Robert Taylor’s Annual People and Planes Reunion

Stop for a spell in the Golden Age.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/87/9f/879f8d2e-fcf8-44a3-9834-efa601e1b04e/05t_jj2016_bucolicopenergoldenage_live.jpg)

Even as grass strips go, this one is spartan: It’s 2,350 feet long, and the markings are minimal. The body of an old Ercoupe, painted blaze orange, rests on a swivel to serve as the wind indicator. “It’s a challenging runway for the first time to land on,” admits Rob Bach, who for many years arrived in a 1928 Travel Air. “But it has a wonderful feeling. From the north you come over trees and a gully. It creates a bit of an optical illusion as the hill comes up.”

Since 1971 this rural Blakesburg, Iowa, grass strip has been the home of the Antique Airplane Association and its annual Labor Day weekend fly-in. Last year nearly 400 aircraft—most built in the 1930s and 1940s—assembled here, on 177 acres of rolling pasture with corrugated-metal buildings that look like they were left over from the Great Depression.

“There’s no control tower and no control zone,” says pilot Ann Pellegreno. “It’s just a very free atmosphere for aviation.” Pellegreno and her husband Don, also a pilot, fly up every summer from their home in Rhome, Texas, in their 1947 Fairchild XNQ-1, one of only three built and the last remaining in the world. “You can sit in front of the hangars and watch the airplanes come in and critique the landings,” she laughs. Landings from the north often entail a bounce or two, which the peanut gallery finds hilarious.

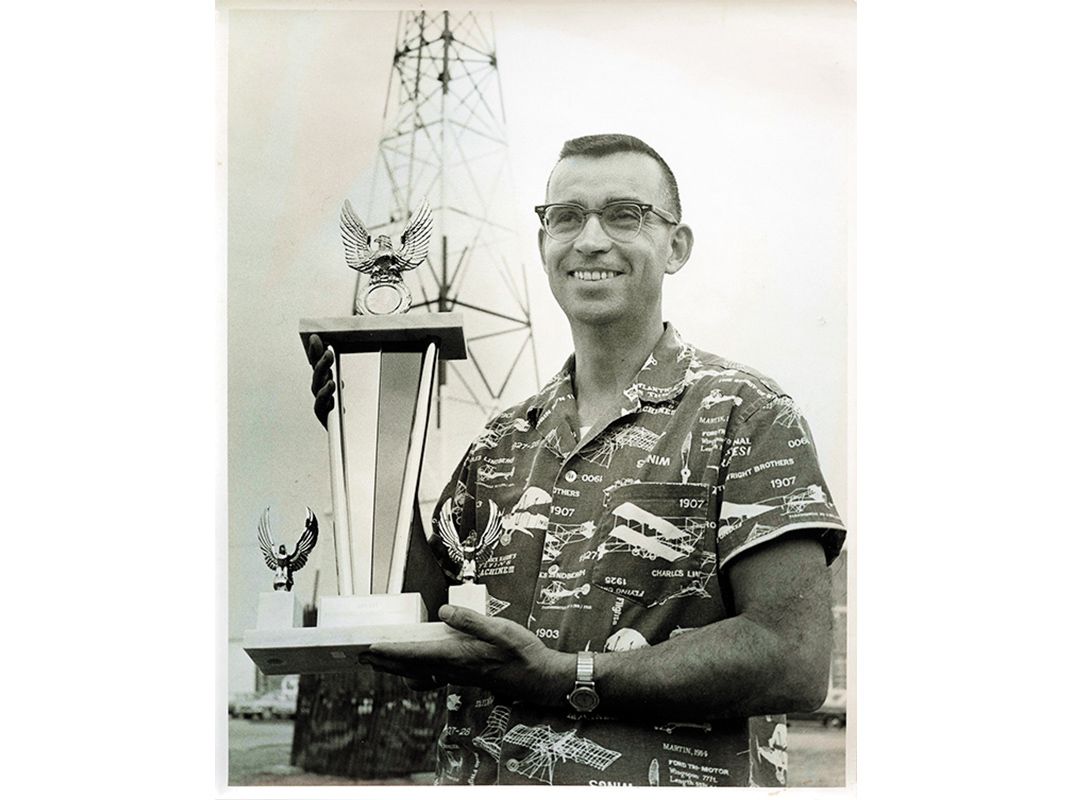

The Antique Airplane Association was created in 1953 when founder Robert Taylor decided that people who restore and fly vintage airplanes would benefit from a community. He placed a $12 classified ad in the August issue of Flying magazine soliciting $1-a-year memberships. “We got 12 members that first month,” recalls Taylor, now 91. “We broke even.” Taylor’s office is on the second floor of one of the buildings overlooking the runway; it’s a crow’s nest, dusty and jammed with books, magazines, and memorabilia. “I save everything,” Taylor says.

