Racing Drones

With 40 million fans, $100,000 purses, and crashes galore, drones take the track.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c2/97/c297b212-8d18-417a-994a-377586688c7a/05c_dj2017_ribcageohio1_live.jpg)

Zachry Thayer expected that the competition for this drone race would be intense, so he just tries to be in the moment, to focus on the routine: video and power checks, safety clearance, and then the countdown—and they’re off! Six 800-gram quadcopters spring into the course. Thayer and his competition are wearing goggles that receive a video feed from cameras mounted on their drones, giving them a first-person view, or FPV.

The drones zip over my head in the spectator stands sounding like Formula One cars made hysterical by helium.

But I barely notice. I’m “in” one of the drones using my own pair of FPV goggles, streaking at nearly 80 mph over the nets that protect the spectators, through the first check gate—a neon circle—then banking a 90-degree left over a reflecting pool, and down the straightaway that runs the 300-foot length of the building. Then the drone shoots up, loops around two walkways, drops down through the first difficult obstacle, and then it’s spinning, then upside down—suddenly the screen in my goggles goes black. My drone, or rather the one I was following, has crashed. I take the goggles off, feeling a bit shaken but energized, as if I’ve just finished a roller coaster ride.

“This course required new things,” Thayer says after the race. “We had to fly slower in some parts in order to have enough battery for the technical parts.” Better known in the sport as A_Nub, Thayer is one of the top drone racers in the world. He won the U.S. Drone Nationals just the week before, and helped represent the United States at the World Drone Racing Championship in Hawaii.

The Drone Racing League—a startup backed by $12 million in venture capital from notables like Miami Dolphins owner Stephen Ross and Matt Bellamy, the lead singer of the British alt rock band Muse—are betting that they can translate this FPV thrill ride into a video experience that millions will pay to watch. Drone racing, barely a couple years old, is “blowing up,” in the tech dude idiom of the sport. In barely two years, it’s expanded from a few guys bombing line-of-sight loops in local parks to at least 100,000 FPV hobbyists worldwide (there are no central databases for the new sport, so the numbers are fuzzy).

Drone racing grew out of a convergence of several improving technologies: tracking equipment from smartphones, better virtual reality systems, the miniaturization of cameras and batteries. Those advances brought the price of drones (or unmanned aerial vehicles) down to an affordable point. A beginner drone racing setup goes for about $500, and an awesome one for less than $1,000. According to Dronelife.com, estimates of the number of drones sold in 2015 range upward of one million, so the number of hobbyists could be much, much higher.

The rapid growth has spawned a gaggle of competing leagues and formats. They’re all trying to turn this hobby into a real sport, with sponsorship deals, codified rules, and broadcast partners. (There appear to be plenty of investors for electronic sports, a euphemism for competitive video gaming, which in just a few years went from nerdy niche to global phenomenon.)

In addition to DRL, there are at least three other large U.S.-based drone leagues: The MultiGP-Drone Racing League claims more than 10,000 registered pilots and more than 700 chapters worldwide. The Drone Sports Association sponsored its own U.S. National Drone Racing Championships in 2015 and 2016, and brought pilots from more than 40 countries to its World Drone Racing Championships in Hawaii in October, all of which were live-streamed by ESPN. The Aerial Sport League plans to open its Tron-inspired Drone Sports World entertainment complex in San Francisco, featuring instruction, races, drone combat, and a store. DJI, a Chinese drone maker, has just opened a similar arena south of Seoul, South Korea. The International Drone Racing Association promotes drone racing worldwide.

Most pilots compete in several leagues. Travis McIntyre’s trajectory is pretty typical. McIntyre, 30, started in local races about 18 months ago, won a few, went to the first drone nationals, then became involved with DRL and eventually quit his day job (working at a department store) to race and train full time.

“We were wondering how many people would tune in to the first race,” says Nick Horbaczewski, the CEO and founder of DRL, talking about the league’s January event in a Miami stadium. “About 860,000 tuned in for the live race. When we released other content clips and highlights...about 40 million watched.”

Competitions are attracting big money: The crown prince of Dubai, along with several Dubai companies and the United Arab Emirates’ transport authority, put up $1 million in prize money for the World Drone Prix in February, paying $250,000 to the English teenager who finished first in the race there. The winner of the U.S. National Drone Racing Championships in July took home $10,000 in prize money, and $100,000 went to the various winners of the World Drone Racing Championship in October. The leagues are experimenting with various ways to fund the sport: MultiGP relies upon sponsorships from the U.S. Air Force and manufacturers of drones and FPV goggles. The USDRA and DRL are pursuing broadcast partnerships to fund their events.

