The Long, Strange Saga of the Bremen

After 70 years in exile, the airplane that answered Lindbergh’s flight made a second Atlantic crossing.

:focal(1040x666:1041x667)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/ab/66ab6e6c-09c1-4f6b-b663-74d5990c7043/13a_am2021_rtxi89z_live.jpg)

Eleven months after Charles Lindbergh’s solo Atlantic crossing in the custom-built Spirit of St. Louis, three men boarded a Junkers factory-made, all-metal airplane, the Bremen, and, despite fierce headwinds, fog, and sleet, became the first to fly across the ocean in the other direction. Teddy Fennelly, the biographer of the Bremen’s Irish co-pilot, wrote that the flight “was considered impossible by the experts of the day—including Lindbergh.” Although Lindbergh’s trip from New York to Paris was the second nonstop eastward crossing (eight years after John Alcock and Arthur Brown made the first in an open-cockpit Vimy that landed them in an Irish bog) and the Bremen’s crew achieved a first, the Bremen did not win the lasting fame of the Spirit. Lindbergh’s airplane became a centerpiece at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum. Germany’s premier science museum rejected the Bremen, and it bounced from one American museum to another, until finally, 70 years after its historic flight, it made its way back across the Atlantic to its namesake city. The story of the Bremen proves again that finding a place in history depends as much on timing and social context as it does on virtuosity.

GLOBAL STRATEGY

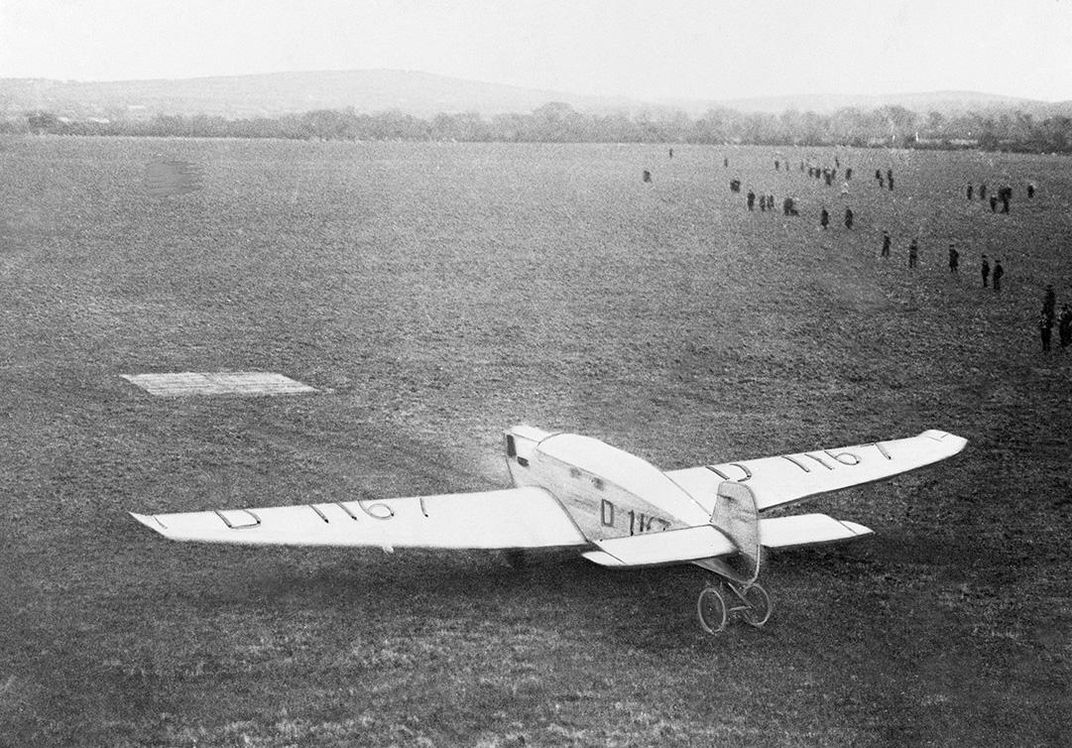

When the Bremen rolled out of the Junkers Dessau plant on July 28, 1927, Hermann Köhl, the 39-year-old Lufthansa pilot who would fly it across the ocean, called it “the greatest plane in existence.” Its low-slung, 60-foot-long, cantilevered wings set it apart from the competition. The Spirit of St. Louis and most other monoplanes of the day needed struts to brace the wings against aerodynamic stress, even though struts increased drag. With its modern wing and corrugated aluminum-

alloy shell, the Junkers W 33 was derived from the world-changing Junkers F 13, a four-passenger transport first flown in 1919. Within five years, the F 13 had come to dominate world air traffic. Still, the political and economic instability of post-World War I Europe and Russia made Junkers seek even more passengers—in the United States.

