The Recline of Civilization

The science of designing an airline passenger seat.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/76/4f/764fd260-596d-4534-b886-42ba322a049d/36f_jj2015_current175176_live.jpg)

If you have ever had the misfortune to occupy a temporary holding cell, you may not realize that you are inhabiting a set of state-mandated spatial requirements. These vary, but typically are meant to ensure inmates will spend no more than four hours in the facility, and that they will be accorded, roughly, 10 square feet of living space. In this way-station of the criminal justice system, the benches mounted to the walls typically afford no less than 24 linear inches in width per inmate.

Many more of us have experienced a different holding cell, a place where one’s living space maxes out at 3.7 square feet, where the linear seating width is a parsimonious 17 inches, where you may be prodded awake by a restless nearby inmate and, for reasons that are often poorly explained, housed longer than your appointed time. This is the holding cell of passenger aviation: the airline seat. It is part of a devil’s bargain, in which we relinquish comfort for the miracle of being whisked at great speed to almost anywhere on Earth, for a price that would have been unthinkable a few decades ago.

As someone who flies about 100,000 miles a year, I estimate I spend more than 200 hours—over a week—in airline seats. The majority of this is in Economy, what the industry calls “tourist class” seats.

But what was I sitting on? What thought (or lack thereof) had guided its creation? What market forces and federal regulations and design constraints shaped its contours?

I decided to find out.

Subtract and Divide

The place that produces the most economy class seats in the world is located in north Texas, a few hours up the road from Dallas. Zodiac Seats (previously Weber Air, before it was acquired by the French conglomerate) occupies a sprawling collection of low-slung factories and office buildings on the outskirts of the city of Gainesville. Robert Funk, the company’s vice president of sales and marketing, is a Pittsburgh native—despite Gainesville’s proximity to Dallas, his office walls are adorned with Steelers paraphernalia. Frequently when he meets people at parties, their first reaction upon learning what he does is to express surprise that manufacturing airline seats is an actual industry. “You mean they don’t just come with the plane?”

They do not.

“It’s like buying a house,” says Funk. “It comes empty.”

There are other constraints, like minimum aisle widths set by the Federal Aviation Administration. Seats must not touch the inner walls of the airplane. Designers have to account for a certain amount of flexing from the wall itself, as the aircraft sails through the atmosphere. Hence the tiny gap between the edge of the seat and the wall. “You have to think of the aircraft as a kind of long rubber balloon floating through the sky,” explains Tim Manson, design director at James Park Associates, a London firm specializing in transport interiors. “It will flex and move as it travels.”

And so the footprint of the seat, and the remaining “living space,” as Funk terms it, are essentially determined by one overriding piece of math: The available envelope of space that remains, divided by the number of seats the airline desires. Which is: as many as possible.

And airlines keep redefining what’s possible, so seats keep getting skinnier. While the rough industry standard on seat width “that everyone would like” is 18 inches, Funk says, today “we are building seats that are less than 17 inches wide.” On wide-body aircraft, he says, “you are seeing a push to narrow down the seats because you can get one more column of seats in.” The passenger’s “living space” largely stays the same over time because as design refinements create incremental gains in space, the airlines translate the added space into more seats per plane rather than more space per passenger.

As fuel costs rise, trimming weight has become the other driver in seat design. One of the heaviest items in an airline seat is the IFE, or in-flight entertainment screen. These have become crucial to the modern flying experience—“more expensive than the seats themselves,” Funk notes—and are so integral that providers like Panasonic and Thales have representatives on-site in Zodiac’s Gainesville factory to address technical issues as they come up.

