The Time a Stolen Helicopter Landed on the White House Lawn

The story of Robert Preston’s wild ride.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/68/16/68169118-31d8-49ce-92e8-577045a2f8a5/04g_am2017_gettyimages-515112550_left.jpeg)

Landing a helicopter on the White House lawn is a rare privilege, usually reserved for only the most experienced and trusted pilots, but in 1974, a 20-year-old private first class with 157 hours, no rotor-wing certificate, and a wrecked love life decided to take a run at it—while being chased by police and shot at by the Secret Service.

Robert Kenneth Preston was born in 1953 in Panama City, Florida, and as a high school student enrolled in the Junior Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps. He competed in intercollegiate aviation events, earned a private pilot’s license, and later studied aviation management at Gulf Coast Community College. His dream was to become a military “dustoff” pilot, evacuating wounded soldiers in Vietnam.

Preston enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1972, joining a four-year program that guaranteed him two years of helicopter pilot training in return for two years of post-training enlistment. At flight school in Fort Wolters, Texas, Preston flew the Hughes TH-55 Osage, but washed out of the program because of “deficiency in the instrument phase,” losing his chance to become a warrant officer and effectively ending his flying career before it began. Preston believed his situation unfair, a byproduct of the ongoing U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam, which left the Army oversupplied with qualified helicopter pilots. Still, bound by his contract with the Army, he would have to stay in the service for all four years. He was transferred to Fort George Meade in Maryland, nearly 20 miles northeast of Washington, D.C., to begin training as a helicopter mechanic. His commanding officer there described him as a “regular, quiet individual” of above-average intelligence.

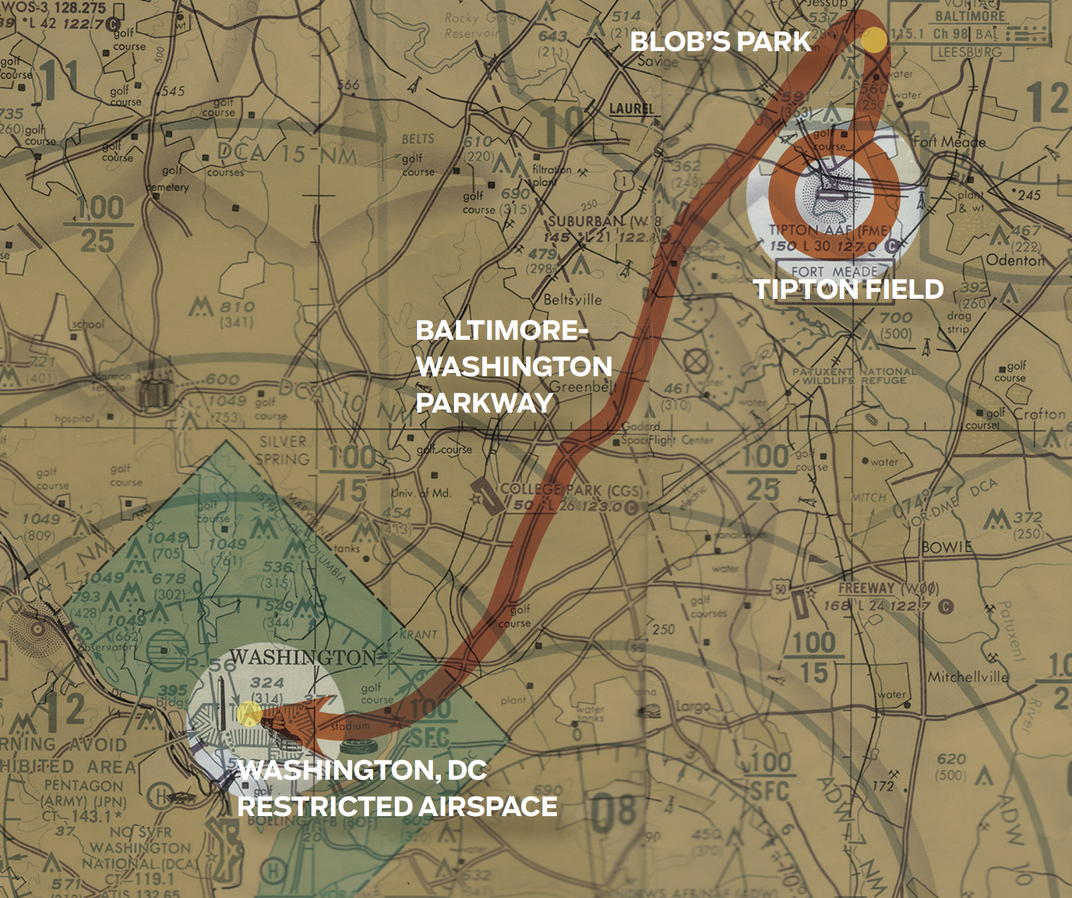

Shortly after midnight on February 17, 1974, the 20-year-old private, despondent over his muddied future and a failed relationship, was on his way back to base from a local restaurant and dance hall, and decided to return to a place that had always brought him happiness: the sky. “I wanted to get up and fly and get behind the controls,” he said later. “It would make me feel better because I love flying.” At Fort Meade’s Tipton Field, thirty Bell UH-1B Huey helicopters sat fully fueled, ready for the Reserve and National Guard units that trained there.