**********

“It’s moving so fast,” says Thayer, who won the 2016 Nationals, placed sixth in Dubai, and competed at the Worlds in Hawaii. “I never imagined that I would be doing this, traveling, flying. It’s awesome.”

In the midst of this chaos, DRL hopes to set itself apart by focusing on post-production editing that weaves together compelling pilot stories, commentary, and themed races; their main approach will not be to show the races live, but to show packages after the fact. The league announced partnerships with ESPN and international broadcasters; they’ve also signed a content partnership with MGM Television and reality-TV producer Mark Burnett. DRL says it will release nearly 10 hours of programming before the end of 2016, and much more in 2017. The league’s Los Angeles race last March, LA-pocalypse, took place in the gritty, graffiti-covered halls of an abandoned mall in Hawthorne, California.

I’m at the July race, dubbed Project Manhattan —they couldn’t use “Manhattan Project” for legal reasons—and it evokes a high-tech factory gone wrong. Fog machines exhale on the course, and neon accentuates many of the check gates. Along the straightaway they’re calling the Ribcage, several ominous robot mannequins stand in what look like Borg alcoves from a Star Trek movie.

All this has been set up in the main building of Bell Labs, a legendary research campus in the middle of central New Jersey. The building, about eight stories high, houses a giant core atrium. If laid on its side, the Empire State Building could fit in this interior space.

Most pilots I spoke with were sucked into drone racing after viewing a 2014 YouTube video of a race through a French forest, which evokes the speeder bike chase in the forest in Return of the Jedi. Who wouldn’t jump at a chance to race like that, even if only through FPV goggles?

Between heats at the DRL event, pilots huddle around laptops with friends, sponsors, and coaches on man-cave leather couches, deconstructing videos of the latest heat, or the latest drone sensation on YouTube. Guys—virtually no women are here—high-five, sip bottled water, and laugh. Even with big money at stake, the competitors seem at ease giving one another tips and advice. Most drone racing pilots seem unusually cooperative and willing to help out the newbies.

“The drone racing community is extremely close,” explains Tony Knittel, whose race name is Kanoodle and who has been brought in as a kind of Bob Costas to announce for the Project Manhattan DRL event. “This sport evolved from the hobby world, which is a wonderfully helping community,” he says.

Zachry Thayer (A_Nub), Jordan Temkin (Jet), and Travis McIntyre (m0ke) live together in a rented farmhouse outside Fort Collins, Colorado. They’ve turned the enormous basement into a tech workshop. They practice together in their one-acre yard, or zip their drones around the cliffs and peaks of the Rocky Mountains. Sometimes Thayer and Temkin compete together as Team Big Whoop, as they did at the Dubai World Drone Prix and Drone Worlds in Hawaii. All three competed at the DRL Project Manhattan race.

“None of us got into this for anything other than fun,” says Thayer. “We’re working together to grow it.”

YouTube and Facebook host growing communities of drone racers; message a top drone pilot on social media, he will most likely answer.

“The learning curve is pretty steep,” says Trace VanGorden (Von Quad), the host of the Quad Talk FPV Drone podcast. “It encompasses so many different mediums of science, aerospace, programming, engineering—you can go pretty deep in the water when you start.”

“I love the tech, being able to engineer my own parts,” says Thayer, who designs and sells racing drones.

**********

Engineering savvy can give can give competitors an edge in races in which pilots design and fly their own drones. Most race quadcopters, but some race drones with three or (more rarely) six rotors. In some races, the drones would be dangerous if you got in their way; an Australian group just claimed that their 66-pound, five-foot-wide racing drone bested 200 mph. Others are small enough to fit in your palm and safe enough to buzz around a bar.

