Restoration: Beech Staggerwing

A true story with an O.Henry ending.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Arch_D17S_Rest_Main_AM09.jpg)

Lloyd Cizek points at his chest. "I had a little electrical problem, so they had to install an auxiliary power unit," he says, joking about his cardiac pacemaker. Cizek retired as a Northwest Airlines 747 captain in 1990, and since then has been in an on-again, off-again battle with the Federal Aviation Administration over his pilot's medical certificate. Now the only way he can get it back is to run nine minutes on a treadmill while hooked up to a heart monitor. "I just can't do that," he says.

Behind Cizek, in his hangar in Amery, Wisconsin, sits his 1940 Beechcraft D17S Staggerwing, serial number 398, which he has owned since 1979. Its nine-cylinder, 450-horsepower Pratt & Whitney Wasp Junior radial engine slowly leaks oil into a drip pan on the floor.

Cizek calls his Staggerwing Lais, after the fourth century B.C. courtesan from the Greek city-state Corinth. A plaque inside the door notes that she was "known for her beauty and fine lines and also had a reputation for being somewhat fast." "Can you think of a better name for a

Staggerwing?" Cizek says with a grin.

The aircraft type was called Staggerwing because its top wing is set slightly aft of the bottom one. Aimed at the corporate market, it debuted in 1932 for $14,000 and up. During the aircraft's 15-year production run, Beechcraft built 785.

Construction was largely spruce and fabric; interiors offered leather, mohair, and mahogany. The 200-mph biplane also served as a racer, a bomber for Republican forces during the Spanish Civil War, and a VIP transport for the U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II. The Army and the Navy bought 260 and commandeered as many as they could find from private owners. Such was the case with Cizek's airplane, which flew courier duty for the Navy along the U.S. East Coast and later was sold as surplus.

Today, the 200 or so Staggerwings that remain are regarded as flying works of art. A rare G model in mint condition can fetch perhaps $525,000.

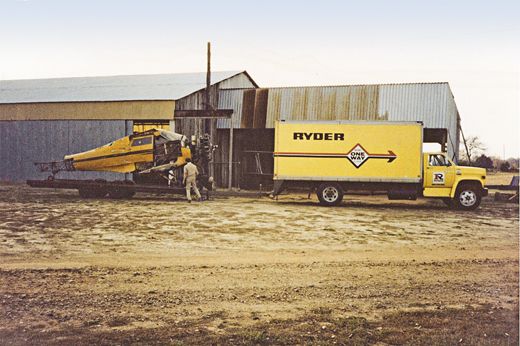

Cizek became enamored with Staggerwings as a boy when he saw a model in a hobby shop. In 1979, he read an ad for one in Trade-A-Plane and called the seller, Tom Todd, a cotton broker and World War II PBY pilot. Todd explained that the airplane "was a basket case," in pieces in a barn on his Mississippi farm. Undeterred, Cizek lashed the Staggerwing's remains to a borrowed trailer and headed home.

Cizek spent the next 18 years learning woodworking, metal forming, and wiring and obtaining an airframe-and-powerplant mechanic's license and an aircraft inspector's license. He stripped the airplane to the frame, replaced the engine with a rebuilt one, and upgraded the electrical system from the original 12-volt to a modern 28-volt so the airplane could carry modern radios, GPS technology, and autopilot. However, the replacement avionics and radios were narrow and long, while the originals were wide and short. Cizek made 10 instrument panels until he got it right.

Employing a borrowed English Wheel, a device for forming flat sheets of metal into compound curves, Cizek fashioned a more aerodynamic cowling. He modified the retractable landing gear to make it more reliable, upgraded the brakes, and changed the tail-wheel setup to make the airplane easier to tow. He installed modern fuel valves and fuel monitoring systems, gutted and re-covered the interior, and designed and installed an all-metal firewall—"The old one was fabric," he says incredulously.

Finally, in 1997, Cizek ran out of things to change or fix and the FAA signed off on his work. "They gave me an 'A' for airplane and an 'F' for paperwork," Cizek jokes. However, by then Cizek's medical issues had squelched his opportunity to fly. "When I could fly, the airplane couldn't, and vice versa," he says. Over the last decade, Cizek has flown the Staggerwing only 12 hours. But he's not bitter. "It was a lot of fun. I got more joy out of solving the problems and making things," he says. "Everyone has to stop flying sometime."

He pulls on the cowling and notices water leaking out, leftover rain the Staggerwing encountered on the way home from the Experimental Aircraft Association annual fly-in at Oshkosh, Wisconsin, just a few days earlier. Cizek's friends flew the airplane there, parked it in the vintage aircraft section, and threw a "for sale" sign on the propeller. Asking price: $375,000. There were no takers. As Cizek tells me this, I get the feeling that he is not entirely disappointed.

Mark Huber has written about the old, the odd, and the obtuse for Air & Space since 2000.