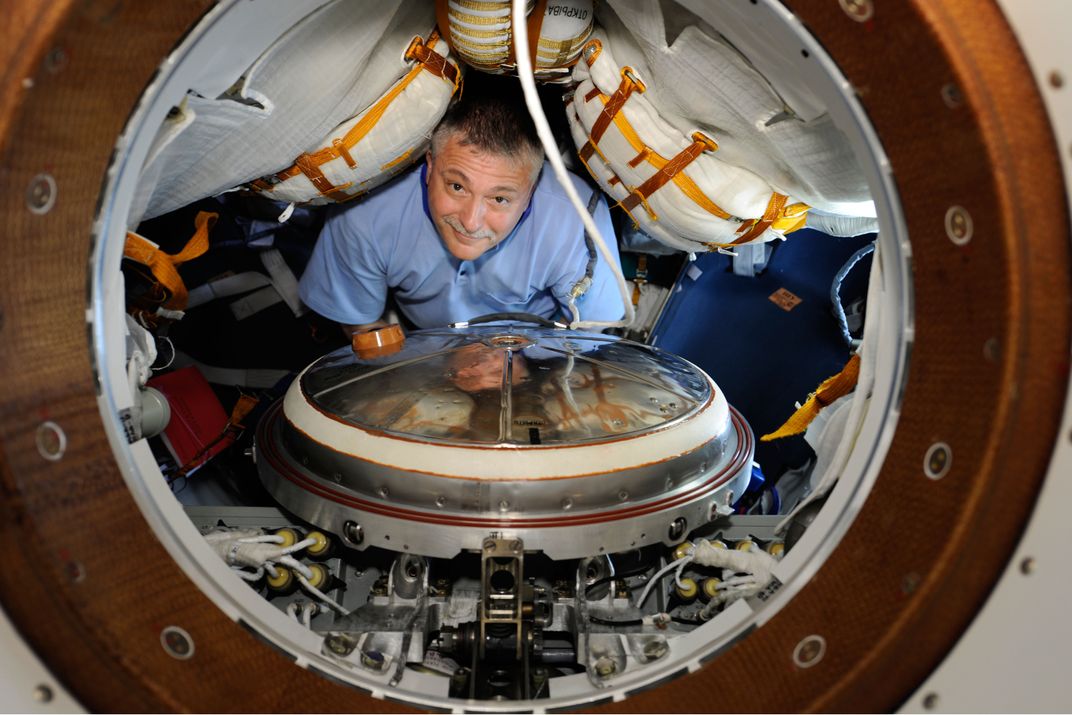

A Rare Look at the Russian Side of the Space Station

How the other half lives.

:focal(2144x878:2145x879)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b7/16/b7163554-16de-4e64-a7f5-8c3d576a362b/01j_sep2015_socks_say_max_live.jpg)

“A big hello from all on board the International Space Station!” cosmonaut Maksim Suraev greeted his country in October 2009 when he launched the first Russian-language blog from space. For the first time cosmonauts were speaking directly to the Earthbound (NASA had gotten astronauts on Twitter a few months earlier), and the blog was a refreshing counterpoint to communications from the Russian Federal Space Agency (Roscosmos), which offer little information about what the cosmonauts are doing. Suraev’s successors have continued the blog and, despite some inevitable self-censorship and political correctness, have finally offered a small peek into life on the Russian side of the space station.

Although the partner space agencies—in the United States, Russia, Europe, Japan, and Canada—work hard to portray the station as a harmonious home without borders, where astronauts and cosmonauts seamlessly cooperate on a common goal, Westerners really only see the activities on the U.S. side. The daily life of cosmonauts has stayed mostly hidden. Even architecturally, it is a divided station: On one side of the long, segmented truss is the U.S. segment with the European and Japanese laboratories attached; on the other side, at the far end of the Russian-built, U.S.-bought storage and propulsion module Zarya (Sunrise), is the Russian module Zvezda (Star).

Zvezda provides living quarters for the Russian crew and works as a space tug for the entire outpost, steering it, as necessary, away from space junk and compensating for the constant drag of the upper atmosphere. It also provides a powerful life-support system that works in tandem with the system inside the U.S. lab, Destiny.