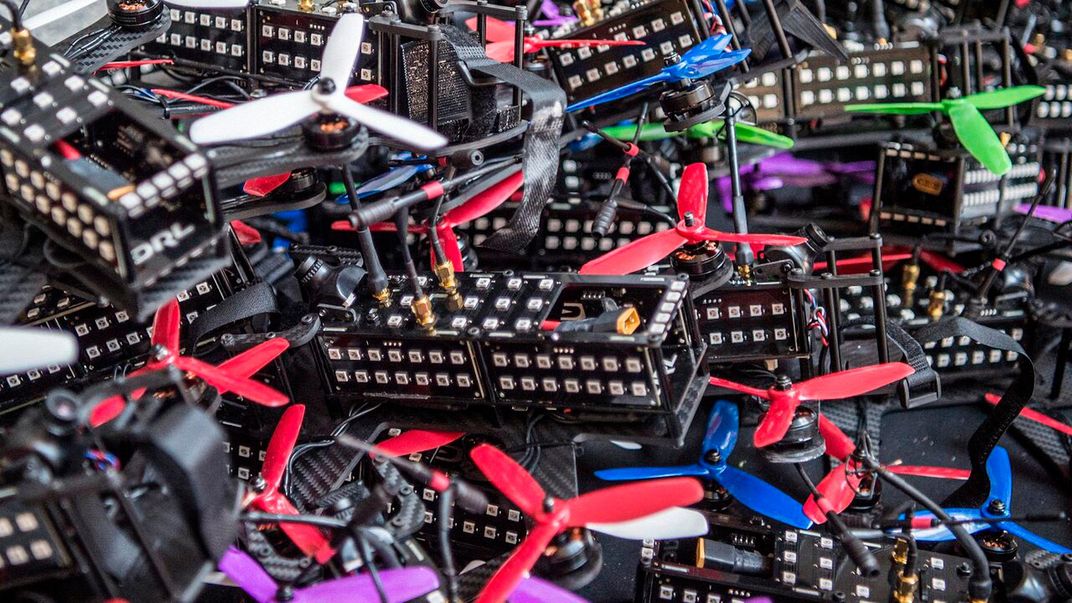

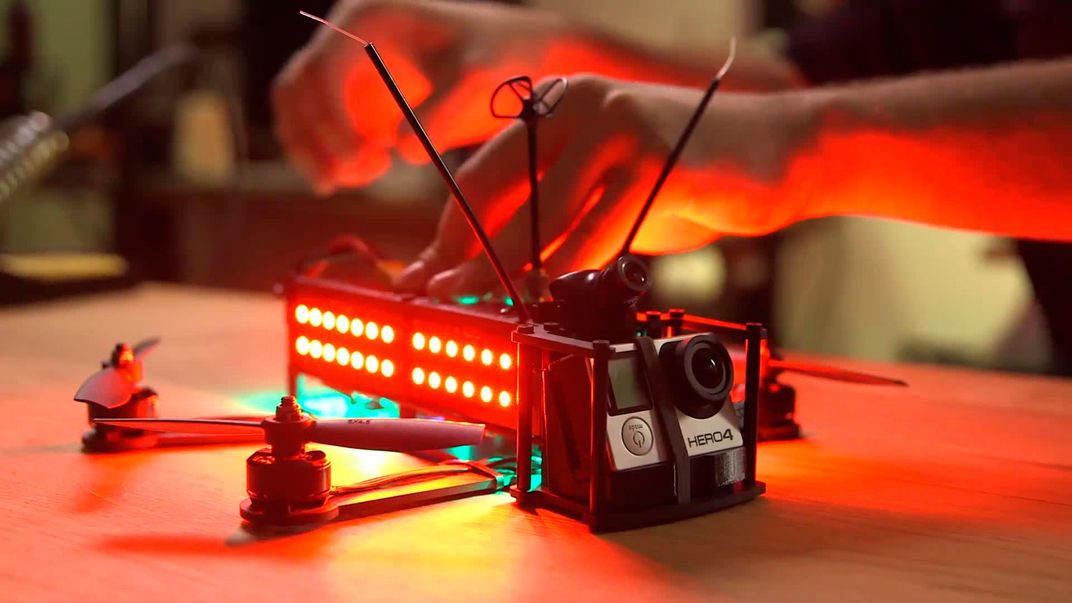

DRL differs from most other leagues in that all pilots at its events use proprietary DRL quad drones. Just before one of the heats, a DRL exec takes me back into the pit behind the race officials and the pilot stands. Dozens upon dozens of DRL drone bodies have been laid out in ranks on several tables: each an LED-bedazzled black carbon-plastic brick housing a battery and four arms extending from the corners for the rotors. A few engineers are repairing drones that crashed in the last race. Others are sifting through piles of rotors; still more people are getting drones ready for the next race.

