Portrait of the Enemy

Photographs taken from the world’s first warplanes changed the course of battle.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/AS08%20AerialRecon%20631x300.jpg)

The padded envelope arrived on my doorstep with an ominous thump. The return address, Knox Burger Literary Agency, confirmed my apprehensions: It was the manuscript I’d mailed to my irascible literary agent only a week before. Apparently, he hadn’t liked it.

Knox Burger had learned his trade during the Second World War, writing from Tinian in the Mariana Islands for Yank magazine. He flew on the B-29 raid that burned the heart of Tokyo to ash. He was one of the first journalists to walk that city’s streets after the war, and sent back a haunting interview with a Japanese fireman who’d tried to put out a firestorm with a bucket.

Knox was and remains almost impossible to please. Even worse, he’s usually right. So I wasn’t eager to tear open that package and see what he’d done to my manuscript.

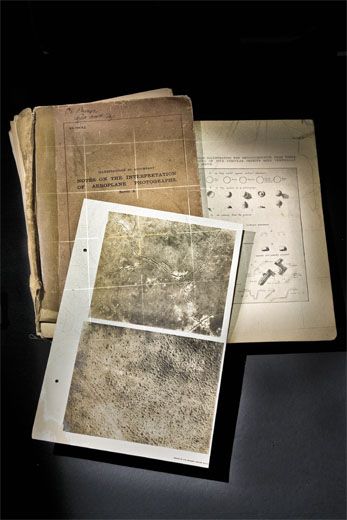

But I was wrong. Inside I found a large book of photographic plates: Notes on the Interpretation of Aeroplane Photographs, bound in heavy cardboard, peeling tape, and twine. It looked, even smelled, old. And in Knox’s spare, demanding style, a note: “I found this in my father’s things. Make sure it finds its way into the right hands.”

I’d researched modern intelligence gathering for a book about submarines, Hostile Waters, that I’d co-authored. But “aeroplane?” How old was this book? I opened it, taking care with the fragile binding. A handwritten label said the book had been issued in 1918 to Knox’s father, Captain Carl Burger of the 344th Infantry, United States Army.

I’ve seen stills taken from the Predator, a General Atomics unmanned aerial vehicle that flies reconnaissance missions over Iraq; the old plates in Captain Burger’s book were far sharper. Taken during the Great War, the photographs were astonishingly clear and detailed, showing shell-pocked moonscapes around the Somme River in France, trenches, and the tracks left by soldiers rushing to battle, as well as a chaos of trails made by men fleeing for their lives. In one, I could even make out a biplane rising up from an enemy aerodrome.

The accompanying text began: “In the British Army, the whole trench system of the enemy is photographed from a standard height of 6,600 feet at least once every ten days.”

Could “whole trench system” mean the entire Western Front, from the North Sea all the way to the Swiss border and beyond? That was 500 miles—a lot of flying, a lot of photographs.

The military’s view on aviation had clearly undergone a major shift. Only a few years before Notes was issued, General Ferdinand Foch of France had said, “Flying is merely a sport and from the military point of view has no value whatsoever.” When Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s 1914 assassination in Sarajevo sent the world to war, reconnaissance was conducted by cavalry—that’s right, men on horses.

As for aerial reconnaissance, early observers went aloft over France in tethered balloons armed with nothing more than sketchpads. Now, according to Notes, overlapping photographs covering half a continent were routinely shot from more than a mile high, with camera lenses that were good enough to show whether a trench was full of soldiers or mud.

Aerial reconnaissance, like aviation itself, had entered World War I as a primitive art. How had it become a science so quickly? A phrase in Notes provided a clue: “The disregard of aerial photographs has cost many avoidable disasters and useless loss of life.”

The Germans had laid out the conquest of Europe in great detail in the pre-war Schlieffen Plan, a strategy for conquering the continent by way of a lightning thrust through neutral Belgium, the capture of Paris, and, in six weeks, German forces on the English Channel. Like most such plans, it didn’t survive contact with the enemy. The quick war of maneuver bogged down to a bloody stalemate. One of the main reasons: aerial reconnaissance.

