Persian Cats

How Iranian air crews, cut off from U.S. technical support, used the F-14 against Iraqi attackers.

FIVE YEARS BEFORE THE 1979 Islamic Revolution transformed Iran, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, a pilot who had earned his wings in 1946 flying a British Tiger Moth, arranged for Iran to purchase 80 Grumman F-14A Tomcats and 633 Hughes AIM-54 Phoenix missiles for $2 billion. (The Iranian deal is credited with saving the F-14 program, which Congress had stopped funding, and by some with saving the Grumman Corporation from bankruptcy.) Iran became the only country besides the United States to fly the big fighter. How useful the F-14 was in the eight-year war that Iran fought against Iraq following the revolution has been a matter of controversy. Many U.S. military analysts have dismissed the significance of airpower in the conflict, but the testimony of the Iranian Tomcat pilots paints a different picture.

Information about the Iran-Iraq air war is difficult to come by. It is impossible to tabulate, for example, how many air-to-air victories were scored by Iranian F-14s because air force records were repeatedly tampered with during and after the war for political, religious, or even personal reasons. Even today, most Iranian pilots will speak about their experiences only on the condition of anonymity. Several pilots quoted here insisted on pseudonyms for their protection.

What is known is that in the 1970s Iran needed an air superiority fighter that could end incursions into its airspace by Soviets flying MiG-25Rs, and the F-14 was up to the job.

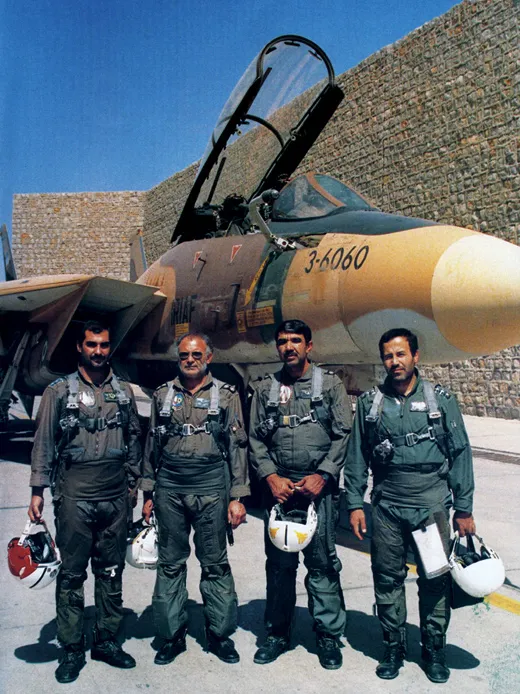

By 1979, 120 pilots and radar intercept officers in the Iranian Imperial Air Force (IIAF) had been trained in the United States and Iran, with 100 additional personnel still in training. Simultaneously, maintenance technicians were trained at Pratt & Whitney and Hughes on the engines, avionics, and weapons systems.

“We trained with many U.S. Navy pilots [who have, over the years] ‘shot down’ U.S. Air Force and Israeli F-15s and F-16s almost at will in all [training] exercises,” recalls Colonel (then-Captain) Javad. “They trained us well.”

Before the arrival of the F-14s in Iran, a giant air base was built in the central Iranian desert. Khatami Air Base, named after legendary IIAF commander-in-chief General Mohammad Khatami—killed in a paragliding accident in 1975—was to become the main hub for F-14 operations in Iran. By late 1978, 284 Phoenix missiles were also delivered, including 10 ATM-54A training missiles, and the IIAF launched a series of live-fire tests.

“The AIM-54 was truly a deadly system,” says Farhad, a former pilot. “During the testing in Iran, we tracked an AIM-54A at Mach 4.4 and 24,000 meters [15 miles] before it scored a direct hit on the target drone. This large and hefty missile had no snap-up or snap-down limits, and could maneuver at up to 17 Gs.”

Because of the chaos and violence surrounding the removal of the shah from power, 27 F-14 pilots left Iran in 1979. This number included all but two of the original cadre and 15 pilots still in training. Javad was one who stayed. He was arrested by a close friend at gunpoint, in front of his family. When the war with Iraq began, he was released.