At almost two pounds, DRL drones weigh more than most racing drones, but they’re also more powerful. With all pilots racing with the same type of drone, the competition focuses on piloting skills alone. The DRL drones are built to be sturdy, so they don’t break as easily as commercially available models. And because the pilots aren’t racing drones they own, they’re more likely to take risks. There’s no financial downside to just going for it.

“The fact that they’re on the heavier and larger side brings out the best racing I’ve ever seen,” explains Thayer. “By limiting the performance of machine, it forces a pilot to be a better pilot, to be the best they can be.”

The main obstacle in this multi-level Bell Labs race is an eight-foot-wide open cube that DRL has dubbed the Atom. In order to follow the course, each pilot has to do a split-S maneuver, swooping into the cube, flipping over, then swooping out in the opposite direction, thereby “splitting the Atom.”

I stand with DRL’s Nick Horbaczewski in the middle of the Bell Labs atrium, at a line of police barriers and nets that bisects the course, keeping people from getting in the drones’ way. Safety is a top concern; rotors can slice quickly and some pilots even carry QuikClot, a coagulation agent, in their backpacks. Behind us sit the pilots, the pit, and race officials. In front of us, the Atom has been suspended a couple stories up.

Horbaczewski, who previously worked at the extreme sports company Tough Mudder, looks like he’d be just as comfortable backpacking in Yosemite as running a race in this high-tech arena. We lean on the barriers and watch a couple heats. The pilots have to let their drones fall through the top of the Atom cube, flip, then punch the speed to get out of the bottom, while also managing to avoid slamming into the atrium floor. Even to the uninitiated, it looks difficult. Damn near impossible, really. And that’s the point.

“One of the things that people love is crashing,” Horbaczewski explains. “We knew that the Atom would cause a lot of crashing. In drone racing, there’s none of the moral hazard of Formula One racing. No one dies.”

Drone racing controls aren’t as easy as a phone app that levels and flies a camera drone; it’s much more hands-on and difficult. Pilots hold a thick control console and manipulate two small joysticks. The left stick controls throttle and yaw; the right controls pitch and roll. Drones have no rudders or ailerons; altering the speeds of the rotors changes the drone’s direction, attitude, and speed. When flying down a straightaway, they fly at a backslash angle, as the back rotors push the drone along.

“It’s like an Indy car in the air,” explains Knittel, the announcer. “It’s not going to just hover around and get groceries.”

Yet as the drones whip around the course like angry bees, the six pilots in each heat sit straight-backed and still. They could be Zen monks, but instead of meditation cushions they have funny goggles. Their only perceptible movement is in their thumbs, twitching ever so slightly.

As at the top levels of so many sports, it really comes down to psychology, the ability to perform under pressure. “Hand shakes” is a problem most pilots say they have experienced. Walking past the pilot rest area, I hear a coach advising, “Stay calm; don’t worry about trembling. Remember it’s just a game.”

“M0ke” McIntyre says that drone racing for him is “an out-of-body experience.”

“When I’m flying and have the goggles on, I’m so focused,” he explains. “I won’t hear the music in my headphones. I escape reality. It’s like being a little bird flying around in the sky.”

The tough bit is taking that pilot experience and making it accessible to a mass audience. DRL has released a multi-player drone racing video game, and many in the field think that someday it might be possible for viewers at home to “follow” a pilot in FPV goggles, just as I did at Bell Labs. Obviously, that tech will take a while to develop. For instance, the goggle feed now is grainy, because anything crisper would create a time lag greater than 20 milliseconds, the max allowable for racers to react in real time. For now, watching a drone race in real time is a bit like going to the horse races. There’s a lot of waiting, and each heat seems to be over in moments. And for a drone race to get off the ground, a lot of tech has to work right. Radio frequencies can interfere, or “stomp” each other. In some leagues, Knittel and other pilots say, races frequently get off schedule. Races can be an adrenaline rush, but in between there’s a lot of down time. There’s also the problem of high expectations. We’ve all gotten used to the thrilling CGI video of Harry Potter Quidditch and Star Wars pod racing. But think of actually trying to film something similar in the real world: How do the cameras get up close to things that are moving so quickly and so unpredictably? How do they do this over a large course?

At this point, DRL is relying on the drone cameras, 35 stationary cameras around the course, 360-degree video, and skillful film editing by a team of videographers.

Sitting in the stands, I watch as one drone ditches in the fountain soon after lifting off. Another two looping from floor to floor crash. Two more collide trying to get through the Atom. Not one of the six drones from that heat finishes. No matter. The next heat will see six more whiz into the air.