At the outbreak of fighting, on August 1, 1914, the French could muster 132 military airplanes. The British had 40 able to fly across the Channel. Though the Italians had been the first to use airplanes in war, sending Blériot XIs to Libya in 1911 to bomb, scout, and even photograph Turkish troops during the Italo-Turkish War, they were years from joining the conflict. The Russians planned to adapt Igor Sikorsky’s immense, four-engine Ilya Mourometz—a precursor to the modern airliner with a heated, lit cabin and bathroom—as a bomber, but at the start of the war, the Russian air force consisted almost entirely of aircraft imported from France, Britain, and Germany, sources that dried up at the first shot.

All military aircraft of the day served only as observation platforms, meant to augment the reconnaissance work of tethered spotting balloons. None was armed.

The first of the Allied scouts took off on August 19, 1914. They were hampered by typical summer weather: haze, heat, clouds, and thunderstorms. There were no charts, no navigation aids of any kind. The results were predictable. A British pilot left his field in northern France in a Blériot XI and promptly got lost, managing to fly directly over Brussels without recognizing it. A French pilot in another Blériot came down in a town that was still in Belgian hands and later reported back that “an excellent lunch was provided by the garrison commander.”

And the Germans? They had about 200 aircraft, split between the Eastern and Western Fronts, plus a secret weapon: a few aerial cameras with superb Zeiss lenses.

On August 22, the day when British and German soldiers first clashed, 12 British BE 2a biplanes (a 1913 design that, like the Wright Flyer, used wing warping to turn) were sent up to locate the enemy. They didn’t have to fly very far: an entire German army was marching south from Brussels, split into vast columns like the prongs of a pitchfork. The Germans had thrown the French forces back, and the British had been left alone and exposed.

The British commander, Field Marshal Sir John French, was an old cavalry officer who didn’t have much use for airplanes. When one BE 2a pilot reported what he’d seen, French stormed, “How do you expect me to carry out my plans if you bring me all these bloody Germans!”

Later, however, in a post-war memoir he admitted, “This was our first practical experience in the use of aircraft for reconnaissance purposes. The timely warning they gave enabled me to make speedy dispositions to avoid disaster.” The information from the aerial scouts allowed the British to maneuver out of the way of the seemingly unstoppable German advance. French saved his army.

A few weeks later, with Germany’s noose on Paris tightening and the government evacuating, Corporal Louis Breguet, flying an AG 4 he’d designed himself, discovered a gap in German lines. The French attacked, stopping the invasion just 30 miles from the city. With the war barely begun, aerial reconnaissance had already changed the course of battle.

On the Eastern Front, in the epic Battle of Tannenberg, the Germans paid attention to their scouting pilots; the Russians ignored theirs. The result: Between August 17 and September 2, 1914, an entire Russian army was destroyed, its soldiers killed or captured, its commander dead by his own hand.

As the value of aerial intelligence soared, stopping it became ever more critical. A pilot’s life, already endangered by bad weather, unreliable engines, fragile airframes, and anti-aircraft fire, was about to become a lot more dangerous.

On Monday, October 5, 1914, a north wind blew across the vineyards near Rheims in northern France. For the soldiers of the German Second and Third Armies huddled in trenches, the cold was proof that the Six-Week War they’d been promised had been ill-named. The men of the nearby French Fifth Army weren’t any happier, but at least they could suffer with bottles of the excellent local champagne.

The drone of airplane engines turned thousands of faces up to the sky. A German Aviatik, a two-seat observation craft, was approaching at 3,500 feet to survey French lines. A second aircraft, a French Voisin, was above and behind it.

Lieutenant Fritz von Zangen, the Aviatik’s observer, commanded the recon flight from the front cockpit. He had an artillery map on his lap. His pilot, Sergeant Wilhelm Schlichting, sat huddled behind him. It seems likely that neither one saw the Voisin swooping down into their “six.”

The ungainly two-man Voisin resembled a baby stroller with wings. It was returning from a bombing mission when its pilot, Sergeant Joseph Frantz, spotted the Aviatik. He dove on it, overshot, then banked back in.

First the French soldiers, then the Germans climbed out of their trenches to stare up at a most unusual sight: the world’s first dogfight.

When the war began, opposing airmen could only shake their fists at each other. They soon armed themselves with pistols, rifles, shotguns, even grappling hooks and hand grenades. But Frantz’s front seat observer, Mechanic Corporal Quenault, had something new: a Hotchkiss machine gun, and as the Aviatik grew large in his sights, he fired.

