Restoration: Connecticut’s State Warbird

What World War II fighter was a product of the Nutmeg State?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Resto_Flash_History_FM10.jpg)

In 2005, the Connecticut legislature unanimously declared the Chance Vought F4U Corsair, the renowned World War II fighter with an inverted gull wing, its Official State Aircraft.

“It was a no-brainer,” says Craig McBurney, a driving force behind the effort. “It’s the only aircraft designed and built in one state by one major corporation in World War II,” he says of United Aircraft, the parent company of the manufacturers that built the airframe, engine, and propeller. The Corsair would have needed long, and thereby heavy, landing gear to give the massive 13-plus-foot propeller ground clearance. So engineers canted the wings, allowing for shorter, lighter landing gear at each wing’s low point. The F4U started life with the 2,000-plus-horsepower Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp radial, which, at the time it was introduced, was the most powerful fighter engine.

Of more than 12,500 Corsairs built, fewer than 20 are flying today. “Even most people who don’t know airplanes know the airplane,” says McBurney.

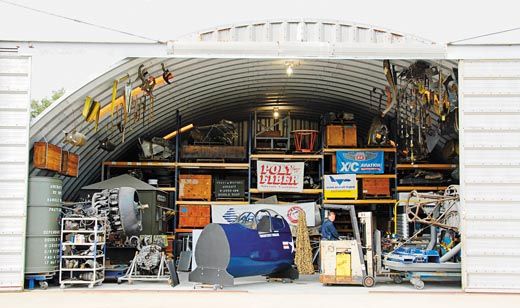

He’s speaking inside a World War II-type Quonset hut he re-created out of a hangar at Connecticut’s Chester Airport, headquarters for Connecticut Corsair, the organization he founded to restore a wrecked F4U-4 he bought in 1993, registration number N5222V (originally Bureau Number 97330). The scarred mid-section of the fuselage is the largest piece. A canopy, wing ribs, and other parts hang from the ceiling. Others lie in crates stacked on shelves that reach the roof.

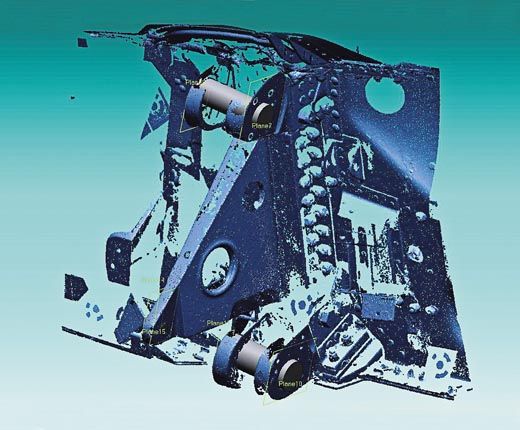

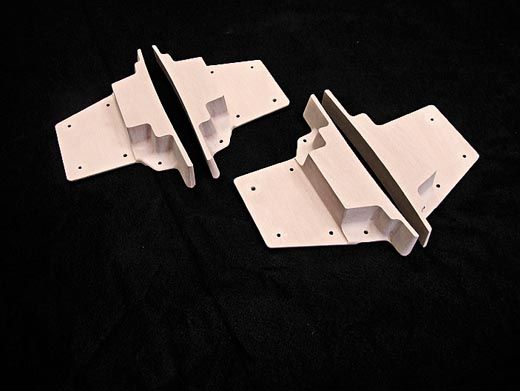

McBurney and his dozen or so volunteers are also digitizing some 20,000 blueprints with the help of modeling software SolidWorks and a scanning device at another company, Bolton Works. This enables 3-D modeling and computer-aided design and manufacturing of new parts, as skilled workers able to make parts by hand are scant and expensive. About 30 percent of the airplane will be newly fabricated.

Yet the team will rely on some traditional construction techniques. “It’s still hand-assembled, and the assembly sequence is critical,” McBurney says.

Daryl Retzke and Matt Sandberg, 20-something engineers, display 3-D blueprints on a computer, which provide manufacturing instructions to a machine.

“For me, this project goes back to the roots of engineering,” Retzke says. “This great airplane was designed by pencil and slide rule.” Studying it piece by piece “makes me a better, more grounded engineer, basically bringing me back to the fundamental instruments and techniques used for design.”

Retzke and Sandberg admit that technology drains some of the excitement. “Computers really take the fun out of designing stuff,” Sandberg says. “[Today] you have software that can do stress analysis. Forty, 50 years ago, they set up giant rigs and did stress tests to see where parts failed” (see “Under Stress,” Then & Now, Apr./May 2009). “I feel the guys who did that kind of work were on a higher level.”

The Corsair’s “official” status confers state approval for incorporating the project and Corsair history into school curricula. The project has also established a NASA-funded engineering internship with the University of Hartford. McBurney wants to get Connecticut companies that worked on the Corsair—United Technologies, Pratt & Whitney, Hamilton Sundstrand, Sikorsky Aircraft, and others—involved in the restoration.

A Connecticut native, McBurney says his infatuation with Corsairs began as a youngster when he saw restored examples at local airports. And he liked “Baa Baa Black Sheep,” the 1970s television series loosely based on Marine Major Gregory “Pappy” Boyington’s Corsair-equipped “Black Sheep” Squadron of World War II. “It’s the first airplane I admired,” he says.

McBurney got his pilot’s license in 1985 at a base flying club while serving in the U.S. Air Force as a gunner on B-52s. After discharge, he maintained and flew B-17, -24, and -25 bombers for aviation museums. Now he devotes most of his time to transforming the Connecticut Corsair into an ambassador for the state’s businesses. Even if he nets a corporate sponsor soon, complete restoration of the airplane to flight-worthy status lies at least three years away.

“I tell the guys, ‘Sometimes you have to put blinders on and ignore the big picture,’ ” he says. “That’s the only way that we can keep working on this. It’s such a phenomenal task, to have the audacity to think you can put something like this together.”

James Wynbrandt lives in New York City and flies a Mooney M20K.