He rarely needs to consult the paper he’s saved because he also apparently remembers everything to do with antique aircraft: foibles, facts, people, parts, stories. “If you’re interested in restoring old airplanes, he’s your go-to guy,” says Pellegreno, who with her husband has restored 14 airplanes. “He’s very generous with his time helping people get the information they need.”

When Rob Bach acquired a rare 1961 Bentzen Sport homebuilt a few years ago, one of his first calls was to Taylor. Not only did Taylor recall the aircraft from a 1963 fly-in, he remembered someone who was there and had seen it, and he put Bach in touch with him. “His encyclopedic memory for airplanes, people, and what airplanes and projects are where is incredible,” says Bach. “He’s very passionate about old airplanes and keeping them alive.”

Taylor started the AAA after attending an early meeting of the Experimental Aircraft Association in Milwaukee, which was founded the same year. “Their whole thrust back then was homebuilts and I thought, What the hell, there ought to also be something for old airplanes,” he says. The two organizations have gone down very different paths. Today the EAA holds the largest civil airshow in the world, in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, and has 192,000 members; the AAA has 6,000. And if not for a brief childhood friendship in Taylor’s life, the Antique Airplane Association might not be here at all.

Taylor grew up around Ottumwa, Iowa, and as a boy spent time around the Ottumwa airport, about a mile from his grandparents’ farm. It was there that he sat in his first airplane, a Curtiss Robin, and in 1936 took his first airplane ride, in a Ford Tri-motor, which cost $1. He had to borrow 50 cents.

His family moved to Englewood, Colorado, during his high school years, and there he met Jack Lowe. The two boys struck up a friendship centered on their interest in aviation. Lowe had cerebral palsy and used a wheelchair. Taylor later reflected, “You know, there are people who can’t stand being around disabled people. Those people who are disabled can tell that. I never felt that about anybody. I never knew what struck him about me.” But Jack Lowe would never forget Bobby Taylor.

Taylor left Englewood before graduating, hitchhiked to California with $12 in his pocket, and found work icing donuts. On his 18th birthday, he was hired by Lockheed and worked on the center section of P-38s. During World War II he enlisted in the Army Air Forces and was assigned as a mechanic and crew chief in the Sixth Air Force. After the war, he attended the Aeronautical University in Chicago and worked at several California aerospace companies before Iowa called him home. The Army also called: He re-enlisted for a year of service during the Korean War. When he returned to Iowa, he worked for the Ottumwa Airport Commission, and later ran the Ottumwa airport’s FBO (fixed base operation). Along the way, he restored vintage airplanes for himself and other owners.

“I haven’t done anything but aviation since my 18th birthday,” Taylor says.

His fledgling Antique Airplane Association grew. In 1954 it had its first fly-in: five airplanes showed up at the Ottumwa airport. Despite the group’s progress, revenues barely covered the printing and postage for the member newsletter. To take the AAA to the next level and stabilize its finances, Taylor needed several thousand dollars, but money was tight and he had a young family. Then one night the phone rang. It was Lowe’s nurse.

“Do you remember Jack Lowe?”

“Sure I do. How is Jack?”

“Well, we got something about your Antique Airplane Association and we’d like to come visit you.”

Taylor learned that his old friend had inherited the Dayton, Ohio Lowe Brothers paint fortune (the company was later bought out by Sherwin Williams) and was eager to help the association with a check for $3,000. By 1961 the AAA had grown to 700 members, and by the early 1960s the fly-in was a major aviation happening, with over 1,000 aircraft showing up every year. When Jack Lowe died in 1968, he left $100,000 to build what became the Airpower Museum and left Taylor his Lockheed Vega, which Taylor had been restoring at the time, and all the stock in his real estate development company, worth more than $1 million. Taylor used some of the money to buy the site of the current fly-in because, in Taylor’s view, the local government was making it difficult to base the AAA and hold the fly-in at the Ottumwa airport.

The move from pavement to unmarked rolling pasture was not without its detractors, and Taylor admits the association lost a few members and encountered logistical difficulties.

Since the move, the AAA has made improvements: The Airpower Museum, now the joint sponsor of the annual fly-in, exhibits 38 aircraft. Some of them, like the 1936 Rose Parrakeet or the 1939 Brewster B-1 Fleet, have long histories with the association but are exceedingly rare. Among the museum’s prized collection is a 3,400-square-foot Library of Flight, with more than 6,000 volumes.

