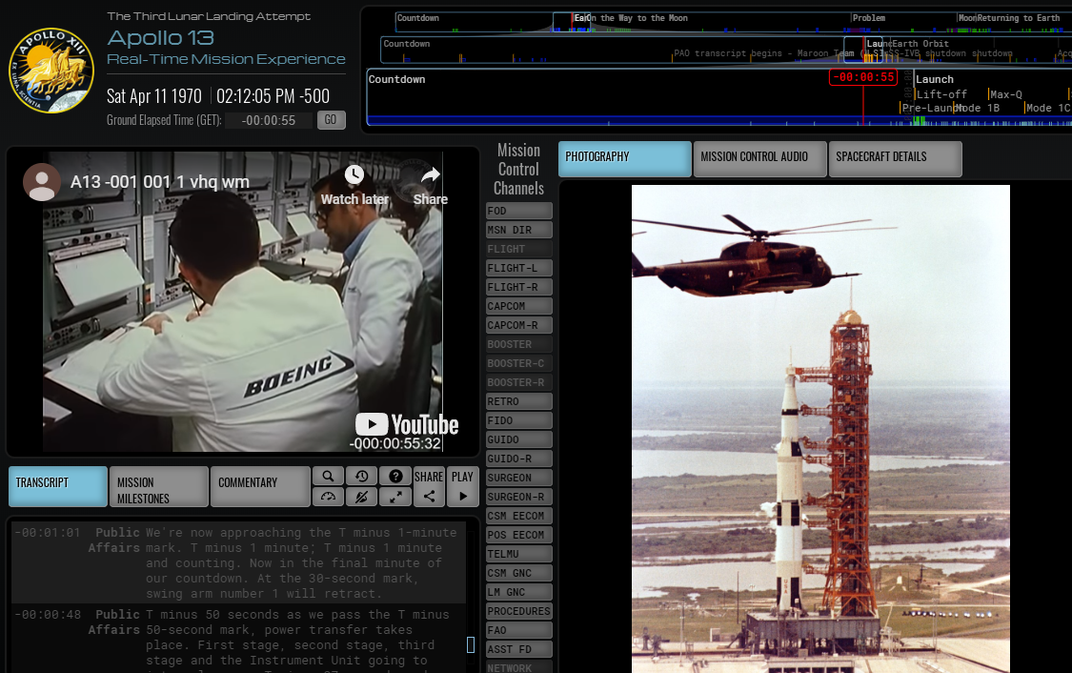

Relive the Drama of Apollo 13 in Real Time, As It Happened

A new multimedia site creates the historic mission 50 years later.

:focal(886x1141:887x1142)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/b7/49b760a7-f65f-4c47-93e8-838f4aa50e40/9038_crop.jpg)

Fifty years ago next week, NASA came close to losing one of its Apollo lunar missions. The story has been told many times, notably by Ron Howard in his 1995 film Apollo 13, which (mostly) faithfully recounted the story’s main elements: the explosion on the way to the moon, the stoic endurance of the astronaut crew, and the ingenuity of NASA engineers who devised a way for Jim Lovell, Fred Haise, and Jack Swigert to use their lunar module as a lifeboat to make it back to Earth.

What’s missing from the previous books and documentaries is the fantastic complexity of that week-long rescue operation. Missing until now, that is. Last month the Apollo 13 in Real Time site went live—an unprecedented multimedia collection of thousands of hours of audio and video, transcripts, and hundreds of photographs, all synchronized and running continuously to recreate the Apollo 13 flight as it happened, from start to finish. You can tune in from the beginning or pick up at a particular point in the mission.

This monumental work—one of the most ambitious multimedia history sites ever created—was the brainchild of Ben Feist, who started out as an amateur Apollo historian but so impressed NASA with his Apollo 17 and Apollo 11 real-time sites that the agency hired him to build sites for more missions. Feist spoke to Air & Space Senior Editor Tony Reichhardt in March, a couple of weeks before the site went live in anticipation of the 50th anniversary of the launch on April 11.

Air & Space: So this is the third Apollo mission site you’ve created from all that recorded audio and video. Given what happened on Apollo 13, are you seeing a different tone to the conversations in Mission Control, where you can tell there’s a tenser atmosphere?