Preston drove his car onto the unguarded airfield and parked. “I just walked out, prepared the aircraft for flight, started it, and took off,” Preston later said. “I was really surprised. I thought there would be somebody out there.”

By the time a sentry noticed Preston’s green Chevy Nova parked in an unauthorized area, the Huey’s rotor was turning. Shortly thereafter, Preston lifted off without making any of the standard radio calls or using the anti-collision lights. Even without the Huey’s lights on, a dispatcher in the control tower saw the helicopter take off and quickly realized there were no current flight plans on file. He called the Maryland State Police.

Patrons at Blob’s Park restaurant, where Preston had been earlier (drinking only soda, an acquaintance told the FBI), also called the police, reporting that a helicopter had roared by just a few feet above the roof, hovered momentarily, then buzzed over houses nearby. Others called from a trailer park in the nearby town of Jessup to say that the helicopter touched down nearby, then lifted off and flew away.

After he buzzed Jessup (a local later found Preston’s Army hat in a field there), Preston decided that he had a great perch from which to take in the sights of the nation’s capital, only 20 miles to the southwest. Guided by the lights of the Baltimore-Washington Parkway, he headed toward the National Mall.

Going Rogue

Police in the District of Columbia first learned of Preston’s helicopter when they saw it flying between the Lincoln Memorial and the Capitol building. Flight there was strictly prohibited in 1974, as it is today. At the time, aside from radar surveillance, the boundaries were not physically enforced in any meaningful way. (Following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, surface-to-air missiles were installed in a ring around Washington’s airspace.)

The Washington Monument was floodlit and prominent, as usual, and Preston flew toward it “like a moth to the candlelight,” he told the military judge at his court-martial. He turned on all his external lights and leveled off a few feet over the monument’s expansive grounds.

After he’d spent about five minutes taking in the Washington Monument, Preston flew to the Capitol, and then followed Pennsylvania Avenue to the White House, which he said he identified as “a big black spot” in the middle of a sea of lights.

At the White House Executive Office control center, Secret Service agent Henry S. Kulbaski, the watch commander on duty, was notified that an Army helicopter had been stolen and was headed for the restricted airspace near the White House. (Coincidentally, in his youth Kulbaski had worked for Bell Aircraft Corporation, which built the UH-1.)

As the pilfered Huey hovered near the Washington Monument, Kulbaski tried to reach his superiors on the phone and peered into the pre-dawn sky, searching for movement. Though Secret Service policy was to shoot at aerial intruders, just how and when to do so was left vague, especially if it might endanger bystanders—a distinct possibility if the shots downed a helicopter flying over a major city. But Kulbaski’s superiors were unavailable, he said, and as he tried to reach them, Preston leveled off over the White House’s South Lawn.

“Everybody just stood around looking,” Preston later said in court, and after 10 minutes he decided that “if they weren’t going to do nothing I was going to leave.” Kulbaski watched the helicopter hover, then retreat. “[W]hen no one answered,” he recalled, “I knew I had to make the decision myself.” If the Huey came back, he told the protective agents on duty, be prepared to shoot it down.

The Chase

At 12:56 a.m., an air traffic controller at National Airport spotted a blip on his radarscope. Having received a warning about a stolen helicopter from the Federal Aviation Administration’s Baltimore office, he realized the blip was the stolen Huey. The controller called Washington’s Metropolitan Police Department and asked them to intercept the helicopter with one of their own. But the blip on his screen, after hovering in the prohibited airspace next to the White House, followed the Baltimore-Washington Parkway back into Maryland. MPD’s old Bell 47G helicopter followed, but was not fast enough to keep up. As Preston returned to Maryland, controllers at Baltimore/Washington International Airport picked up his radar track, and the Maryland State Police dispatched two Bell 206 JetRangers to pursue him. Piloting one of them were Donald Sewell, a decorated Vietnam combat pilot, and copilot Louis Saffran.

Around Maryland they went, Preston and the Maryland State Police, in an aerial game of cat-and-mouse. On the ground, police cars followed. Preston chased one off the road with a head-on pass just inches over its roof, hovered briefly over a doughnut shop (where, he later said, he planned to give himself up, but could not find a spot to land), and overflew the Baltimore/Washington Airport. Finally, Preston realized there was no escape. He considered flying back to Fort Meade, but rationalized: “If I went back to the Army, they’d just put me in a stockade.” His best bet, he decided, was to give himself up to President Richard Nixon in person, and to do that he had to return to the White House. He again picked up the parkway and headed southwest.