The association also added the primitive-looking hangars and a saloon in the small causeway between them. During the fly-in, part of one hangar becomes a “fly market,” where members can rummage through and occasionally buy old airplane parts. The market is run by Harman Dickerson, 79. Every summer he loads up his van with parts to add to the market’s mix, then drives from Columbia, Missouri, where he operates an aircraft restoration business, to Blakesburg. “There’s really no inventory taken,” says. “People bring stuff in on consignment or donate it. There has been a lot of stuff that has been donated through the years and if it doesn’t sell, it just stays over until the next year. Some of this stuff you’ll just say happy birthday to forever.”

Dickerson went to his first AAA fly-in in 1965 and still flies his own Piper P-11. “It’s like the old planes were born into me,” he says. He’s drawn to Blakesburg because “it’s more rural, with the grass strip.” He adds: “I think I live back in that time. You do feel that way when you are there. I always enjoy Robert’s company. We tell tales. We love the old airplanes. It doesn’t matter what you fly, something from World War I or an Ercoupe, he treats everyone the same. I’ve always liked him for that.”

Taylor still lives on his own, drives, and comes to the office most afternoons. He flew into his late 80s but finally quit, he says, when “my eyes got too bad.”

“I’ve always recognized that I was no Jimmy Doolittle,” he says. “Flying is one of those things that you eventually need to give up. I’m not one of these guys who is going to keep flying until he can’t talk or walk.”

The task of keeping everything moving in harmony and on a tight budget today falls to Taylor’s son Brent, 59, a pilot and airplane-and-powerplant mechanic with an inspection authorization, who runs the organization. (Taylor’s other son, Barry, also an A&P mechanic, works with the AAA on restoration projects.) Brent likens the popularity of the AAA fly-in to a Jimmy Buffett concert: “He’s selling a feeling, a dream,” Brent says. “Everyone’s got their own little version of it when they are there. Well, if you walk down the flightline here, you will get 10 different answers as to why people come.”

One theme runs through the conversations of those assembled this past Labor Day weekend. Comparing the gathering to the EAA’s annual AirVenture mega-airshow, pilot Doug Rozendaal says: “This is the antithesis of Oshkosh in every way.” Rozendaal arrived in a replica of Benny Howard’s air racer Mr. Mulligan with the aircraft’s builder, Jim Younkin. “Clearly there is a need and a purpose for both,” he continues. “Both are fun and interesting, but this is as grassroots as it gets: landing on a piece of rolling pasture, no rubber chicken dinners, and no sport coats.” (Hawaiian shirts are the preferred attire.)

Younkin, 85, a legend in both homebuilding and vintage airplane circles, just likes the relaxed pace of “being able to sit under someone’s wing and talk to people.”

Bach recalls coming to his first AAA fly-in in 1963 with his pilot parents (his father, Richard Bach, is the author of Jonathan Livingston Seagull) when he was two years old, and playing with model airplanes under Robert Taylor’s desk. “I grew up on that airport,” he says. “There are so many memories. It takes me two hours to walk 100 yards because I know everybody. You can be sitting under a wing talking to a stranger and pretty soon you realize that you are talking to a guy who used to work for Don Luscombe. Every other person there is somebody with an amazing story.”

John Ricciotti of Barrington, New Hampshire, owns the last Waco S3HD—distinguished by its canopy—in the United States. He bought it three years ago and has brought it to every fly-in at Blakesburg since, flying it constantly during the weekend. “This airplane really needs to come here and be with these airplanes and the people who love them,” Ricciotti says, adding that he values how easy it is to just get up and fly, as opposed to more congested and bureaucratic aircraft gatherings. “I fly more than five times a day here. I can go out and enjoy the airplane, and people can see the airplane flying, people can be in the airplane flying with me. I love it.”

Aircraft collector Greg Herrick and his friends brought three of his Fairchild PT trainers to last year’s fly-in. Herrick, who lives in Minnesota, grew up in Ottumwa and says the AAA fostered his interest in aviation. The rare aircraft in his large collection—he has also flown his Ford and Stinson Tri-motors to Blakesburg—all come from the 1920s and 1930s, one of aviation’s most innovative eras. “That’s the period of time that represented real aviation progress in this country,” he says. “Had we not had that kind of development we’d kind of be what Russia was [in World War II].”