While the Bremen was being built, the company’s Dessau plant became a center for Hugo Junkers’ Atlantic projects, part of his years-long fight to keep the company from being taken over by the German government. Despite his aeronautical triumphs, a decade of inflation in Germany had brought Junkers to insolvency. Taking advantage of its financial vulnerability, Germany’s aviation ministries forcibly merged part of his company in 1926 with his chief competitor to create the nationalized airline Deutsche Luft Hansa (Lufthansa). Historian Richard Byers, author of Flying Man: Hugo Junkers and the Dream of Aviation, explains that Lufthansa was created not only to take over the privately held airline industry but also to serve “as a mechanism for Germany’s covert rearmament.” Byers believes Junkers was desperate to break into the North American market and saw a transatlantic feat as a way to burnish his brand. If the flight failed, his reputation would be lost, and with it his aviation business.

Only a month after Lindbergh’s flight to Paris, Clarence Chamberlin flew his Bellanca Miss Columbia into Berlin’s Tempelhof airport (having just bested Lindbergh’s distance by 300 miles the day before on a flight from New York to Mansfeld, Germany). Hermann Köhl was one of the 150,000 people on hand in Berlin to greet him. As a Luftwaffe pilot in World War I, Köhl had become an expert in the then-rudimentary skills of night and fog flying. At Tempelhof, he heard about the Atlantic projects from other pilots awaiting Chamberlin’s arrival. Not long after, he traveled to Dessau, where he was introduced to a fellow veteran, Baron Ehrenfried Günther von Hünefeld, 36, a press agent for a German shipping company. The monocled aristocrat, sickly and blind in one eye, was a monarchist who believed a transatlantic flight would win glory for Germany, and he became a chief sponsor of the Atlantic project.

At the same time, however, public opinion was beginning to turn against trans-ocean attempts. In 1927 alone, 16 people had died trying to cross the Atlantic. Sarcastically reminding its readers that April meant “Die Ozeanflug-Saison beginnt! ” (Ocean flying season begins!), the 1928 spring cover of a German magazine featured an illustration of airplanes spiraling down into turbulent waters. As headlines warned “Long Death List Brings Protests Against Flights,” officials in Europe, Canada, and the United States rebuked those who dangled cash prizes for these “foolhardy” flights, and considered banning them.

On its first transatlantic attempt, the Bremen almost added to the casualty list. One month after its factory rollout, the modified W 33 departed from Dessau, with von Hünefeld and Köhl aboard, to fly to America. Battered by fuel-consuming headwinds, Köhl and Czech pilot Fritz Loos became disoriented in fog, and nearly crashed. They recovered but had to turn back.

Lufthansa officials, still at odds with Junkers, warned Köhl not to fly the “inadequate machine” again. Undeterred, the pilot modified the Bremen’s wingtips and increased its fuel capacity. Von Hünefeld lined up 13 investors from among friends in his hometown of Bremen, and Junkers sold him the airplane at a discount. Facing an outright Weimar government ban on cross-Atlantic gambits, the fliers eyed Ireland. Noted Teddy Fennelly, “That little country on the edge of the Atlantic had no such bans and, as a take-off point, would save them nine hours flying time.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/74/53/745367d8-b5e7-45ad-91d4-f395b0eee00b/13c_am2021_10633571_live.jpg)

CLOAKED IN MYSTERY

In his history The Bremen, Fred Hotson observes that by March, German officials were becoming concerned about the “wily Baron” and the “taciturn Köhl.” Authorities warned air controllers to halt the takeoff of any “heavily loaded” aircraft—extra crew or fuel could signal the staging of another attempt. The two adventurers arranged to smuggle two Junkers mechanics carrying fuel and oil to Baldonnel airfield on Ireland’s eastern coast. “The aviators took on pretty much everyone by staging this flight,” says Byers.

Late on Saturday, March 24, 1928, the Bremen was flown from Dessau to Tempelhof airfield. Von Hünefeld sneaked into the aircraft early Monday morning. Köhl drove over a few hours later, jotted “test flight to Dessau” in the air station’s logbook, and got a takeoff stamp.

