*Pilot Not Included

Military aviation prepares for the inevitable

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Pilot-not-included-3-FLASH.jpg)

There comes that moment for each new U.S. naval aviator, after six weeks in the classroom, then six months in a T-34 or T-6 trainer, and a year in a T-45, when he must fly out to the ship for the first time, ignore the moths in his stomach, slam the airplane onto the deck, and hook the cable. The rookies make these trips to the carrier in groups, but each lands alone. Some will have to go around. A few will wash out altogether.

Now a new aviator is headed to Navy carriers, one that never needs training, never tires, and never gets nervous. Called the X-47B, the vehicle flew for the first time this year, in the California desert, in preparation for its first autonomous landing on a carrier, scheduled for 2013. The X-47B is a robot, and though it’s just a demonstrator, it will provide a compelling glimpse into the future of naval aviation.

Unmanned air vehicles, or UAVs, are now the fastest growing fleet of military aircraft. The 300 UAVs flying today are expected to almost triple by the end of the decade. UAVs initially proved themselves in long reconnaissance flights, but military services soon equipped some with missiles. The X-47B takes the next step: It’s an unmanned combat air vehicle, or UCAV—a UAV designed for attack. Maker Northrop Grumman and the Navy call it a UCAS, or unmanned combat air system, with the vehicle as the system’s most visible part. Whatever the acronym, the $636 million carrier landing demonstration program aims to show that these new, stealthy, increasingly self-sufficient vehicles can fly in and out of the controlled chaos of a carrier deck and perform other frontline jobs long handled by humans.

UCAVs mark not just a technological shift but also a cultural one, with computers coolly assuming missions from fighter pilots who as a group have evolved an elite-club identity, complete with its own language. When the UCAVs fly, no one will banter on the radio about “goo” (bad weather), “drift factor” (straying off course), or “pucker factor” (self-explanatory). Nobody will bother to “call the ball” (follow the glide slope light to land). The robot will merely get a digital go-ahead, then drop to the deck.

In response, pilots are expressing everything from curiosity to skepticism. Many admire the endurance, versatility, and affordability of UAVs. Others scoff that they will never replace human initiative.

“It’s probably what every group of people who ever had their job automated went through,” says Missy Cummings, a Navy fighter pilot who became an MIT professor and studies how humans and UAVs work together. “The pilot has that image as sort of the last bastion of derring-do, and perceives [piloting] skills as irreplaceable. We have an emotional attachment to the idea of being a pilot that is very hard to lose.”

The Army and Air Force adopted UAVs rapidly in the last decade for around-the-clock surveillance and occasional strikes. The Navy was slower, but is now “all in,” says Rear Admiral William Shannon, the service’s program executive officer for unmanned aviation and strike weapons. A helicopter pilot, he says UAVs will expand the Navy’s reach at far less cost than piloted aircraft.

The X-47B’s distinction may emerge in carrier ready rooms, where pilots watch one another’s landings on closed-circuit screens. Every landing gets a grade, posted on the wall. A perfect score is rare; pilots are lucky to get a few in their careers. A poor grade is an embarrassment, a sign of safety breaches that could turn fatal. “We’re very critical of ourselves and each other, but it’s a good rivalry,” says Captain Mark “Mutha” Hubbard, commander of the Pacific Fleet Strike Fighter Wing, based at Naval Air Station Lemoore in California. “Professionalism demands scrutiny, so we scrutinize each other’s passes to a high degree.”

Pilots can use the Automatic Carrier Landing System, which automates the approach and landing on a pitching deck. But that earns no grade. “It’s very competitive. I think that’s what keeps us wanting to do it in the hands-on, because we’re graded and we’re ranked,” says Hubbard.

The X-47B’s grades won’t make the ready room wall, and it won’t care. It will land flawlessly every time. Its odd geometry and nose-up angle would make it hard for an onboard pilot to see the deck anyway.