Inside their Zvezda home, the cosmonauts have turned the module’s aft bulkhead into a wall of honor on which they put photos and mementos. A careful student of Russian culture could monitor certain political moves by watching the changing images on the wall, which serves as a backdrop for crew photos and ceremonial broadcasts. The Soviet-era Salyut and Mir stations had similar walls, and naturally this prominent spot was often adorned with portraits of Vladimir Lenin and other Communist leaders. Sharp-tongued space engineers dubbed this spot “iconostasis,” referring to a wall in Russian orthodox cathedrals where icons of the saints are displayed. The nickname has turned out to be prophetic.

For more than a decade, the wall on the post-Cold War Zvezda featured politically neutral photos of Sergei Korolev, the founder of the Soviet space program, and Yuri Gagarin. Around the time Russia annexed the Ukrainian territory of Crimea in March 2014, the wall had been undergoing a transformation. The Russian Orthodox Church, which has long had a broad influence on the country, including spacefaring activities, quickly spoke out as one of the most ardent supporters of the ultra-conservative and nationalist policies adopted by the Kremlin. In 2014, Crimean-born cosmonaut Anton Shkaplerov, now a symbol of the Russian space program, made a widely advertised visit to his homeland before his flight to the station. Upon his arrival at the station in November, photos of Shkaplerov and his crewmates showed a backdrop of Orthodox icons and crucifixes—Korolev and Gagarin had been moved quite literally out of the picture.

Downsized and Deferred

As blueprints were being drawn for the International Space Station, the Russian plan was to assemble several research labs to attach to Zarya and Zvezda, but those labs haven’t materialized. In 2010, when NASA and the Western press declared the construction of the space station complete, they ignored the near-embryonic state of the Russian territory. The delay of the modules, which featured additional solar panels, communications gear, and life support and other systems, has created a growing dependence on NASA, and Roscosmos barters with them for electricity and whatever else its crew needs.

While answering online reader questions for the Moscow-based magazine Novosti Kosmonatiki, cosmonaut Sergei Ryazansky acknowledged the problem: “Our share in numbers [of scientific experiments] is obviously less than we wanted. We can argue about the scientific value of experiments conducted by our [non-Russian] colleagues, but their equipment and its deployment is thought out and organized much better. On Mir we had specialized scientific modules and the entire spectrum of scientific research, but the ISS, in this respect, is in much worse shape.”

Nor do Russian cosmonauts participate in non-Russian scientific programs. “Crews work together during the flight onboard Soyuz and during emergency practice drills,” Ryazansky explained. “The rest of the time, everybody works according to their plans and schedules. Of course, we try to get together for dinners, when we discuss current affairs, and to watch TV shows and movies, but unfortunately, not every day.”

Russian engineers have to rely on ingenuity to provide scientific and technological experiments on the cheap, or as they call it, na kolenke, meaning “on your lap.” In February 2006, a used spacesuit was repurposed to create a ham radio satellite. Engineers placed a radio transmitter inside the suit, mounted antennas on the helmet, and ran a cable through a sleeve to connect the various components. The cosmonauts then tossed the suit out during a spacewalk. When another suit was ready for disposal in 2011, they did it again. Another unorthodox science experiment involved testing reaction times in space by playing Tetris, a computer game as popular in the United States as it is in Russia, where it was invented.

A Day in the Life of a Cosmonaut

There may be no specialized labs on the Russian side, but what Zvezda does have is several portholes that make an excellent Earth-viewing station. Without much science to conduct, the cosmonauts have had time to produce an ever-growing catalog of photos from space. Crews on both sides head into Zvezda to snap landscapes, watch volcanic eruptions, and even observe rocket launches heading their way. Looking down at Mount Elbrus, a mountain in the Western Caucasus, cosmonaut Feodor Yurchikhin was so entranced that after he returned from orbit, he climbed the 18,000-foot peak.

With the view and not much else to do, the cosmonauts have tried to turn observation time into a practical activity. Oleg Novitsky has blogged about the enormous environmental damage resulting from oil exploration in the Caspian region—so pervasive it was visible from space. Cosmonauts have also reportedly caught tankers washing their toxic guts into the ocean, while one Russian promotional movie claimed that after the eruption of Iceland’s Eyjafjallajökull volcano, which paralyzed air travel in Europe in 2010, cosmonauts helped to establish the boundaries of the giant ash cloud. Russian crews have also tried to guide fishing vessels toward their catch and have reported plankton sightings to the Russian fishing ministry. Of course, satellites have long performed these kinds of observations, so making them from the space station is mostly a way to make the best of the cosmonauts’ time.