So as not to raise suspicions, the crew postponed takeoff until 8 a.m., their normal test-run time. Köhl taxied the aircraft to a grassy field to avoid a potential runway blockade. The Bremen made its furtive takeoff while authorities worked belatedly on a seize order. Lufthansa fired Köhl immediately.

Joining him and von Hünefeld for the nine-hour, 816-mile journey was Arthur Spindler, 37, a former sergeant-major in Köhl’s bombing squadron. Junkers fretted that Spindler had spent too many post-war years on the ground, and once in Ireland, he was replaced as copilot by a 29-year-old commander of the Irish Army Air Corps, James Fitzmaurice. Fitzmaurice was a World War I Royal Air Force ace, but he didn’t speak German. The crew communicated with hand signals.

Barricading themselves behind barbed-wire at Baldonnel airfield, the three methodically planned their assault on the Atlantic. Influenced by Köhl’s reputation as “Europe’s most cautious pilot,” Wall Street odds on their success improved, dropping from one in a hundred to a mere one in four.

Seventeen rain-drenched days later, ships crossing the Atlantic telegraphed that the weather was changing. Von Hünefeld wrapped a revolver in oiled silk (intending suicide in the event of a crash), and a steamroller tried to wring out the runway’s soggy turf. Throttle opened, chocks removed, the Bremen was wheels up at 5:38 a.m. on April 12, barely clearing wandering sheep. Its destination: Long Island, or as Fitzmaurice said, “Mitchel Field or heaven.”

Things didn’t go well. The crew’s magnetic compass eventually became insensible. The instrument panel lights broke. Having omitted a radio to save weight, the crew didn’t receive ships’ warnings of fog-shrouded icebergs. The uninsulated, unpressurized airplane “trembled in every joint,” Köhl later reported. Fog was followed by a blizzard; a leak sprang in an oil line. Thirty-plus hours in, they were low on fuel and lost.

Spotting what Fitzmaurice believed was a “ship frozen in the ice,” the pilots landed on what turned out to be the iced-over reservoir of tiny Greenly Island, two miles from the mainland in eastern Quebec province. There was a brief moment of stillness and relief; then the ice rind broke, pitching the Bremen forward and denting the propeller and undercarriage.

The contrast between Lindbergh’s landing and the Bremen’s are worth noting: Roughly 100,000 Parisians had greeted Lindy at Le Bourget airfield on a warm May evening. Frigid Greenly Island was populated by a Canadian family of eight who, unfamiliar with airplanes, deduced that a “flying fish” had pierced the sky. It was Friday, April 13, 1928.

The island’s lighthouse keeper, John Letemplier, helped the fliers absorb the news that they were 1,077 miles short of Mitchel Field. Letemplier’s brother walked two miles across the frozen Strait of Belle Isle to the home office of Alfred Cormier, whose telegraphs unleashed an explosion of excited reactions, bestowing fame on the fliers.

The Bremen never flew again.

GATHERING OF HEROES

Three days later, aviator Herta Junkers, Hugo’s 30-year-old daughter and vice president of Junkers North America, flew north from New York in a Junkers F 13 with two pilots. A wing design specialist who “imposed her strong will and personality on everyone here,” according to New York Times reporter B.W. Nyson, she supervised the Bremen rescue mission while 60 reporters camped at the Western Canadian Airways base in Lac Sainte-Agnès, 700 arctic flying miles from Greenly, waiting breathlessly for word.

The rescue developed into a worldwide news story of its own and turned somber when one of its pilots, famed North Pole aviator Floyd Bennett, developed pneumonia while attempting to deliver supplies to the stranded crew. Now there were two rescue dramas. Lindbergh himself carried anti-pneumonia serums in the Army’s fastest airplane to Bennett’s bedside in Quebec City, but for naught. He died the next morning.

The following day, before boarding the rescue mission’s Ford Tri-motor for the trip from Greenly, the ocean-crossers bid goodbye to their stalwart airplane. “Good old Bremen, you brought us through, and now we have to leave you on the last, easiest lap,” whispered Fitzmaurice. They headed to Arlington National Cemetery to pay respects at Bennett’s grave. Three days later, they were cheered by an estimated two million in a Manhattan ticker-tape parade.