Former Navy pilot Steve “Scaggs” Bos recalls that flying fighters off carriers was “the most fun you could have with your clothes on.” He logged more than 4,000 hours in A-7s and F/A-18s, and made some 700 carrier landings. Now he works at Northrop Grumman on the X-47B. “At first, the thought that a machine could do it as good or better than you all the time was a little bit alien,” says Bos, who handles the logistics of managing the UCAV on the carrier deck. He knows that pilots will probably hold the rookie robot to a higher standard than they do one another. “It will be hard to accept it into the club until that robot does something phenomenal for you,” he says. “Maybe it gives you critical targeting information. Or meets you on a bingo profile [almost out of fuel] and gives you 500 pounds of fuel,” where a pilot might otherwise have to ditch in the ocean when his tanks run dry. “Until we go out there and prove it,” he adds, “Northrop Grumman will be perceived as just blowing smoke.”

The X-47B is a bit smaller than an F/A-18, with a bay that can hold intelligence sensors, guided weapons, or tanks to refuel other airplanes. Though manned fighters look sleek, they produce more drag than the X-47B’s flying-wing design, which offers more than 2,000 miles in range, almost twice that of an F/A-18.

“As a young man, I would have said, ‘Gosh, they’re trying to take my job,’ ” says Hubbard, who has flown more than 26 years as a Navy pilot. As a commander of more than 500 pilots, he now takes a longer view. “The unique thing in the future is I won’t have to put my blood and treasure forward to do the nation’s business. I think that is a brilliant concept in itself. But there will always need to be men in the loop to make those decisions that are critical.”

He imagines UAVs as force-multiplying wingmen. “They’re more agile, they’re more survivable, they have smaller signatures,” he says. “I can send them out there and distribute them as part of my total strike package. I have one man with potentially three, four, [even] eight UAVs on my wing. I know it’s kind of outlandish to think about, but I think that is potentially the future.”

Plenty of minds agree. Britain’s BAE Systems is developing an unmanned stealth aircraft, Taranis, with intercontinental range. Boeing’s Phantom Works is funding development of a UCAV called the Phantom Ray. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency is looking for an unmanned version of the A-10 “Warthog.”

Pilots know that the kinds of advances that brought head-up displays, radar improvements, and precision weapons will extend to UAVs, making carriers “much more lethal and powerful,” says Captain Sterling Gilliam, an EA-6B Prowler pilot who commanded a Navy air wing in Afghanistan and Iraq. Like Hubbard, Gilliam thinks UCAVs and piloted aircraft will creatively coexist. “I don’t believe the last naval aviator has been born,” he says. “But if he has, I just hope he’s not in grade school yet.”

“When the human is a detriment to the mission, then it’s time to look at unmanned,” says Craig Brown, a former Air Force F-16 flight instructor who now manages the Phantom Ray program for Boeing. Piloted airplanes carry heavy ejection seats, oxygen, and other support equipment, requiring either more fuel or less airtime due to weight. Removing people and their baggage frees capacity for more sensors, weapons, and fuel, and longer flight times than humans could stand. Brown asks: “How many humans can stay in the air for 24 hours over the same piece of geography and stay awake, let alone remain effective?”

Retired Air Force Lieutenant General David Deptula, a former F-15 pilot, was a powerful proponent of flying aircraft remotely. Today, he questions what he calls “excessive exuberance” for unmanning all sorts of aircraft. He points out that UAVs (or the Air Force’s preferred RPVs, for “remotely piloted vehicles”—the service avoids the term “unmanned”) often require more manpower than conventional aircraft because the video and other data streaming in from their ever-expanding array of sensors must be analyzed. Just because an airplane can operate remotely, Deptula says, doesn’t mean it should. “The essence of conflict warfare is a very human activity,” he says. “If it was a science, we could turn it over to machine-to-machine, and whoever had the best algorithms would win.” He recalls fighting computer simulators that were plenty tough. But, he says: “I won.”

General Ronald Fogleman was the Air Force chief of staff in the mid-1990s when he created the first air wing dedicated to UAVs. The light bulb went on for him about the importance of UAVs as he saw support building right up through the ranks to Congress. He wanted the Air Force to lead on UAVs and wanted trained pilots to fly them. “Early on, this thing was such a novelty, I really don’t think rated pilots saw it as much of a threat,” he says.

