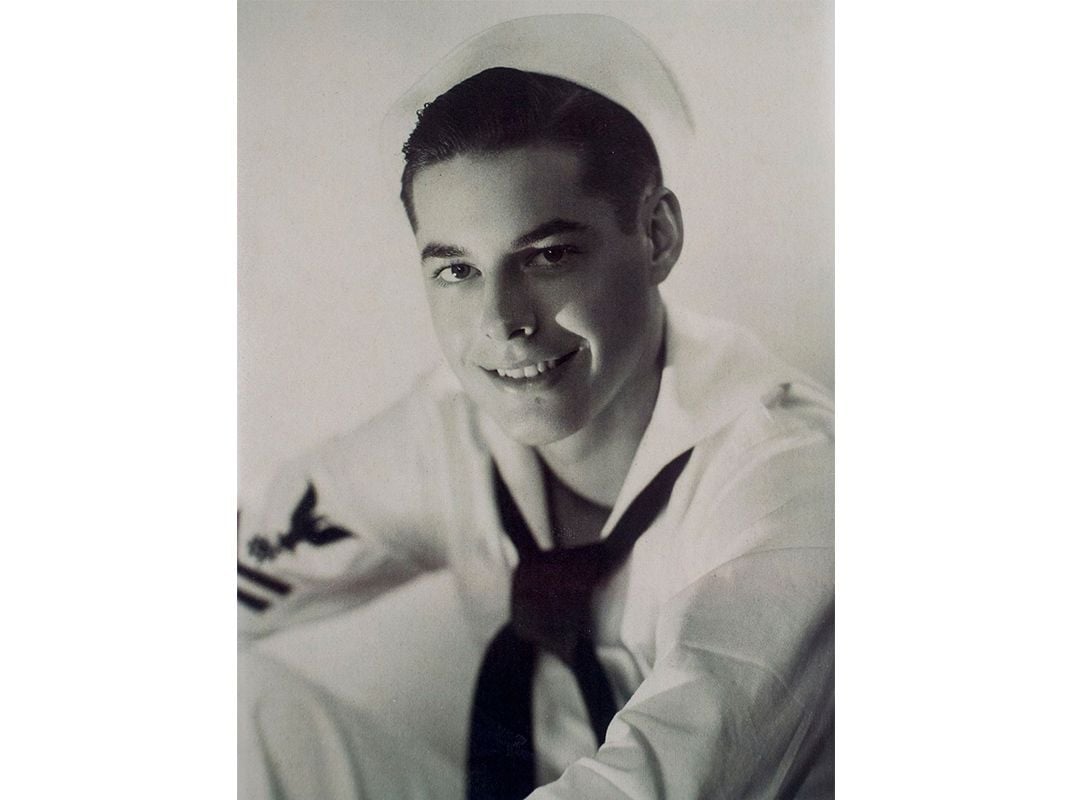

Navy Quartermaster Lou Conter survived the attack on Pearl Harbor to fly and fight another day.

:focal(505x495:506x496)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/23/a6/23a65fd4-3843-473d-96d7-674814246a5c/09e-f_dj2017_opener_live-wr1.jpg)

Lou Conter was born in Ojibwe, Wisconsin, in 1921 and grew up in Gallup, New Mexico, and Denver, Colorado. He joined the U.S. Navy in 1939 after high school, and was serving on the USS Arizona when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Of the 335 men on the ship who survived the attack, only five remain. Writer Paul Glenshaw interviewed Conter in September 2016, two days after Conter’s 95th birthday.

Glenshaw: What inspired you to enlist?

Conter: I was out of high school about four months. I was going to go to Colorado University, but a neighbor named Duley Wicks was on the [USS] Nevada as a signalman. His four years were up and he came home on 90 days’ leave. He went down to re-enlist and his brother and myself and [our friend] Ed McClure went down with him. The recruiting officer told us there was a 13-month waiting list to get into the Navy. [But] it wasn’t two weeks and they called. My mother answered the phone and said, “Are you in trouble, Louis?” It was the Navy Department. They said they were six short of their draft. So I went down and talked to them, signed up, and at 5:45 that night I was on my first train ride to San Diego. I was 18. I didn’t need anybody to sign for me. And two and half years later, Pearl Harbor hit, and I was in for life.

Where did you serve on the Arizona?

I went from boot camp right to the Arizona. My general quarters station was the lower handling room of turret two, which later blew up [in the attack]. After about six months, the chief quartermaster came down and said, “Lou, I see you’re reading a lot and not raising hell like the rest of the guys. How would you like to be a quartermaster?” I knew [quartermasters] never had to scrub decks; they worked with maps, charts, and grids. So I said sure. A week later, I was transferred into the navigation department. And that’s where I ended up in Pearl Harbor: as a quartermaster.

How did you decide to apply for flight school?

Before Pearl Harbor, there was a guy named B.J. Johnston from Texas—a fifth division gunner’s mate. He was on the football team and so was I. He said, “Lou, let’s sign up for flight school,” and I said, “Flight school? I’ve never been in a plane. And we’re right-arm rates [strictly seagoing jobs] and they’re not gonna take us.” A couple of weeks later I was over at a friend’s house for dinner, and he worked for Commander Calhoun, the commander of base force. The admiral also came for dinner. He asked me what I was doing and I said, “I’m a third-class quartermaster on the Arizona.” I told him about wanting to go to flight school and being a right-arm rate, and he said, “There’s no law against any rating going to flight school as long as you pass the exams. I write the orders.” We got them. We were going to go back [to the U.S. for flight school] on the [ocean liner] Lurline in November. Captain Van Valkenburgh called us down and said, “Johnston and Conter, we’re going back to Long Beach on the 19th of December to pick up our 1.1-inch [quadruple machine gun mounts]. So I’m not gonna waste Navy money sending you back on the Lurline. You can wait and go back with us.” So we lost our orders on December the 7th. They went down with the ship.