Membership in the AAA is a requirement for attending the fly-in. (Visitors can sign up on the spot.) Almost all the people who fly to Blakesburg come in an antique—an aircraft with a type certificate dated 1935 or earlier—or a classic, a category for types certified from 1936 to 1941. A number of World War II-era and post-war “neo-classics” also show up. Modern airplanes are welcome, but their pilots can expect some gentle ribbing—and segregated parking. Of the 365 airplanes that showed up in 2015, 341 were what Brent Taylor calls “display” aircraft, the kind of vintage beauties that attract attention when they land at small airports. What makes antiques and classics popular with his organization’s membership, says Taylor, is hard to define, but it has something to do with how they’re built. Before the war, airplanes were made almost by hand; afterward, they were manufactured. “Modern airplanes, just like everything else [modern] in life, are homogenized,” he says. “They all fly about the same. You don’t get that with an old airplane. They’re more challenging to fly, and even though the physics are the same, going from a 1928 Stearman to a 1936 Rearwin to a 1939 Spartan—they’re enough different that there’s a challenge to fly them and fly them correctly.”

Older aircraft have other appeals, says Brent: “History has a lot to do with it. Nostalgia has a lot to do with it. In our organization, family history has a lot to do with it.” It goes like this, he says: “Grandpa had a 1928 Stearman or whatever and I rode it in when I was a kid, and that’s what I want.”

Taylor’s own family follows this model. When he was 16, Robert Taylor’s grandson Ben soloed in a 1941 Interstate Cadet, the same airplane his grandfather soloed in. Not the same type of airplane, the very same Cadet. It’s the airplane both Ben and his father Brent fly today.

The fly-in has always been a family affair for Harve Applegate of Queen City, Missouri. This year Applegate and his flying family brought three airplanes to the fly-in, including a 1947 Stinson 108-1 that has transported five generations of his family, including his daughter, Shalyn. Shalyn started flying when she was 18, and is embarrassed, she says, that she waited so long. At 20, she is a professional pilot with a multi-engine rating.

The Stinson looks remarkable, considering that the wings were last re-covered in 1966, the fuselage in 1979, and the door handles have the original plating. “These are the same seats my great-grandfather sat in,” Shalyn notes proudly.

The 2016 fly-in will celebrate this continuity, which sets the AAA/APM event apart from others. According to Brent Taylor, some families have four generations attending. This year, with the theme of “Back to Blakesburg/Back to Basics,” the association has put out a call to “Antique Airfield kids,” all those who were under 18 when they attended their first fly-in at Antique Airfield, starting with the first one in 1971. “We’ve already gotten a lot of interest from people who haven’t been here in a long time,” he says. “It was one of our more brilliant ideas—of the ones we wrote down,” he laughs.

One of the AAA local chapters—there are 19 around the country—is an organization of merry pranksters in LeSueur, Minnesota, who call themselves Marginal Aviation. They have been responsible for some of the practical jokes perpetrated at the fly-in over the years: hiding airplanes, alligator sightings, Christmas carolling in September until way too late at night, “rolling” airplanes with toilet paper, and pumpkin dropping.

The Marginal gang was started by Minnesotans Forrest Lovley and Gary Hanson; Gary’s son Toby has assumed the mantle of leadership. Toby also volunteers as one of the flaggers stationed on the runways who signal pilots “okay to land” or “go around.”

Every morning Brent Taylor, standing atop a picnic table, conducts a pilot briefing to explain how the system works: “Turn the damn radio off. Bernoulli flies the airplane, not Marconi. It’s red flag, green flag. Kind of like going through Mexican customs. If the red flag is up, continue your approach, but if they wave it, add power and go around. Once the airplane ahead of you has cleared the runway, the green flag will come out and you will make your landing. Do not stop on the runway, because there is likely someone behind you. If the two of you come together it makes bad noises and there is a lot of paperwork involved. Flybys are acceptable but absolutely no smoke on takeoff. The reason should be obvious. You just made the field go IFR [instrument flying rules] and the flag guys can’t see.”

On this hot and humid Iowa morning, Brent also needs to settle an important debate. “If you have to put the airplane off airport [he means crash], obviously your first choice is a hayfield and your second is a road. But the roads around here have high [power] lines. So you are down to corn and beans, and there is some argument. This time of year with mature beans, unless you got tall skinny tires like some of the real old antiques, you want to pick the corn. The reason being is that the mature beans are going to wrap around the landing gear, and 98 percent of the time you are going on your back.”