Javad recalls that pilots were not the only ones in danger during those turbulent days. “When the Americans left, many of our technicians went with them,” he says. “Some [who stayed] were jailed, several were murdered by the new regime.”

To make matters worse, “Hughes technicians had sabotaged 16 AIM-54As at Khatami Air Base before departing for the U.S.,” says Captain Rassi. News reports at that time, he says, implied the whole fleet had been sabotaged and that all the Phoenix missiles had been rendered useless.

“In fact,” says Rassi, “all the other AIM-54s were safe in their sealed storage/transport cases, and permanently under guard, in underground bunkers at Khatami. Ironically, later we repaired all the 16 rounds damaged by Americans—[with] parts stolen from the U.S. Navy.”

Tensions between Iraq and the new Islamic government in Iran escalated. By September 1980, the two countries were engaged in minor border skirmishes.

With Iraq becoming more bellicose by the week and despite chaos in the Iranian military chain of command, what was now the Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force worked hard to return its F-14s to service. Most of the 77 surviving airframes were not operational, or at least had non-functioning radars, while their crews lacked fresh training and experience. As a result, when it came to intercepting Iraqi aircraft, F-14 units had come to rely heavily on ground control. Within a few days of the first clashes with the Iraqis, a dozen or so F-14s were back in service, flying patrols along the border.

The first kill by an F-14 was scored even before the Iran-Iraq war officially began. On September 7, 1980, an Iraqi Mil Mi-25 Hind helicopter (an export version of the Soviet Mi-24 attack helicopter) was shot down with a 20-mm Vulcan cannon. Just six days later, the first AIM-54 kill followed: Major Mohammad-Rez Attaie shot down an Iraqi MiG-21 while he was patrolling an area over which Iraqi reconnaissance aircraft had been especially active in previous days.

The most intense periods of air combat were the first two months of the war, which began September 22. Captain Javad, who was involved in the early actions against the Iraqi air force recalled, “There was little on the ground to stop the massed Iraqi Army from rolling east...[however,] our air force intercepted Iraqi fighters over the border, bombed the Iraqis on the ground, and launched air strikes deep into enemy airspace.”

Their F-14s equipped with the AWG-9 pulse Doppler radar, the Iranian pilots could hit an enemy aircraft from 100 miles away, but the pilots also appreciated the airplane’s fighting abilities close in. Major Farhad recalls the airplane’s maneuverability: “The capability of the F-14A to snap around during the dogfight was unequalled.... After only 100 hours of training, I learned to pitch the nose of my Tomcat up at a 75-degree [angle of attack] in just over a second, turn around, and acquire the opponent either with Sidewinders or the gun.”

Despite some 1,000 air-to-air engagements between 1980 and 1988, air battles were not a deciding factor in the war. According to retired U.S. Air Force Colonel Ronald Bergquist, a former Middle East specialist, rather than sacrifice their fighter aircraft in combat, both air forces used their fighters as deterrents, in much the same way that the superpowers at the time used their nuclear arsenals. Neither side “could depend upon having a secure enough source to ensure a continuing balance between losses and replacements,” Bergquist writes in his 1988 monograph, The Role of Airpower in the Iran-Iraq War. Unlike Israel and Egypt in 1973, he says, Iran and Iraq in 1980 had no allies and, unable to replace their losses, had to conserve their fighters. “If they’re pressed to the wall, they’ll use what they have to,” he says. “But if they aren’t, they’ll just hold them back.”

The Iran air force concentrated on its ability to act as a deterrent, and used its F-14 Tomcats to defend strategically important installations, primarily Iran’s main oil-exporting terminal at Khark Island.

“During the first few weeks [of the war, the Iranians] did a good job of deterring Iraqi air power and actually forcing Iraqis to at least consider the fact that Iran could attack,” says Anthony Cordesman, the Arleigh Burke Chair in Strategy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C. “But that faded relatively quickly.”