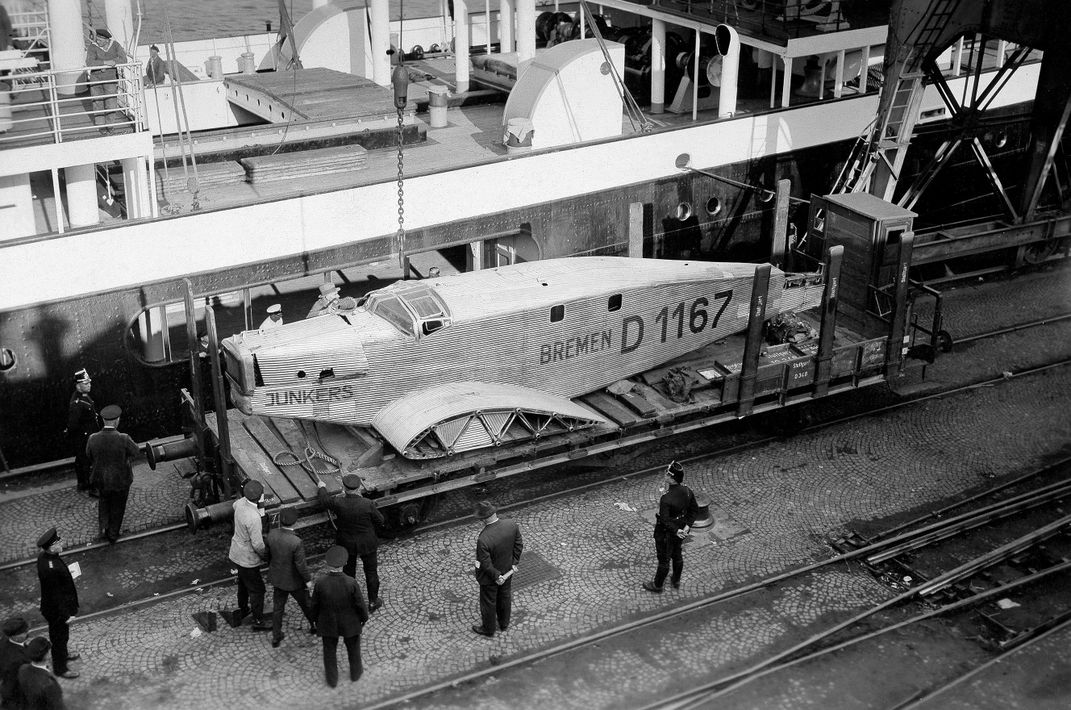

Touched by the warm reception, the trio presented the Museum of the City of New York with the Bremen’s propeller and Fitzmaurice’s ceremonial sword. After a heady nine-city tour, the Bremen crew took the oceanliner Columbus back to Germany in June. Lufthansa rehired Köhl.

The Bremen, though, remained stranded on Greenly. In mid-May, Herta Junkers asked the U.S. War Department to help her pilot, Fred Melchior, reach the island. The Army Air Corps’ chief, Major General James E. Fechet, signed on to fly this third rescue. Melchior parachuted from a Loening OA-1 amphibian to reach the Bremen, which had been towed to a hill on the mainland.

As if cursed, the week-long effort was marked by its own misfortunes, and ended with the W 33 loping downward to a crash. When the pilots heard the news, “each of us felt we had lost his own child,” reported von Hünefeld.

In Washington, D.C., Paul E. Garber, then an assistant curator in the aeronautics section of the Smithsonian, launched a crusade “to get it here.” He wrote a top Smithsonian official that it would be an “honor” to travel to Greenly to “pack it up,” envisioning that “it would flank the Spirit of St. Louis and thus put together the planes whose paths crossed in memorable flights.”

Meanwhile, von Hünefeld offered the Bremen to Munich’s prestigious Deutsches Museum. Oscar von Miller, its founder, rejected the gift, citing the museum’s 1903 statute that limited collections to “masterpieces” or prototypes of scientific and technological advancement. According to Dr. Wilhelm Füssl, archivist at the Deutsches Museum and Miller’s biographer, Miller praised the “flying boldness” but stressed that the Bremen was not a new ocean-flying machine, merely a retrofitted Junkers, whose original the museum owned.

In turning down the offer, Miller bucked the sentiments of an unusually ecumenical group that included Weimar leaders, a surging Nazi movement, German-American politicians, intellectuals, artists, the Bavarian State Ministry of the Interior and the Reich Ministry of Transport. Von Hünefeld published a furious editorial in Deutscher Adelsplatte, a newspaper influential among German aristocrats.

Von Hünefeld’s politics invited plenty of detractors. He displayed the Imperial German flag on the Bremen and continued close ties with the exiled kaiser and crown prince. Many saw this as a direct challenge to the Weimar Republic. Protesters in Cologne, Dessau, and Bremen decried his nationalistic behavior. As the controversy raged, Miller stuck to his guns. Whether he did this out of principle or to shield the museum from the cross-currents of German politics is, according to Füssl, unknowable.

