Remembering the Iconic Airport Diner

Reflections in a greasy spoon.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0a/1b/0a1bf6af-c84f-4949-91bb-6aef8ba442cf/17b_sep2017_scan030_live.jpg)

Anyone growing up in New Jersey appreciates a good diner and loathes an impostor.

A diner needs to be in a building all its own; it can’t be in a mall or part of a chain. There should be chrome and neon. The owner must be the cook, or at least used to be.

It can be a man or woman behind the counter sliding eggs off the griddle with a metal blade and onto oval ceramic plates chipped on the edges. No plastic forks, no Styrofoam cups. Ceramic and stainless steel, or don’t call it a diner. Look for a grease-speckled health department permit yellowing on the wall beside the grill, just above the cook’s ashtray, or—depending on local law—where the ashtray once sat. The food must be simple: eggs, any style, any time of day; hash browns made fresh every morning with onions and warming on the griddle; coffee, free refills and always fresh, even if it’s yesterday’s (don’t ask for tea); burgers, fries, ketchup. If you spot squeeze packets, just walk away. That ain’t no diner.

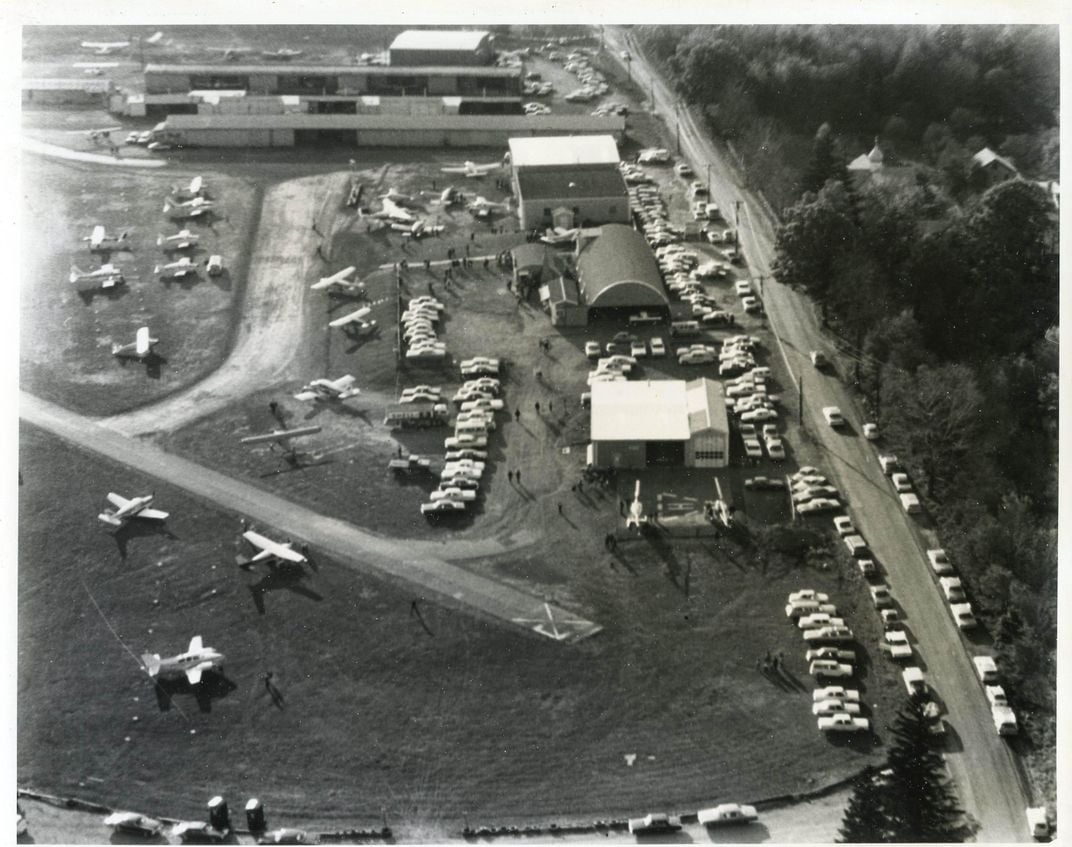

The best diners are at small airports. Or were at one time. My favorite was at Ramapo Valley Airport in Spring Valley, New York, just across the border from where I grew up in northern New Jersey. In the early 1960s my father would take me to Ramapo when there were too many Sunday visitors in the house. “Hey, let’s go to the airport,” he’d say, and we’d climb into the ’56 Plymouth wagon.