Iran at first attempted to keep some 60 Tomcats in operational condition, but intensive flying and lack of qualified maintenance personnel—not the lack of spare parts, as is commonly believed—forced it to scale back the number of operational F-14s to 40 by 1984, and to 25 by 1986.

On the other hand, the AIM-54 Phoenix missile was deployed only sporadically at the beginning of the war, and then more frequently in 1981 and 1982 until the lack of thermal batteries suspended the use of Phoenix missiles in 1986.

“Deployment of the AIM-54 requires a good cooperation between pilot and radar intercept officer,” says Hashemi. “Some pilots have had a problem to accept this fact, and there were many discussions, mainly because we have had great pilots but very few good RIOs.”

During the war, Hashemi fired four AIM-54s against the Iraqis. His first missile, shot in July 1982, was directed at a group of Iraqi MiG-23 Floggers attempting to intercept a lone Iranian F-4E that was returning from Baghdad to Iran. “As luck would have it, on this day the closing speed of the Iraqi MiG-23s brought them within the ‘kill box’ of the Phoenix I fired,” says Hashemi. “When the missile hit the lead MiG, it disappeared from my radar along with his wingman.... The MiG-23 was not the fighter the Iraqis had hoped for. It could not outmaneuver any of our fighters and we have had very little respect for them on a one-to-one basis. We were concerned only when facing large numbers of Iraqi MiG-23s, later during the war. The most impressive thing about the MiG-23 was its ability to rapidly accelerate when we chased them—but it could not outrun an F-14.”

Some of the most spectacular air battles of the war—many of them between Iranian F-14s and French-built Iraqi Dassault Mirage F1EQ fighters—involved Iraqi attempts to cut off Iranian oil exports and the Iranian defense of the oil refining and exporting infrastructure.

The Iranians suffered heavy losses in the first few months of the war, forcing them to slow their flight operations to conserve their remaining assets. Under those circumstances, even successful air-to-air engagements had only temporary significance. When F-14s were sent up to do battle against the Iraqis, the deployment usually deterred the Iraqis from flying into that area for several weeks. One or two Iranian Tomcats could force a formation of Iraqi fighters to abort their mission or jettison their ordnance before reaching the target.

“I heard many times during [and after] the war how the air force...had let Iran down or how we should have done [things] differently,” says Captain Hashemi. “Our F-14As were used only as...interceptors as they were experts for that job.” On average, about 40 percent of the F-14 fleet was combat-ready at any one time. “We knew without a doubt that this...F-14A fighter force would not give Iran total air superiority over Iraq,” says Hashemi. He says the strategy was to use the prized F-14s sparingly to keep them safe from Iraqi surface-to-air missiles but to have them ready for any strike force that invaded Iranian airspace.

Recalling his interrogation of an Iraqi Mirage F1EQ officer shot down by Iranian Tomcats in February 1986, Major Kazem, a former Iran F-4 pilot says: “Without hesitation, this man told me that he ‘knows the IRIAF was left with only some 20 [Northrop] F-5s and a dozen or so F-4s, and no operational F-14s and that all our remaining fighters were poorly flown.’ I had to keep myself from explaining [to] him the hard fact that his flight had just been shot to hell by a ‘poorly flown’ and ‘non-existing’ IRIAF F-14A.”

Thinking back on his experiences during the war, Javad has been bemused at what has been reported about the Iranian Tomcat pilots. “In the 1990s, a number of observers declared the F-14 and AIM-54 to be an ‘expensive failure,’ ” he says. “We proved the contrary to be the case. We not only shot down many Iraqi fighters, but we forced hundreds of Iraqi formations to abort their missions before reaching the target.”

Iraqi pilots seemed to have learned respect for the F-14. They faced the aircraft again during Operation Desert Storm, begun only three years after the United Nations-mandated cease fire ended the Iran-Iraq hostilities. U.S. F-14 pilots who flew the fighter on escort and photo reconnaissance missions in Iraq reported that Iraqi aircraft would break off an approach once the Tomcat’s AWG-9 radar fired up.

Today, there are still an unverifiable number of Tomcats, overhauled and upgraded with indigenously developed systems, in the Iranian air force.