Please describe December 7th.

I was quartermaster of the watch on the quarterdeck [toward the stern of the ship]. The officers had their duty on the deck of the ship. The Vestal was outboard of us. We were tied up next to the quays. I went on duty at quarter to eight. It was five minutes to eight when the first [Japanese] planes came across.

They sounded general quarters immediately. We had the band on the fantail, or maybe a third of them, to play colors at eight o’clock. They laid down their instruments and all went to their battle stations. The newspapers—for years—said that the band had played in a battle of the bands the night before and they could sleep in, and they were in their bunks and they got killed. That was a big lie and it took us 50 years to get it out of the official reports. When they sounded general quarters, everyone in the band went to their battle stations.

We didn’t last long. We had Commander Fuqua. Captain Van Valkenburgh and Admiral Kidd had already gone to the bridge and told me to secure the quarterdeck and come to the bridge, because I was channel helmsman. I always steered the ship out of port. We cut the lines to the Vestal to kick her out and get under way, out of the harbor and out to sea, but nine minutes after eight, we blew up.

We took a bomb down along number two turret on the starboard side, forward. It went through five decks to the lower handling room. A million pounds of powder for turrets one and two blew up. The forward part of the ship completely blew up.

The Nevada got under way, and she got to the end of the channel. The whole Japanese air fleet dove on her to sink her in the channel, which would have closed it for months. Her chief quartermaster beached her. They were going to court-martial him, but later they gave him the Medal of Honor for it.

We were on the ship about 35 minutes. It was burning all forward and the men were coming out from the side. They were burned and they were trying to jump over the side. Commander Fuqua told us to lay them on the deck to get them into the motor launch and get them to the hospital—even if we had to render them unconscious. We got about 20 of them laid down. They were pretty bad. We got them in the motor launches and got them to the hospital. We only got about 20 of them out. Everything was such a mess—it blew so high. It was pitiful.

We still had a million pounds of powder in turrets three and four in the aft end of the ship that didn’t blow up—and that’s still there on the memorial.

How did you get off the ship?

We were tied up right alongside the quays, and there were Liberty launches tied up too. We put the men who were burned in them, so we just walked from the bridge right onto the quays on the starboard side. Some of the guys were jumping off the ship, but when they jumped—the oil [in the water] was all burning. None of them were hardly trained to swim in burning water. When you come up to take a breath, you throw the flames away from you with your hands, then you go back underwater and swim. They weren’t trained in that, so it was bad.

Lauren Bruner and Don Stratton [two of the five Arizona survivors still living] were fire control, and they were up on the foremast, which blew up. The Vestal threw a line across to them. They went across the line, got burned too, and some of them fell in the water. Lauren and Don got burned over 75 percent of their bodies. We got them to the hospital. Don was in the hospital for two and a half years, went back to the United States, got discharged. Lauren was in the hospital about eight or nine months. They said he was okay, and they put him on a destroyer. He didn’t come back until January 1946. He was in about eight or nine major battles in the Pacific—after being burned over 75 percent of his body. Lauren is really quite a guy.

What happened after the bombing?

We took the guys over to the hospital, dropped them off, went back, [and] got the fire hoses to fight the fire. We took the motor launches and helped get in underneath the fire with the hoses until Tuesday night—for 48 hours. Then Tuesday night we went over to the base and crapped out for 12 hours. It took the ship about 10 days to cool down. We dove on the ship—about 20 or 30 of us—for 10 days. We brought 18 or 20 bodies up, until they called it off. It was getting too dangerous and we weren’t going to find anyone alive. So then I was sent to Honolulu to stand patrol. No one out after sunset or before sunrise or they got shot. We held it tight. We had to—we didn’t know what we were dealing with.

How did you finally make it to flight school?

I was working base force, and Johnston was on a destroyer. I was back at my friend’s house the first week of January, and Admiral Calhoun came in for dinner. He said, “I thought I sent you to flight school,” and I told him I’d lost my orders on the Arizona. Boy, it wasn’t a week later he pulled Johnston off the destroyer and me off base force and we were on the Lurline back to San Francisco.

[On the way] to Pensacola, I went through Denver, and saw my mother and dad. [They had previously received a telegram saying that Conter was missing after the attack. He still has the telegram.] My mother said, “What are you going to do?” I said, “I’m going to be a pilot.” She said, “Oh you’re really gonna get killed now.”

**********

Conter went on to serve with Navy squadron VP-11, called the Black Cats because their PBY Catalinas were painted black for night operations. He was shot down twice, once ending up swimming with his crew while sharks circled. He participated in the rescue of over 200 Australian shore watchers up the Sepik River in New Guinea. There was minimal clearance for the Catalina’s wings, and the river was filled with logs and crocodiles. After the war, he became an intelligence officer, flew combat in Korea, and created the Navy’s first SERE program (survival, evasion, resistance, and escape).

Every year since 1991, he and other survivors of the Arizona have been sharing their experiences with high school students. Conter will return to the Arizona on December 7, 2016, for the 75th anniversary of the attack. Conter will eventually be buried on the Arizona, as have several fellow survivors, whose funerals he has attended.