Feist: Yeah. Most definitely. And we were a little bit fearful, “What if everybody lost their cool? We’re going to be undoing the reputation of NASA by releasing this material.”

But I’m relieved to say that everybody was super pro, and just went into full-on hard work mode. If you listen to enough of this material, you can tell certainly by the speed they’re working that they’re not losing their temper with each other. They’re just going super fast and working the problem, especially right after the explosion. There’s a famous shift when [Flight Director] Glynn Lunney and his team took over right after the explosion occurred, about an hour later. Stories have been written about what Lunney did on that shift, and he is just unbelievable. He is thinking faster and pushing people harder than I think I’ve ever heard anybody do in Mission Control. You’ve heard so much about the history, but to actually hear it occurring is amazing.

Nobody is being short with each other or yelling “Wait a minute!” if someone asks for something?

No, if they need a minute, they say, “Give me a minute.” And the other guy says, “Okay.” But later, when everybody is a little more relaxed, there are a couple of moments where they’re talking like, “Don’t argue with me. I’m not asking you. I’m telling you. Don’t argue with me.” That kind of stuff. But it’s not ever done with a short temper or anything.

[Apollo 13] really feels a lot different than the other missions, especially because all the outgoing phone calls from Mission Control were recorded, because they used the headsets and they had a phone on the console. So they’ll phone home and say, “I’m not coming home because there was just an explosion on board.” That’s when they let their hair down a little bit, and they’re no longer a flight controller. They’re just a person talking to somebody else who asks, “Oh, really? Are they going to be okay?” “Well, it looks like they’re going to be okay, but I’m sorry, I can’t talk right now. I got to go.” And you’re like, “Did that phone call just happen?”

There’s even a call with [Apollo 13 commander Jim Lovell’s wife] Marilyn Lovell the morning after the explosion, and she hasn’t slept all night. It’s just amazing to hear this stuff.

There are things we’ve learned from listening, like apparently [the controllers] would all go down to the booster console [in the Mission Control room] and use that phone, because it was away from everybody else in the front left corner. And [the booster systems engineer] doesn’t do anything after the launch. It was sort of a vacant spot. I was like, “Why are the boosters always on the phone?” Then I realized, “Oh, this is just where people went. This is why [astronaut] Gene Cernan’s on the phone there all the time.”

We’ve actually got one of our team members writing a piece of software to scan through these audio files and look for phone calls because the dialing has a certain audio fingerprint.

What were you doing before you created the first site for Apollo 17?

Feist: I worked for 22 years in the advertising industry, on the digital side, building commercial websites. And I did the Apollo 17 stuff in the evenings, just for fun, to unwind after work, like reading a book or something.

You were just doing it for yourself?

Right. There were some people in the space history world, like David Woods who runs the Apollo Flight Journal, who I had reached out to. And I started blogging about what I was doing, because I was afraid someone else out there might be doing it too. And what a horrible waste of time that would be.

You must have been well into it when NASA released that mountain of raw audio from all the communication channels in Mission Control.

Yeah, 2012 or 2011 or so, I think they began releasing that stuff. And that’s really two guys at Johnson Space Center who I know quite well now, Greg Wiseman and John Stoll. Just as I was trying to reconstruct the transcripts for Apollo 17, this audio appeared online and I thought, “Oh my God, this project just got a lot bigger.” It meant…laying in that audio, and stretching it and tweaking it and cutting it and making it fit an actual digital timeline.

Did the film all exist in one place or did you have to go to different sources for that?

No, the film definitely did not exist all in one place. I was approached by a gentleman named Stephen Slater from the U.K., who’s become a longtime collaborator with me now. He was actually archive producer on the Apollo 11 film last year.

Stephen is a collector who provides to the film industry NASA material. So he had everything, and I think he reached out to me because he saw that I had probably everything too. Our conversation basically started out as, “Do you have this or that?” And then eventually it turned out, by the end of the project, he had provided me pretty much everything. All the television transmission footage and 16mm film and Mission Control film and things like that.

As for audio, on Apollo 17 you only had the onboard voice and the air-to-ground, but for Apollo 11, you had all these channels of conversation in Mission Control. And I gather there are a lot of them?