After flying low along the Anacostia River, then again circling the base of the Washington Monument, he flew back to the White House, evading one of the two state police helicopters with what admiring pilots described as “modern dogfight tactics.” Only Sewell and Saffran were left on his tail.

“It was very hard to keep track of him, so Louis and I were both in constant aggravation trying to keep an eye on him to know where the hell he was going,” said Sewell. “He flew [at] erratic speeds ranging from 60 to 120 knots, and altitudes sometimes only inches above car-top level.”

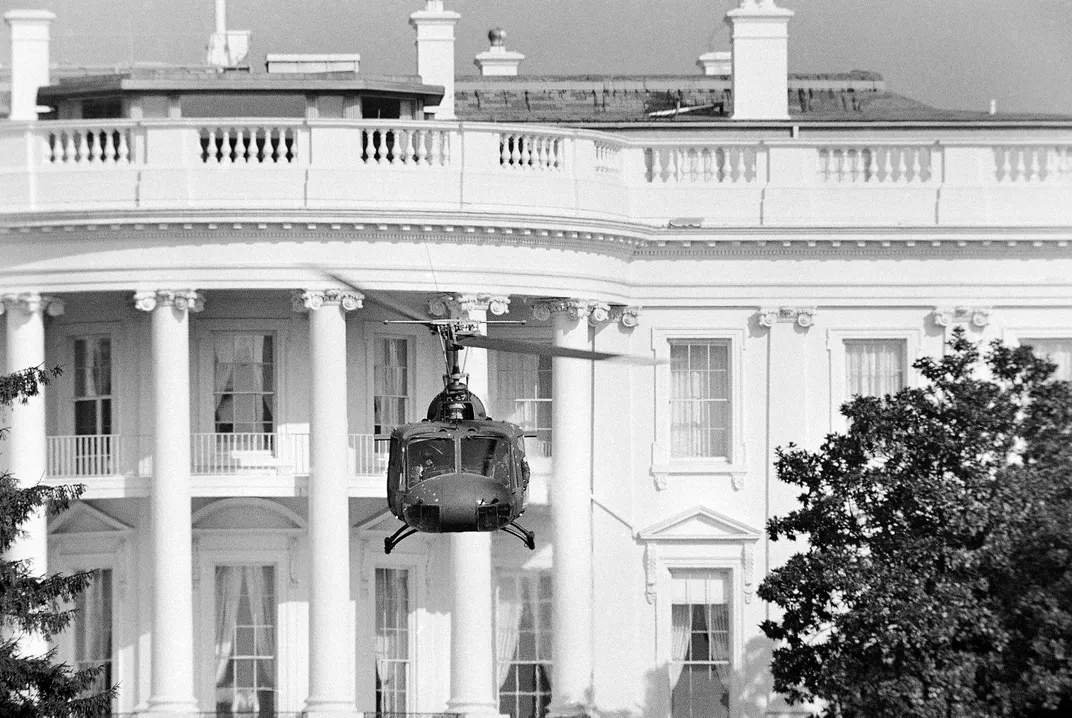

Preston came roaring onto the South Lawn for his second landing, just high enough to clear the steel picket fence, as Sewell and Saffran prepared to put their helicopter between the Huey and the White House. According to Saffran, Preston was so close, he “could have driven right in the front door.” The Huey approached the White House lawn about 120 yards from the building’s entrance. Kulbaski commanded his security detail to open fire. Floodlights snapped on and the Secret Service opened up on the Huey with shotguns and automatic weapons. The bullets blasted half-dollar-size holes in the helicopter’s aluminum skin. Some buckshot hit Preston’s foot and the Huey veered left, bouncing on one landing skid, then the other. Preston quickly regained control and, according to agents on the ground, “did a marvelous job of recovery” as the Huey settled gently onto the lawn barely 100 yards from the executive mansion.

As the Huey came to rest, Sewell and Saffran’s helicopter landed between the downed aircraft and the residence. Saffran jumped out to see a lightly wounded Preston open the Huey’s door, roll under the helicopter, and start running toward the White House. He was tackled by Secret Service agents. Saffran ran up to Preston, verified that he was securely in custody, then returned to his own helicopter and left.

MPD Sergeant Thomas F. Linnehan saw the Huey land. “They said he couldn’t fly. Well, I’ll tell you he could fly,” Linnehan told the military court. “If he had not harassed the citizens of the state of Maryland as he did, and had not made such a big show of it…the man could have flown directly into the White House at 160 knots and there wouldn’t have been anything anybody could do.” Faced with that dire possibility, the Secret Service’s only (publicly known) response was to slightly increase the size of White House restricted airspace.