The Russians have had their stellar lookout post from the beginning—long before the U.S. cupola arrived. However, there is a glaring inadequacy in the views from both vantages, one that is felt more keenly by the Russians. When a student from Russia’s Yakutiya region—a territory bigger than Argentina—asked cosmonaut Aleksandr Misurkin to take photographs of the far eastern republic, Misurkin had to admit that he couldn’t see it because the space station’s path is too far south. In fact, cosmonauts can’t view the vast majority of Russia—the station’s orbital path is inclined 51.6 degrees from the equator, a compromise that allows station partners to send spacecraft to the station from their respective launch sites. Most of Russia is located at higher latitudes, and this geography is one of the leading motivators behind the decades-long crusade for the country to launch a future space station into a more appropriate high-latitude orbit.

One of the cosmonauts’ favorite activities—and one that brings them about as close to science as they’ve gotten—is growing plants. Going all the way back to the days of the Salyut and Mir space stations, in-orbit gardening was considered to be not just an experiment but an important way to raise the morale of cosmonauts packed for long periods in a tin can. (Those who have tried to care for a potted plant in a closet-size New York apartment will understand.)

During their stay in 2009, Maksim Suraev and Roman Romanenko managed to grow both wheat and salad greens. Despite a strict prohibition, they could not resist testing their space-grown produce. “Can you imagine,” Suraev wrote, “this green thing is growing out there, while two big cosmonauts just sit there and can’t touch it!” He confessed later on his blog, “In the end, we decided that no harm would come if we tried a little piece. We chewed on it and got really sad, because the grass turned out to be absolutely tasteless!”

But in Space Station Russia, even these low-budget experiments are intermittent at best. “Unfortunately, we are doing nothing at this point,” responded Feodor Yurchikhin to one of his blog followers in 2010. “The Americans prepare to launch a plant experiment on the U.S. segment, but it is quiet on our side…. We will come up with something new, I am sure.”

Just because they’re not doing much science doesn’t mean the cosmonauts are idle. They play a number of roles: movers, electricians, plumbers, and trash haulers. According to Sergei Ryazansky, Americans keep the U.S. segment in shape by replacing broken parts, but the Russian philosophy is to fix as much as possible. Almost every day some of the countless high-tech gear—on a space station, even the toilets are high-tech—requires a repair. Alarms go off frequently; even though most are false and an annoyance to the crew, the cause can take days to investigate. At one point, every time somebody approached the toilet on the Zvezda, a warning light went on.

A big part of the maintenance routine is cleaning and maintaining the life-support system on Zvezda. A special cooling and drying unit sucks in the station’s air to get rid of excessive humidity, and the crew needs to empty the system periodically with a manual pump. Sometimes, the dehumidifier is unable to cope, and the cosmonauts have to float around the station with towels to wipe off the metal panels. The unit that separates oxygen from water requires constant tinkering, as did the U.S.-built treadmill that was housed inside Zvezda, the only one aboard the station until the COLBERT treadmill was installed in the Tranquility node in 2009. The Russians finally got their own unit replaced in 2013.

Unbolt It, Unpack It, Don’t Lose It

Russia’s Progress cargo ships are fixtures on the station—at least one vehicle is always docked. It arrives as a supply ship, serves as a tugboat to move the station when needed, and leaves as a garbage truck, filled with station refuse, to burn up on reentry. When it arrives, the ship is usually stocked about half with Russian supplies and half with goods for the U.S. crew and other partners. According to Suraev: “We, unlike the Americans and Japanese, attach cargo seriously, like for a nuclear war. I can’t say why. G-loads are not really big at launch…and our partners long ago switched from bolts and frames to Velcro. On their side, it is one, two, and everything is out. But on our side, it looks like the systems we had [in the 1960s] are still there. In weightlessness, to unscrew a bolt that some big guy had tightened up on the ground is not that easy.”

Finding places on the station to store cargo has become an art in itself, involving the use of an elaborate tracking system. “I moved my slippers under the couch—database needs to be updated,” Suraev once joked. Russians look with some envy at the Americans, who rely on ground control to do most of the cataloging.

The Americans have always had been able to return cargo to Earth relatively easily on the space shuttle and now on SpaceX’s Dragon, which splashes down in the ocean for retrieval. But any heavy objects the cosmonauts bring to the station have to stay there or be sent to burn up with the Progress. Mass limits on the departing Soyuz vessels have been strictly enforced since a ship departing from Mir in 1994 collided with the station; the cause was traced to unauthorized cargo that shifted the capsule’s center of gravity. The only souvenirs Russian crews can bring home must be tiny enough to tuck under the seat on the cramped Soyuz spacecraft. When Ryazansky came home last year, he managed to squeeze in a decal of the Moscow State University, his alma mater.