Yes, there are 60 tracks. Two 30-track recorders. Then, if you take out the Department of Defense channels that were redacted, and some other unused time-code tracks, it’s about 50 channels of conversation.

Wow, and how hard was that to sort out who was talking and when?

Way more difficult than any other part of this entire endeavor. There’s one machine remaining that can play these tapes, in Houston, and it was broken. The tapes themselves were [at the National Archives] in College Park, [Maryland] so the National Archives can’t play them back and neither can [NASA] Houston. Very long story short, I think it was almost five years of work. The University of Texas at Dallas got a National Science Foundation grant, went through all the process of restoring the machine and getting a new play head that could play all 30 channels at once.

What arrived in my hands was a hard drive full of thousands of hours of audio that was just in the worst shape you can imagine. It was full of speed variations, way worse than the quarter inch stuff that was done for Apollo 17.

Some of these conversations are “back room” people talking to the mission controllers out front, right?

Yup.

Was it easy to figure out who was talking to whom, or did you have to puzzle that out?

No. We don’t know [the names] of any of the people. I mean, there’s a list of people who were working on each shift. But we haven’t created a transcript of who this person is who’s speaking and what did he say. It’s just, tune in to the EECOM [Environmental Control and Life Support] loop, and you get to hear what the EECOM [flight controller] heard and said. There’s no explanation anywhere of what they’re saying. That’s up to the public to figure out. The material’s been made available, but nobody has listened to it all. I certainly haven’t listened to it all.

This almost omniscient view of the mission is something that probably didn’t exist at the time, even for someone like Apollo Flight Director Gene Kranz. Was there any one person who experienced Apollo 13 the way somebody can today on your site?

No. Certainly not. Actually, for Apollo 13, these tapes were used in the accident investigation. That’s kind of what their purpose was, like an audit. [They could] go back and see if there were any mistakes made that may have led to whatever happened on Apollo 13. There’s no information in the report about precisely what they did with the tapes. But we know they were kept with the investigative material at the National Archives.

Tell me some other other insights you’ve had from listening to the Apollo 13 conversations.

Well, there’s lots of information to be gleaned on when did things occur and how fast did they develop on the ground. There’s a lot of historical inaccuracy to undo after the Apollo 13 film. That is a good Hollywood film that captures the essence. But the [film] details that people now remember as fact, you realize what kind of damage something like that can do for history. In the film it’s depicted like [the astronauts] know what’s going on onboard, and the guys on the ground are kind of playing catch-up until eventually the guys on the ground crack the case.

But they knew on the ground that there was a problem before the radio call came down [from the astronauts] to say they had a problem. They were talking about it already, like, “What’s going on? What just happened? What’s wrong with your data?” one guy yells in the background. And Sy Liebergot, who was [the EECOM] on shift, did an amazing job in keeping his cool and just working immediately.

The film is like any dramatization, but the reality is a lot blurrier than that, and to hear it happening is different than somebody’s interpretation of what’s happened. That’s what I really like about this depiction of history. It takes away everybody’s “stories over drinks” from the last 50 years, and the rose-colored lens we use to look at the past, the feeling that back then they had the right stuff, and everybody was special in some way, and now we aren’t. This is like, “No, no, no. They were the same as us. Listen to this. They’re complaining about working overtime during Apollo 13. That’s not the right stuff.” But actually, yes it is. They got the Presidential Medal of Freedom for that mission, and rightly so. But they were just people, they were human.

Do you know if anyone has used your site to listen to a mission from start to finish?

I heard from one guy who did.

Really?

One guy changed his sleep cycle to match the crew. And woke up every day and listened through. I was like, “Wow, that’s a whole other.... I thought I was crazy.”

For Apollo 13, we’re launching a forum to go along with the site. It will be a place where you can share links to moments that you find. You can establish a link and it’ll jump to that moment in a given channel. You can say, “Hey, check out this phone call, and here’s a link to it.” The forum will be a place to share and discuss, and hopefully get some crowdsourcing done on 7,200 hours of audio that nobody has listened to. You might be the first person to hear it, and it might be important.