Over 300 rounds had been fired, but only five struck Preston, and his wounds were superficial. Handcuffed, Preston was taken into the White House for questioning, where the first agent to speak with him was Secret Service member Donald Lawton. When he asked if he could speak to the president, Preston learned that Nixon and his family were out of town.

The Secret Service took Preston to Walter Reed Army Hospital for treatment overnight, where he entered smiling and “laughing like hell,” according to wire service reports. He was later taken to D.C. Superior Court for a brief arraignment, then to the Walter Reed psychiatric ward for evaluation.

As daylight broke, the damaged Huey became a major tourist attraction. Army personnel arrived to evaluate the helicopter and found it flightworthy in spite of its many new bullet holes, and shortly before noon—in front of reporters and cameras from the major TV networks—the Army flew it back to Tipton Field, where it was locked inside a hangar as evidence.

The Price

Preston was initially charged with unlawful entry upon White House grounds, a federal misdemeanor carrying a possible six-month jail term and a $100 fine. But at his arraignment, his lawyers negotiated a plea bargain that dropped all the civil charges if he surrendered to military officials, who would follow through with a court-martial. A young captain in the Army Judge Advocate General (JAG) Corps, Hebert Moncier, represented Preston in court. “He was a very bright kid,” Moncier later recalled.

At court-martial, Preston was charged with the attempted murders of President Richard Nixon and the crews of both Maryland State Police helicopters that chased him, on top of a litany of lesser charges. “He was looking at a dishonorable discharge, and [a sentence of up to] 105 years,” Moncier said in a 2014 newspaper article.

But it was evident that Preston never expressed any wish to harm the president. Though at least one of Preston’s colleagues told the FBI that Preston intended to commit suicide in spectacular fashion, and a Secret Service agent who interviewed Preston said the same in court, Preston maintained that he just wanted to draw attention to the unfairness of his enlistment situation. After legal negotiations, Preston pleaded guilty to wrongful appropriation and breach of peace, which carried a total maximum sentence of two and a half years of hard labor plus a dishonorable discharge. The judicial panel recommended that Preston be sentenced to six months in prison, and it gave him credit for time served while awaiting court-martial. After two more months in military prison, Preston was released, underwent retraining, and given a general discharge.

Nixon soon returned to Washington, where he congratulated Kulbaski for issuing the order to down the helicopter, as well as troopers Donald Sewell and Louis Saffran for their valiant pursuit of Preston’s helicopter. At a White House ceremony, the president presented Kulbaski, Sewell, Saffran, and the other agents pairs of presidential cufflinks. (Six months later, Nixon resigned the presidency.)

Epilogue

After his release from prison, Preston moved to Washington state. He married in 1982, and raised two stepdaughters. He led a quiet life, working at a series of odd jobs and finding solace in religion (he was the subject of a segment on the fundamentalist Christian television show “The 700 Club”). Preston died of cancer on July 21, 2009, in Ephrata, Washington.

Since Preston’s flight, only once has anyone penetrated White House security using an aircraft. Around 1:50 a.m. on September 12, 1994, 38-year-old truck driver Frank Eugene Corder crashed a stolen Cessna 150 into the South Lawn, just a few feet short of the White House. He died in the crash; no one else was hurt. Corder had led a turbulent life, including several brushes with the law, and after a quick series of hard blows—his marriage crumbled, his father died, his business collapsed—Corder was living out of a motel in Aberdeen, Maryland, reportedly smoking crack cocaine and drinking heavily. After an evening of intoxication on September 11, Corder stole a Cessna 150 from Harford County Airport, just south of the Pennsylvania state line. Like Preston, Corder had had some flying lessons, but no license to fly the aircraft he was piloting. He managed to fly the Cessna over Washington, D.C., unnoticed. Corder flew north over the Washington Monument, turned over downtown Washington, and dove into the White House’s South Lawn. Unlike Preston’s attempt, Corder’s gave the Secret Service agents on duty barely enough time to dive out of the way of the aircraft. Security protocols had been significantly updated since Preston’s flight: the restricted airspace was expanded, and Stinger surface-to-air missiles reportedly added, but they didn’t stop Corder.

After its return to Tipton Field, Preston’s Huey was extensively photographed for the criminal investigation, then repaired for return to service. Dubbed the “White House Special,” the Huey was eventually transferred to the Pennsylvania Army National Guard for use as a ground maintenance trainer. Today the helicopter sits on static display at Joint Base Willow Grove in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, where the Guard trained their maintenance troops. No plaque or note alerts passersby to the Huey’s unique history, but careful observers might notice that the helicopter is covered with metal patchwork; whether they repaired a student’s errant wrench or holes from Secret Service-issue bullets is lost to history.