About 100 members volunteer every year to help the Taylors “keep the antiques flying”—the slogan painted in big script on the side of one of the hangars—at the annual fly-in, and various community groups participate as well. The women of the Blakesburg Historical Society sell homemade pie and ice cream. Ann Pellegreno notes with relief that the task of feeding the masses has been outsourced to the catering department of the local supermarket; in Blakesburg’s early days, women volunteers were in charge of provisions.

Beyond the fly-in, the AAA works to address issues seen as detrimental to the viability of antique aircraft. “The knowledge gap in the FAA is one of the biggest challenges we face going forward,” says Brent Taylor. “People are coming into the FAA who have no experience with old airplanes, no knowledge of them, and in a lot of cases don’t want to.” So Brent spends a fair amount of time working with other aviation organizations to address regulations, such as recent federal laws requiring all aircraft be equipped with certain types of modern avionics, seen as detrimental to antique aircraft. The AAA supported the efforts of member Greg Herrick to gain access to the drawings and technical data supplied to the FAA for the certification of the 1936 Fairchild F-45. Herrick wanted the information to guide the restoration of his F-45, but the FAA denied him the information, citing the need to protect trade secrets. After years of litigation, Herrick asked the AAA for help. The group won a Supreme Court case arguing for the right to view the drawings, Taylor v. Sturgill, and joined Herrick and other organizations to push for access to the drawings of other vintage aircraft. Herrick worked with pilot and U.S. Representative Sam Graves (R-Mo.) to amend the 2012 Federal Aviation Administration Re-Authorization Act to require the FAA to preserve and make available for non-commercial purposes all drawings for aircraft granted type certificates between 1927 and 1939. In aviation circles, the change to the bill is known as the “Herrick amendment.”

Herrick was concerned that some drawings were being either lost or destroyed. “Those drawings are the very DNA of aircraft development,” he says. “I’m personally interested in preserving airplanes from small manufacturers who went out of business or larger manufacturers where there were only one or two of a model left.”

The AAA has become the repository of some drawings, Brent Taylor says. “We have all the drawings here on microfiche for Stinsons, we’ve got all the Howard drawings, and a good portion of the Rearwin drawings,” plus other collections.

But some drawings may be gone for good. Shortly after the Herrick amendment passed, the AAA’s Steve Black, director of the Airpower Museum, tested it by requesting drawings for a Stinson 10 from the FAA’s Chicago Aircraft Certification Office. Says Brent: “We got the copies but found all kinds of things mixed up in it, including drawings for a Ryan ST,” a 1930s sport aircraft.

Some say that without Robert Taylor and the AAA, many of the vintage airplanes flying today would have themselves been lost. “There are about 30 of them out there in that hangar,” says Herrick. “He inspired me.”

The AAA still relies on its members for documents, and in most cases it doesn’t need to ask. Every week unsolicited boxes of drawings, books, manuals, and sometimes even airplane parts are delivered to the association’s library. “Some days 10 or 12 boxes just show up. It’s overwhelming,” says Black, who manages the library as well as the museum. “And you don’t know what you’ve got until you get in the boxes, and then sometimes you find really neat overhaul manuals on really old engines.”

Some donations come in after a member has died: The heirs pack up all the airplane stuff and send it in. The duplicates are sent to the museum gift shop, where they’re put up for sale. Besides the 6,000 volumes, the library has a large collection of manuals and periodicals. The basement is jammed wall to wall with boxes of them.

The occasional rare gem has surfaced. Black shows me a 1904 Curtiss Model 24 airship engine on display on the museum’s main floor. It had been donated more than 30 years earlier, and no one had paid much attention to it until recently. “We contacted the Glenn Curtiss Museum in Hammondsport, New York,” Black says. “They don’t even have one.”

As the afternoon fades, Robert Taylor reflects again on his friend Jack Lowe, and his generous early gift. He thinks the AAA could have survived without Lowe’s help, but it would have been difficult. Taylor says, “I probably could have muddled though here or passed [the association] on to somebody else or another organization…,” but he doesn’t think the Antique Airplane Association would be what it is today. “Not without Jack,” he says. Taylor turns in his chair and looks out his crow’s nest window at the gaggle of aircraft assembling on the grass below. “How lucky can an old man get?”

Six hours later, the late evening crowd has overflowed from the Pilot’s Pub onto the grass, and is gathering around campfires in front of the hangars. The victorious Hawaiian Shirt Night contestants proudly display their trophies—decorated coconut shells. The assembled revelers break into song:

’Cause if you stop in for a while,

You’re going to come out with a smile!

The ballad is actually about a brothel, but it could equally apply to a special piece of rolling pasture in Blakesburg, Iowa, thanks to the vision of Robert Taylor.