But commanders began assigning jet pilots to sit at consoles in Nevada and fly Predators and Reapers in Afghanistan via satellite, which rattled many in the pilot culture. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates complained in 2008 that getting the Air Force to field more UAVs more quickly was like “pulling teeth.” Later that year, Chief of Staff Norton Schwartz warned that Air Force culture must not treat UAV pilots as a “leper colony.” Many feel the Air Force stumbled by pushing pilots into a field they never signed up for. Today, however, says Fogleman, it is viewed as a new career field that will over time develop its own unique culture.

In the Navy, UAVs had no natural champions to pull them along, says former pilot and rear admiral Tim Beard, who commanded the carrier John F. Kennedy. Now at Northrop Grumman, he has looked at ways to integrate UCAVs into the carrier environment. He knows pilots prefer airplanes they can climb into. He didn’t see the UAV revolution coming. “Officers on active duty are primarily engaged with day-to-day operations,” he says. “There is seldom the time or the wherewithal to be looking well into the future.” Now that he’s on the contractor side, he’s a big fan of UCAVs. “We have a huge training overhead [with pilots] that we just don’t have with a UAV. Over 90 percent of aviation flying is training. The beauty of an unmanned asset is that once the software is set, it doesn’t have to be retrained.”

“I spend a lot of time explaining to pilots that we’re not trying to get rid of their job—it’s just changing,” says Missy Cummings, the former Navy pilot who runs the Humans and Automation Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Her lab tries to help people and automation benefit from each other’s strengths and account for each other’s weaknesses. One of her grad students built an iPhone application to fly little robo-copters, and in three minutes taught people off the street how to use it. She says it could just as easily operate multi-million-dollar UAVs.

The lesson: Controlling an airplane just isn’t that hard anymore. Even airliners are increasingly hands-off. Cummings’ main point to pilots is that today, “you’re needed more importantly for your reasoning, for your knowledge—not for your monkey skills.”

Cummings speaks out often and loudly: As one of the Navy’s first female fighter pilots, she flew A-4s and F/A-18s and was carrier qualified, and later wrote a book about the male hostility she faced. Today she chides the “white-scarf” mentality in which fighter pilots reign supreme. As traditional pilot skills lose currency, she says, “the fighter pilot mafia is losing its control.”

As an example of when a pilot is needed on board, she points to the day in January 2009 when Chesley Sullenberger, a former Air Force fighter pilot, used his judgment to select the Hudson River to land his US Airways A320 after geese crippled his engines.

But Cummings’ research suggests that experienced pilots do not make the best UAV pilots. Dependent on cues from the buffeting of the wind, the telltale whine of the engine, or the shimmy of the airframe, they lose those cues when they go from the cockpit to a computer console, and crash more often than those with no piloting experience, she says.

This year, an Air Force squadron dedicated to training operators of remotely piloted aircraft enrolled its first class of officers directly from their commissioning, who “have no past experience to muddy the waters, no bad habits to break” according to their director of operations (the Air Force withholds their names for security reasons). They get their own wings too: The Air Force in 2009 designed pins for fliers of RPVs, and a different style for sensor operators.

Unmanned flying resembles the moon race, with technology and commercial uses advancing rapidly, says Mike Nelson, who was an F-16 and MQ-1 Predator instructor pilot in the Air National Guard. He’s now a guest lecturer in courses about unmanned systems at the University of North Dakota’s Odegard School of Aerospace Sciences. Unmanned aviation represents the aerospace school’s fastest growing major. As for actually flying UAVs, which only the military teaches at qualified bases, it requires plenty of airmanship, Nelson says. The difference is, “your eyes have to tell you what the seat of your pants doesn’t.”

