Replicating Reims

A virtual race to mark the 100th anniversary of the world’s first air meet

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Reims-flash.jpg)

In the summer of 1909, the aviation world was spoiling for a fight, or at least a contest. There were too many airmen on both sides of the Atlantic laying claim to the title of World’s Greatest Aviator. So on August 22, at a racetrack outside Reims, France, they met for a week of competitive flying, with prizes awarded for speed, altitude, and distance flown. It was the world’s first large-scale air meet.

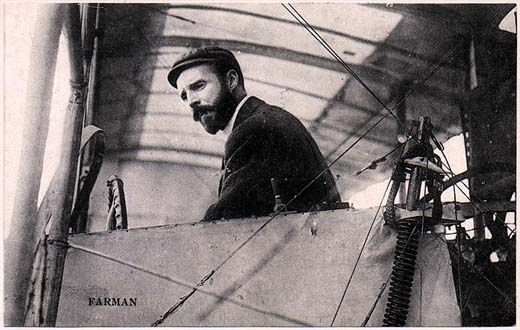

Most of the 22 pilots were French, including Hubert Latham, Henri Farman, and Louis Blériot, who a month earlier had won international admiration for crossing the English Channel by air. The Wright brothers were notably absent, but American Glenn Curtiss took home the prize for speed, completing two circuits of the 6.2-mile course in 15 minutes and 50 seconds, for an average of 46.5 miles per hour. As many as 500,000 spectators attended the meet, firmly establishing air shows as a viable and popular form of entertainment.

Fast forward a century, to a flight simulator at the University of Liverpool in England that looks more like a space capsule than something from the age of wooden airplanes. On August 26, to mark the 100th anniversary of the Reims air meet, teams of pilot/ engineers will take their seats inside the simulator to “race” virtual recreations of several of the aircraft that flew at Reims. (See the videos at right)

Mark White, who manages the university’s Flight Simulation Laboratory, is quick to say “These aren’t exact simulations, they’re approximations.” But the engineers have taken pains to use real data on the size, weight, and geometry of several 1909 aircraft, including the Blériot XI, the Wright Model A (flown at Reims by Eugene Lefebvre), Farman and Voisin biplanes, the Antoinette monoplane, and Curtiss’s Reims Racer. Using a simulation program called FlightLab, they’ve created virtual airplanes with aerodynamic characteristics very close to those of the originals. When the virtual aircraft fly the simulated course, “We may be off by a few seconds [from the actual times recorded in 1909],” says White, but they reflect the true performance of the racers at Reims.

One by one, the virtual pilots (some of whom are real-world pilots of vintage aircraft) will record their times around the course, while sitting at controls inside the lab’s Heliflight-R motion-based simulator, which reproduces the feel of flying a 1909 racer (though not the look—a simple control stick replaces the original wooden steering mechanism). Then, toward the end of the day, they’ll race head-to-head in two simulators. For the engineers at Liverpool, it’s a way to have a bit of fun while showing off their ability to faithfully model the handling characteristics of vintage airplanes.

What they won’t likely be able to reproduce is the stunned silence of the Reims crowd on August 28, 1909, when Blériot, the favorite and the last to race, failed to beat Curtiss’s time. “Great was my surprise…when there was no outburst of cheers from the great crowd,” Curtiss later recalled. “I had expected a scene of wild enthusiasm, but there was nothing of the sort. I sat…a short distance from the judges’ stand, wondering why there was no shouting, when I was startled by a shout of joy from my friend, Mr. Bishop, who had gone over to the judges’ stand.

“ ‘You win! You win!’ he cried, all excitement as he ran toward the automobile. ‘Blériot is beaten by six seconds!’

“A few minutes later, just at half past five o’clock, the Stars and Stripes were slowly hoisted to the top of the flagpole and we stood uncovered while the flag went up. There was scarcely a response from the crowded grand stands; no true Frenchman had the heart to cheer.”