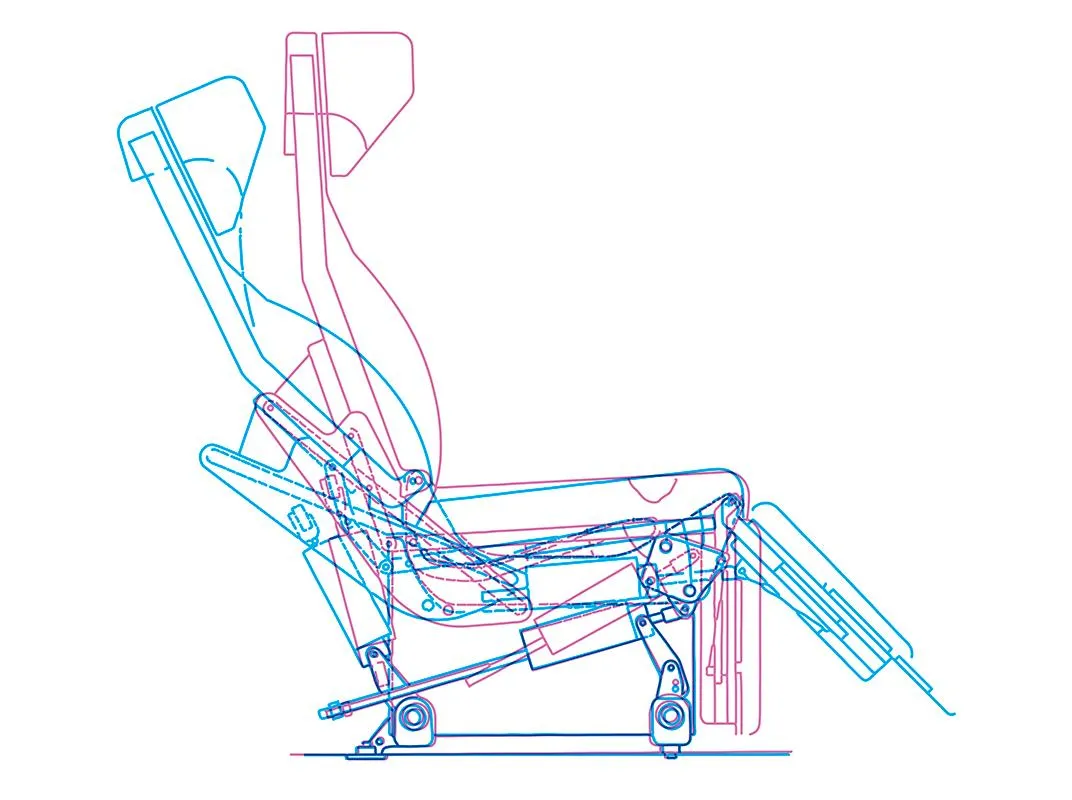

As technology develops and IFEs become lighter, changes ripple through the seat. On Zodiac’s factory floor—where it takes about three hours to assemble a complete seat—Funk shows me a machined aluminum “spreader” from the new version of the 5751, Zodiac’s most popular long-range seat, designed for twin-aisle aircraft and introduced in 2009. The spreader is the structural part of the seat, like a miniature bridge span located roughly at the passenger’s tailbone. As IFEs get lighter, the spreader has to absorb less load impact.

This has allowed the geometry to be changed, granting a touch more space for the knees of the passenger behind the seat. Many, including Funk, foresee the disappearance of IFEs themselves, in favor of passenger’s own mobile devices, a development he expects will allow the seats to grow thinner and lighter still, perhaps with some kind of provision for personal electronics.

If football is a game of inches, airline seat design is a game of centimeters. Much energy has gone into shifting to “upper literature pockets,” to give passengers’ knees a bit more clearance. Says Funk, “Some airlines don’t want an upper pocket because they want the magazine peeking out from the pocket below.”

But Klaus Steinmeyer, vice president of business development at Recaro, asserts that moving the pocket above the tray table is one of the specific design refinements of his company’s BL3530 Slimline model economy class seat that has improved passenger comfort. Another one Steinmeyer cites: The adoption of a slimmer backrest, filled with “netting material” rather than foam, that provides a modest uptick in legroom while still allowing airlines to reduce the seat’s pitch—the distance from one point of a seat to the same point on the seat ahead.

Seatbacks themselves have been shrinking over the years, another weight savings. The BL3530 Slimline seats sport backrests thinner than their armrests, and weigh in at just over 22 pounds apiece, backrest and cushion included, Steinmeyer says. Passengers gain a few precious centimeters of knee space, he asserts, without sacrificing back support. He says the ergonomic netting in the seatback of 3530 adjusts to the shape of the passenger’s body more fluidly than traditional foam seat cushions. He also cites the BL3530’s six-way adjustable headrest as an innovation that gives the passenger more living space—assuming, again, that the airline doesn’t cash in those modest, incremental space gains for another row of seats.

On the Zodiac 5751s I’m shown in the plant in Gainesville, I notice that a small arc has been carved out of the interior portion of the armrest—a minor detail that gives the passenger a minute amount of additional space, with an incremental reduction in weight. For the same reasons, armrests have become thinner on the bottom—just, as Funk says, “an arm cap.”