The airplane drew large crowds at exhibitions in Berlin, Dresden, and Bremerhaven, but von Hünefeld decided he would give his prize possession to New York City. When the baron died in February 1929, he made good on his declaration, bequeathing the Bremen to the Museum of the City of New York. Years later, the Smithsonian’s Garber glumly concluded: “It is evident that he did not know of our desire for it.”

Amelia Earhart was among the 17,000 onlookers who gathered for its unveiling beneath the celestial dome of New York’s Grand Central Terminal on May 21, 1929. The City Museum, lacking space for von Hünefeld’s gift, loaned the airplane to a fledgling science institution, the Museum of Peaceful Arts, which secured the Grand Central lease and then, in December 1930, loaned the Bremen to the Smithsonian. Garber’s dream fulfilled, the pairing of the Spirit and the Bremen, aviation’s Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, lasted five years.

Time was less kind to Junkers and his company. Beginning in 1933, Hitler’s air ministry subjected Junkers to interrogations and eventually house arrest to get control of the remnants of his firm, licenses, and valuable patents. Byers believes that only when the state expanded “the circle of intimidation to include his family” did Junkers surrender his business. He died in 1935. The Junkers name remained on Nazi aircraft but its aspirational Bauhaus-designed logo of a “Flying Man” was replaced with swastikas.

A SUDDEN MOVE

On April 10, 1936, Carl W. Mitman, the Smithsonian curator who oversaw Garber’s aeronautical division, advised museum directors that the explorer Lincoln Ellsworth had offered to donate his Polar Star, the Northrop Gamma that he had flown over Antarctica in 1935. Mitman wanted to use the Bremen’s spot for the acquisition. “Our collection will then be confined exclusively to American designs and after all let it be up to the Germans to preserve German designs,” he proffered. Two weeks later, the Museum of the City of New York was asked by the Smithsonian to take back the Bremen. By that time, Hitler had become chancellor, and he traveled in a Junkers Ju 52. Perhaps the association of the Junkers name with Hitler’s growing aggression influenced Mitman’s decision.

The City Museum quickly conveyed its title to Henry Ford’s 200-acre museum complex in Dearborn, Michigan. As pioneering industrialists, Ford and Junkers had a fraught history. Ford revered Junkers as a “role model” but appropriated his all-metal designs, leading Junkers to successfully sue him twice. They also held serious but unsuccessful negotiations to create an international airline network. In his early 70s, Ford, an idiosyncratic collector of nearly a million objects, may have had a simple reason for the acquisition. As expressed by his chief early-airplane advisor, Frederick A. Hoover, the Junkers had “historical value.”

J. Marc Greuther, who became the Henry Ford’s chief curator decades after the transfer, still believes the Bremen deserves public display. “This gets to the power and purpose of museums—you see its scars, its lightness,” he said. Greuther imagined von Hünefeld inside “a vulnerable vessel hurtling into the night.” It was “both outrageously brave and at the same time utterly absurd.” The Ford museum displayed the Bremen for 61 years.

In 1997, a group of flying enthusiasts called “We Bring the Bremen to Bremen” came knocking. Citing von Hünefeld as an honorary member, Dr. Bernd Hamacher, secretary of the society, spoke of their civic pride and admiration for the Bremen pilots. The Henry Ford approved a permanent loan stipulating that only Lufthansa mechanics supervise the airplane’s restoration.

Winging east, two German Air Force Transall C-160s transported crated sections of the Bremen directly over Greenly Island, a tribute requested by the Bremen society. Today, the restored airplane, polished to a glossy sheen that nearly disguises its rugged history, rests in the rooftop exhibition hangar of Bremen Airport’s Terminal 3. “We believe the plane is where it should be,” Hamacher said.

With hindsight, an overlooked byproduct of the Henry Ford’s 61-year stewardship emerges. If von Hünefeld had gotten his wish 93 years ago, the Bremen would have been destroyed, observed aviation historian Paul Zöller, when 5,000 incendiary bombs rained down on the Deutsches Museum during Allied air raids in 1944. Many early original airplanes were destroyed.

Rejection, it seems, saved the itinerant Bremen, the aircraft that once carried von Hünefeld, Köhl, Fitzmaurice—and Junkers himself in a way—through storm clouds and across an ocean.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/43/b6/43b6597a-6823-4821-8275-30c210a42b15/junkers-sepia.jpg)