The German pilot tried to dive away but Frantz stayed with him. The French soldiers on the ground cheered. Then the balky Hotchkiss jammed. The two airplanes were just 600 feet above the ground. The frustrated French gunner pulled out a rifle, aimed, and fired. The bullet struck Sergeant Schlichting. The Aviatik flipped and crashed in a ruin of timbers and canvas.

A new chapter in warfare had begun. For pilots in fast, single-seat Fokkers armed with fixed guns, fragile kites with sputtering motors were meat on the table. The vulnerable reconnaissance airplane had to adapt or die. A Farman F.20 of 1914 cruised at 68 mph and could climb, on a good day, to about 8,000 feet; by 1918, the Italian Ansaldo SVA 5 reconnaissance airplane could climb to 20,000 feet and outrun the swiftest single-seat fighters. It was the SR-71 Blackbird of its day.

Cameras improved as well. The long lens of the British Type L enabled an observer to fly higher, out of the reach of “Archie” (anti-aircraft fire). Still, it was one thing to take a good aerial photograph and survive to bring it home, and quite another to train someone who had never seen the world from the air to make sense of it.

A photograph is a near-exact projection of the terrain upon a two-dimensional plane, and in the words of Notes, people without “air-sense” literally could not tell a haystack from a hole in the ground. France led the pack in photographic analysis. Capitaine Jean de Bissy published his Note Concernant l’Interpretation Methodique de Photographies Aeriennes a year before the war commenced. De Bissy’s pamphlet became the model for all subsequent aerial photographic training. It morphed into a number of longer, more detailed publications that, unlike the high-quality camera lenses they hoarded, the French willingly shared with their British allies.

Lieutenant J.T.C. Moore-Brabazon, who in 1909 had won London’s Daily Mail prize for the first all-British flight of a circular mile, tried to get someone interested in the French manual. He had a hard time. The new technology seemed rude. “The Army took the greatest exception to an enemy who indulged in dirty tricks,” he wrote in his 1956 memoir, The Brabazon Story. “Aerial photography invaded a privacy that had always been accorded an enemy.”

The war quickly rendered peacetime courtesies obsolete, and the British army published Notes on the Interpretation of Aeroplane Photographs, the English version of the original French book, in November 1916. When America entered the war the next year, Major James Barnes and First Lieutenant Edward Steichen—the former an explorer, the latter the most famous photographer of his time—surveyed French and British material on aerial photography. Together, they produced the copy of Notes issued to my literary agent’s father back in 1918.

So just how much do the plates in Notes reveal to an infantry intelligence officer like Captain Burger back in 1918? Quite a bit.

Where was the enemy? Take a look at how markings left by recently buried communications cables point, unerringly, to what we today might call a “command and control node.” What were the enemy’s strengths? Look how much information the analyst squeezed from one plate: billets for troops, hidden heavy guns, batteries of howitzers, even trucks on the road. What is the enemy up to? We see “No-Man’s Land” being prepared for an all-out attack: new “saps” (exploratory trenches) snaking out from German-held territory to foot trails left by daring British patrols.

The publication of Notes marked the end of aviation and aerial photography as primitive arts, and their birth as sciences.

Not that art and inspiration were completely banished. In a postwar memoir, Notes co-author James Barnes writes: “Interpreting aerial photographs demands a peculiar mind—the type that enjoys chess problems or crossword puzzles. To the uninitiated, a photograph of a line of trenches and myriad shell holes means very little. But to a puzzle solver, they tell a story. Often his imagination is set on fire by some puzzling little thing, the reason for which he cannot quite discover. Like a game of poker with aces up the sleeve, the battle between the camera and camouflage is on. And then, all at once, he has it!”

Today, the puzzle solvers can be found at places like the National Reconnaissance Office in Chantilly, Virginia, working to decipher images returned by U.S. reconnaissance satellites that continuously orbit over the world’s trouble spots. Despite the many advances in technology, these analysts know exactly what Barnes was talking about 90 years ago: the thrill of having your imagination set on fire by some puzzling little thing, and then, all at once, you’ve got it. The enemy is revealed.