But this too is a trade-off. More substantial armrests provide more of a barrier; as passenger size increases in some markets, the “idea of somebody else touching you” underneath the arm rest could be off-putting, Funk says. As for the battle over armrest space, a Hong Kong product designer named James Lee and his company, Paperclip, have attracted much notice for a simple, elegant “double deck” armrest design, which allows neighboring passengers to claim different “levels.” So far, no airlines have installed it.

Luke Pearson is the co-founder and one of the two directors of PearsonLloyd, another London-based design firm. He developed Virgin Atlantic’s seats in Economy, Premium Economy, and Upper Class, which means he gets to ponder problems the people in coach can only dream about when they’re sitting bolt upright. A lot of thought (and development money) goes into premium class seating.

“There are only so many ways you can configure humans next to each other when they’re lying down,” Pearson says. “Shoulder space varies a lot and foot space little, apart from length. This is why it makes sense to overlap shoulders with feet when possible.”

Benjamin Saada,CEO of the French firm Expliseat, says he was motivated to found his firm with two other entrepreneurs in 2011 when he realized, over many flights, that nearly all the improvements in the air travel experience have gone to the minority of passengers who can afford to pay a premium. “All of the innovation was just for Business and First Class,” Saada says. “But Economy class is where most of the passengers sit.”

Saada claims Expliseat’s Titanium Seat is, at four kilograms (nine pounds), the world’s lightest Economy seat. Its thinness translates to an additional five centimeters of passenger legroom, Saada says. So far, it has sold to two airlines, Air Mediterranean and the Congolese carrier CAA; Saada expects to announce additional buyers at the Paris Air Show.

His other boast sounds almost too good to be true: The Titanium Seat’s carbon-fiber frame is so impact-absorbent you won’t feel it when the passenger behind you kicks your seat or knocks his tray-table around. Saada hopes the airlines who buy his seats will emphasize this perk.

“It’s become a key selling point [for airlines] to talk about the seats in the cabin,” Saada says. He also says that when an aircraft carries lighter seats, it uses less fuel, reducing the plane’s carbon footprint.

What becomes clear, as I walk the floor at Zodiac, looking at skeletal frames awaiting textile coverings, or rows of shrink-wrapped finished seats, is how far from a simple piece of furniture an airline seat is. For one, it is more than a seat. That 3.7 square feet is not just living space but also a work area, dining area, theater, even a sort of bed. Something as basic as a cushion is also, as the public address announcements remind us, a “flotation device.” Lurking underneath the cushion is the power supply and hardware for the IFE, encased in a shroud meant to protect it from the inevitable spills of soft drinks down the seat cushions.

While the passenger may hardly think of it, airline seats are also part of the work environments for flight crew, particularly in premium classes. “We often think of passengers as the users,” says James Park Associates’ Manson. “But the cabin crew use the product day in and day out, just handling it and touching it. They’re going to have to retrieve that passport that’s gone down the side.” Even in economy there are discreet signs of this: Funk points to a seat for an Asian carrier; almost hidden on the side is a small footstep to help the airline’s statistically shorter attendants reach the overhead compartments.

The design feature passengers know least about is the one they hope they’ll never need: their performance during a crash. During our tour, Funk and I come across a just-concluded “head path” trial on Zodiac’s test sled. In a twin set of Zodiac seats, a pair of mannequins lie slumped over, each of their heads bearing what the test engineer jokingly calls a “Mohawk”—a piece of paper with a graphic icon. During video analysis, the engineers can tell how far forward the passenger’s head moved, and if it would have struck a bulkhead, without the company actually having to build a bulkhead.

The sled moves only 30 mph down the track, but it stops in less than foot. “It’s going to be pretty violent,” Funk says. Everything is tested for its performance in these extreme scenarios, from whether the luggage bars underneath the seats can restrain a laptop speeding forward to how a passenger’s shins hit the lower seat “tubes”—that is, the structural beams in the frame below the “seat pan,” the part you sit on, at its front and aft edges.

As the trade publication Airline Passenger Experience observed, the July 2013 crash of an Asiana Airlines 777 in San Francisco was both a testament to the benefit of 16-G crash-tested seat design (in terms of passenger survival) and a reminder of how much safety engineering is still needed, given the number of passengers who sustained spinal cord injuries.

Things like three-point safety harnesses, already standard for crew and in some premium sections, often come up for discussion, says Funk. As with every change, designers must balance the calculus of cost, complexity, and compliance.

When passengers look in vain for power outlets in their row, they are coming up against an inexorable business cycle: Personal electronics change far more rapidly than airline seats are replaced, usually no more than once per decade. “We have seats that have been flying [for] 25 years,” Funk notes.