There were two small airports equidistant from our house: Teterboro was the big industrial airport, with rows of single- and twin-engine airplanes, flight schools—first lesson $5—a control tower, and large maintenance hangars, one of which housed whatever airplane Arthur Godfrey was flying back then. I saw, and heard, my first Learjet at Teterboro; painfully noisy on takeoff, but I didn’t dare cover my ears, didn’t want to be the wimp on the ramp. Didn’t affect my hearing either. I just wish kids nowadays would speak up.

Teterboro had a cafeteria. The small airport had a diner, which was, technically, not a diner. It was more of a coffee shop. A counter, a few stools, and maybe three tables, where pilots would spread sectional charts, stained with burger grease. They’d draw lines with number 2 pencils and say things like, “ground speed,” and “Watch the crosswind over the runway threshold.”

They were my heroes. Mostly men but not all, they walked the same planet as I but possessed the magic to leave it at will. They swaggered. They stood tall. They smoked Luckies and drove stick-shift cars getting 10 miles to the leaded gallon.

I remember one pilot casually mentioning that he’d been to Vermont that day. Vermont! In one day. I’d never been farther north than the Catskills and that took a long time by car. To be able to eat breakfast at the Ramapo Airport diner, climb into a Ryan Navion, and fly to New England and back in the same day just squeezed my brain.

There were no pilots in my family. No airplanes. No dreams above the second floor. My father had served in the Army Air Forces in World War II as an enlisted man in the 442nd Troop Carrier Group. He’d flown in C-47s but never as pilot. His dream never came true, but he made certain to show me where the airport was and how to behave there. Never climb on an airplane uninvited. Watch for propellers; you get bit by one and it’s your fault, should’ve been watching. Stay off the runway. If someone offers you an airplane ride—unlike if a stranger offers you a car ride—take it.

My father stopped taking me to the airport when I was about 12, so I’d pedal the eight miles there, mostly uphill; took about an hour. Return trip was all downhill, easy, and home for supper, where no one asked, “Did you hang around Ramapo Airport today?” They didn’t offer. It was my place now. Few of my friends ever accompanied me—they didn’t see the point. “What do you do here?” they’d say. I couldn’t explain, and if they accompanied me once, they’d never return. Probably still attached to the earth. Their loss.

And always there was the airport diner. I usually didn’t have enough money to buy anything, but on warm days I’d sit outside and listen to the pilots—many who didn’t actually fly—relive every hour of their airborne lives.

A low fence separated the diner’s parking area from the flightline, beyond which only pilots could wander. Or so I thought, until I realized that fences are an illusion. They can’t keep anything in or out if it’s determined to get through. When I first rode my bicycle alone to Ramapo airport, I discovered that if you ignore the outward trappings of authority, the world on the other side of any fence that relentlessly beckons becomes accessible.

Once I realized that I could wander almost anywhere on the airport provided I didn’t do anything dumb, I found an environment that made sense to me—not easy for any teenager. Rows of hangars, each protecting something with wings capable of going anywhere, and each holding the physical being of past adventures in the sky.

The Quonset hut hangar behind the diner housed a biplane; a Beech Staggerwing, I heard someone say, when they didn’t know I was hiding in the shadows, afraid to come out and be unmasked as the trespasser I was. And there was a flight school with Piper Cubs, Tri-Pacers, and the ultra-modern Cherokees. My imagination always saw me in the yellow Cubs. Still does.

I took only a few airplane rides from Ramapo Airport in the 1960s, and returned once after the Army. I was a pilot by then. I rented a Cessna 172 only to make one of the worst landings possible without triggering NTSB attention, but at least I’d flown from my childhood dream field.

Afterward I took a seat inside the Ramapo Valley Airport diner and ordered coffee, which I normally never drank. I wasn’t a smoker, but if someone had offered me a Lucky Strike, I’d have lit up, blown rings at the ceiling fan, and held forth on the tricky crosswind over the threshold.

But I sat alone and felt the airport slip away. A week later, I moved west, and 10 years after that Ramapo Valley Airport died beneath suburban sprawl. It was inevitable. The diner, which had morphed into a tavern, is gone, as are the airplanes, hangars, and pilots.

But all those flying stories launched over coffee and apple pie? They’re out there, floating in the wind, intermingled with memories of eggs and hash browns, cigarette smoke, and leaded avgas fumes—all still flying inside my head and always in search of a place to land near a real diner.