Blind and Deaf

It’s not just the Western public that doesn’t see or hear much about the cosmonauts; Russia keeps its own citizens largely in the dark as well. Cosmonauts have had to defend the lack of transparency to bloggers who demand the Russian equivalent of NASA TV, which has broadcast live footage from the station continuously since construction of the U.S. side was completed. “Unfortunately, communications capabilities do not afford the deployment of video cameras in the [Zvezda] Service Module,” Oleg Kondratiev wrote in response to one of the queries, but, he assured the reader, “Even without video, the Russian cosmonauts are as busy with work as their American colleagues.” Technical issues aside, some cosmonauts are clearly not interested in living in a glass house. “Thanks, but [we] don’t need this,” Feodor Yurchikhin responded.

If Russian citizens ever get a line into the station, they might want to keep the sound off. The Russian segment is permeated with an ever-present buzz that, until recently, could reach as high as 67 decibels—a smidge quieter than a vacuum cleaner—according to Pavel Vinogradov, who spent two tours on board, in 2006 and, as commander, 2013. The main source of this nuisance: the ventilators, which work nonstop to force air circulation in the weightless environment. According to Oleg Kononeko, when it came to living in space, the noise was the most difficult thing to get used to. (Cosmonaut Anatoly Ivanishin tried to sleep with headphones, which succeeded only in suppressing the sound of his wakeup calls.) In 2013 new ventilators were finally installed that, well, “made our segment a bit quieter,” said Yurchikhin.

Lunchbox Trading

One big perk of international cooperation on the station is the advancement of the space food frontier. Astronauts and cosmonauts regularly gather on both sides of the station to share meals and barter food items. Roscosmos’ contribution to the food rations is the unique assortment of canned delicacies from traditional Russian cuisine. Perlovka (pearl barley porridge) and tushonka (meat stew), dishes familiar to the Russian military veterans since World War II, found new popularity among the residents of the station. Cosmonaut Aleksandr Samokutyaev says his American counterparts were big fans of Russian cottage cheese.

The cosmonauts, meanwhile, have few complaints about sharing meals with a country that flies up real frozen ice cream (not the freeze-dried stuff made for gift shops), as the U.S. did in 2012. Ryazansky has also spoken fondly of the great variety of American pastries. “We should say,” he clarified, “our food is better than the Americans’…. Despite the variety, everything is already spiced. But in ours, if you wish you can make it spicy; if you want, you can make it sour. American rations have great desserts and veggies; however, they lack fish. Our Russian food has great fish dishes.” The cosmonauts’ cuisine benefits when European and Japanese crew arrive. Both agencies brought unique flavors from their culinary heritages—including the one thing the cosmonauts really wanted. “Japanese rations have great fish,” Ryazansky wrote.

Every new cargo ship comes with fresh produce, filling the stale air on the station with the aroma of apples and oranges. Deprived of strong flavors in their packaged food, cosmonauts often craved the most traditional Russian condiment: fresh garlic. Mission control took the request seriously. “They sent us so much that even if you eat one for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, we still had plenty left to oil ourselves all over our bodies for a nice sleep,” Suraev joked on his blog.

Annexation on the Ground; Seccession in Orbit

In 2014, some Russian politicians, riding the swelling wave of nationalism following the Russian annexation of Crimea and angered by the U.S. condemnation, called for an end to Roscosmos’ cooperation with NASA. They suggested that Roscosmos detach the Russian segment from the space station as early as 2018. Roscosmos officials explained to hawkish politicians in the Kremlin that all of the key hardware needed to break off would not make it to the launchpad before 2020.

Roscosmos officials have said they intend to launch the egregiously delayed Multipurpose Laboratory Module by 2017 (10 years after the originally announced launch date), a node connector module in 2018, and a science and power module called NEM-1—which is still in early stages of development—by 2020. In that optimistic scenario, the Russian side would be completed just four years before the entire station is decommissioned in 2024. (Russia’s ultimate plan is to detach these last modules around 2024 and continue to operate them as a new space station.) By early this year, cooler heads in Moscow prevailed, and Roscosmos announced its intention to continue cooperation with NASA all the way to the station’s currently planned end. With the political unrest churning on the ground, the International Space Station remains one of the few areas where the U.S. and Russia can embrace a partnership.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AnatolyZak.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AnatolyZak.jpg)