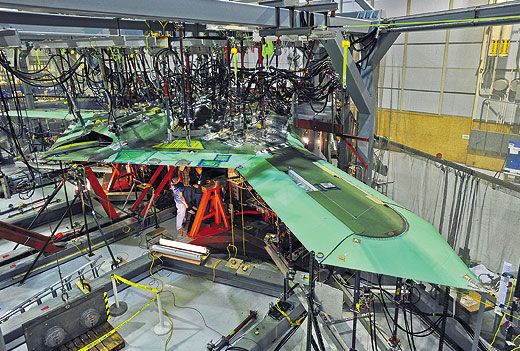

If UCAVs are going to prove themselves anywhere, a carrier deck will be the ultimate test. The Navy has a set of strict rules for safely rocketing multi-million-dollar jets off a floating airfield and landing them a minute apart. Nobody wants to mess with that. “We’re not coming into the environment to change it, but rather to fit into it seamlessly,” says Philip Saunders, Northrop Grumman’s chief engineer for the X-47B program. Like other carrier aircraft, the X-47B’s operational descendant will fold its wings to squeeze into the space. Secure data links will tie its computer to the ship’s primary air traffic control center, high above the deck.

A new navigation system will far outdo the Automatic Carrier Landing System of today, in which the piloted airplane constantly follows the rocking and bobbing of the ship. The X-47B will instead use Global Positioning System data to anticipate the ship’s movement and refine the flight path 20 times a second, about 40 times faster than a human can. Engineers say the new technology should put the airplane down an average of two feet from the centerline every time.

After it has landed on the noisy flight deck, the X-47B will need two pairs of helping hands. One will belong to a “yellow-shirt,” the standard flight deck crewman who directs pilots of manned aircraft. The yellow-shirt will face the UCAV and perform standard hand signals, while a second crewman will stand behind the yellow-shirt with a remote, watch his commands, then taxi the UCAV with the remote. That remote will be fixed to the crewman’s arm for hands-free efficiency.

Going a step further, Cummings’ MIT team hopes to do away with the remote. The team is developing an advanced technology similar to that used in Microsoft’s Kinect for the Xbox 360 video game. A sensor aboard the UCAV would theoretically see and follow yellow-shirts’ arm movements without anyone wearing a remote. Taxiing across busy decks, the aircraft would track the right person and duplicate the human faith that yellow-shirts and pilots now place in one another, says Yale Song, a graduate student in computer science in Cummings’ lab. “This is about what it means for a robot to communicate with people in a more natural way,” he says. “How do you build that trust that communication depends on?”

Admiral Gary Roughead, the chief of naval operations, wants to see humans and UCAVs working operationally together by 2018. Undersecretary of the Navy Robert Work, a former Marine commander, even co-authored a report a few years ago suggesting that the Navy’s next aircraft carrier could carry UAVs only.

A typical mission scenario doesn’t exist yet. But an operational version of the X-47B would likely take on long-distance, long-duration, long-odds missions that would be difficult or dangerous for pilots. While the UCAV is a demonstrator with no working weapons, military planners foresee its descendants providing 24/7 surveillance and limited attacks in contested airspace, or leading manned aircraft into battle zones. Phantom Ray program manager Craig Brown says that as a pilot, he would instruct loyal UCAVs to stay “out in front of me and launch missiles for me to see if I can get opposing forces to show their hand.”

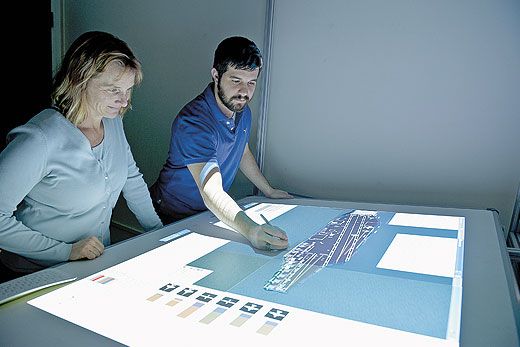

The Navy and Air Force are funding Cummings’ lab to help smooth the transition from piloted aircraft to robots. Her team is also designing a digital overhaul of the low-tech “ouija board,” a tabletop model of the flight deck that crews fill with tiny airplanes to track deck operations. Computers could take over some of these logistics to improve overall efficiency and safety. Humans and automation “build a better schedule together than either one would on their own,” says Jason Ryan, a graduate student researcher developing the deck management system. But he adds that it all depends on the quality of the decisions made by the human operator, the algorithm, and the interaction between the two.

Every fighter pilot gets a call sign, usually from a play on his or her name or by doing something really stupid. If the UCAV gets a call sign, chances are it won’t be for the latter.

Michael Milstein is a freelance writer in Portland, Oregon.