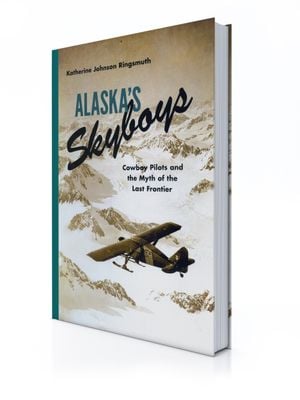

Alaska’s Skyboys

Cowboy pilots and the myth of the last frontier.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/24/75/24759ba1-62e1-4946-8abf-dad497c796bc/24_cas_plane_taing_off_from_sandbar_on_river_2-40-12.jpg)

Katherine Johnson Ringsmuth is a former cultural resource historian for the National Park Service. She currently teaches U.S. and Alaska history at the University of Alaska-Anchorage. She is the author of Alaska’s Skyboys: Cowboy Pilots and the Myth of the Last Frontier (University of Washington Press, 2015).

Air & Space: Why did you decide to write this book?

Ringsmuth: I started wondering: If aviation is considered a 20th century innovation, then why do we celebrate bush pilots like 19th century cowboys? I think that we should move beyond the narrow, frontier narrative when explaining the role of aviation in the North. By understanding Alaska’s bush pilots more broadly, we gain a better appreciation for their feats and their failures. Rather than conquerors, they become students of nature.

Alaskans have long had a reputation for being bold and ruggedly self-reliant. Is it any surprise that Alaska’s pioneering bush pilots might have had some of these same qualities?

Most people, including Alaskans, would describe bush pilots as self-reliant, individualistic, defiant, and daring individuals. The perception of bush pilots as modern-day cowboys, who embody the frontier spirit of Alaska, remains a powerful narrative that resonates with most Americans.

What does Alaska’s general aviation community today think of the legendary bush pilots of yesteryear?

Alaskans consider our golden age of aviation as a period lasting roughly between 1924—when the first commercial flights occurred—to 1938, when federal government regulated routes. During this time, only a handful of people piloted airplanes. Even fewer flew in them, and fewer less understood how aviation worked. Harold Gillam, Bob Reeve, Kirk Kirkpatrick and Merle “Mudhole” Smith: They were part of Alaska’s elite fraternity of skyboys in the 1930s. In anecdote after anecdote, these fliers are presented as pathfinders, cowboys, blazing trails in fixed-wing biplanes. But, for the most part, these are second-hand interpretations, and do not come from the fliers themselves.

Do you think today’s bush pilots are more respectful of safe flying practices than their forebears?

Without question, today’s pilots have access to better maps, aeronautics equipment, training, and communications technology, and are mandated to follow state and federal safety regulations, but whether they were flying in the 1930s or in the 2000s, once airborne, there is no exaggeration: Wrangell Mountain skyboys navigate a skyscape that contains some of the highest and most rugged terrain in Alaska. The unpredictability of Alaska’s weather meant that even the safest and most competent pilots crashed.

Alaska’s lack of road- and railways has contributed to the state’s robust aviation industry. And aviation has allowed Alaskans to live the wilderness lifestyle in remote areas. So at this point, do you think some Alaskans would actually feel threatened by the building of plentiful roads and highways, since doing so would lead to a loss of wilderness?

Historically, Alaska roads have provided important economic and a physical benefit to communities they connect, but roads in Alaska can be psychological too. Being cut off from the road system and the rest of the world can adversely affect a small-town society, but this was not the case in Cordova, the onetime terminus of the Copper River & Northwestern Railway. In fact, the community not only accepted, but embraced, its isolation after the railway was abandoned in 1938. One reason was, as you point out, its long-standing association with aviation, which connected Cordovans with the world when they chose to—not the other way around.

You frequently travel by air in Alaska. Are you still impressed by the beautiful views of nature you see during these flights?

Although I am afraid to fly, the view from an aircraft’s vantage point never ceases to amaze me. It is only from this perspective one can truly appreciate the insignificance of our manmade footprint compared to the overwhelming power of Alaska’s dynamic landscape. While flying over the Wrangell Mountains, you see glaciers that have moved earth like bulldozers, and massive rivers that—over the centuries—have flooded, eroded, and ultimately rearranged the topography.