At least one pricey misstep a generation ago has made airlines more risk-averse: They installed, at great cost, seat-back telephones as a passenger convenience (and source of revenue). But passengers tended not to use them, even before cell phones were widely adopted. “The general public tends to forget that the fare they pay funds all this,” Funk notes, gesturing at the broad expanse of seats-in-progress. “I’ll put a water fountain on the seats if they’ll pay for it.”

But what about the seats themselves? Why are they so uncomfortable? Or are they? Comfort can be a surprisingly slippery thing to nail down.

“Despite the frequent use of the term comfort,” notes a study in the journal Product Experience, “there is no such thing as a general notion of comfort or discomfort.” As a man whose height is roughly in the 95th percentile, my view of what is comfortable may be different, Funk points out, from that of a 10th-percentile-height woman who doesn’t want “her legs to dangle.”

In an email, Recaro’s Steinmeyer asserts that his company’s CL3710 seat has a “six-way adjustable” headrest making it “ideal for children, small persons, and seniors.”

It probably won’t do me much good.

Pleasure and Pan

Backward-facing, or “angled,” seats in premium classes are de riguer at some airlines, verboten at others. Passengers’ perceptions of comfort may heavily be heavily influenced by everything from ambient temperature to the demeanor of the flight attendants to whether they were able to binge-watch season 3 of “Breaking Bad.” “Removal of sources of discomfort will only ever result in a neutral perception of overall comfort,” Ben Orson, James Park Associates’ managing director, writes in an email. “To create a memorable sense of comfort,” airlines must offer not just the absence of pain but at least a little pampering: He cites the turn-down service some airlines offer for passengers wanting to sleep.

Discomfort is subjective, too. One person may be annoyed by the seat pitch; another by its width; for another, the headrest could be the source of pain.

Then there is time. “A cushion is different after a half-hour than after five hours,” Orson points out. Seats made for long-haul flights offer more recline and calf supports to spread the load to the passenger’s back and legs.

Moreover, “comfort” can be counterintuitive. When I suggest to Funk that people might like economy seats to recline a bit more, he notes that what matters is less the absolute distance a seat tilts back than the angle of recline. “When you get beyond six inches, it’s actually uncomfortable,” he says. You push more weight onto your bottom as you slide forward.

These sorts of lessons have been learned at Zodiac’s ergonomics lab, a small room featuring a modular, full-scale airline cabin mock-up in which test subjects, dressed in business attire (which they get to take home), spend six hours and upward in test “flights”—with a drinks service and all. Subjects, wired with electrodes, are monitored for signs of discomfort (e.g., tensed muscles). A nearby tub is used to help measure the swelling associated with deep vein thrombosis. Before and after their “flight,” a subject sticks his or her foot in the tub, and the level of fluid displacement reveals if the foot has taken on more blood.

Lab results have affected seat design. When the Zodiac 5751 reclines, notes Funk, the seat pan actually pivots upward. In one section of the floor of the Zodiac ergonomics lab is an Air New Zealand “Skycouch,” a three-seat unit. Presuming one has booked the three seats across, one can touch a button to extend the seats’ footrests; the three seats and the three footrests are then fused into a lie-flat “bed.” In another corner, I am shown a new “zero-gravity” Zodiac business-class seat, soon to be introduced by American Airlines, which can lie flat but also features a La-Z-Boy-style recline option that elevates the passengers’ feet above their hearts, allowing the overworked veins in their legs to rest, reducing swelling and improving circulation. “It actually tests more comfortable that way,” Funk says.

More radical scenarios—like “capsule hotel” style vertical pods—haunt prototype labs and patent offices. But that seems a stretch when more humble innovations, like Paperclip’s armrest, struggle for acceptance.

Pearson says passengers are attuned to what sorts of creature comforts they can expect at what price. “Opportunities for defining a different proposition and getting it right are small and high-risk,” he says. Thus, “unless the proposition is significantly better, price rules.”

Later that evening, with storms along the Eastern Seaboard beginning to disrupt flights, I scramble for a standby seat on an earlier flight. I am given, thanks to the good graces of a United agent and my elite status, the last seat, 32C. With my knees pressed up into the reclining seatback in front of me and my own non-reclining seat wedged against the noisome lavatory wall, I am acutely aware of my place on the edge of ergonomics for the 95th percentile male. Uncomfortable as I am, I am glad to be going home.