Reviews and Previews: Prodigal Son

A troubled man, Gregory Boyington found redemption commanding a U.S. Marine fighter squadron in the South Pacific

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Reviews_and_Previews_0911_1_FLASH.jpg)

Black Sheep: The Life of Pappy Boyington

by John F. Wukovits. Naval Institute Press, 2010. 249 pp., $34.95.

Gregory “Pappy” Boyington shined as a U.S. Marine fighter pilot during World War II, but out of the cockpit, he struggled with life. This biography, written by World War II Pacific theater expert John Wukovits, tracks Boyington’s evolution from a young, hot-tempered, debt-riddled, alcoholic pilot to an old, hot-tempered, debt-riddled, alcoholic pilot. “Without the sense of self-value he gained whenever he took to the skies, without the feeling of being needed and of contributing to something larger than himself, Boyington was a man adrift, a lost soul searching for meaning,” writes Wukovits.

The author paints a dark portrait of Pappy. Before the war, when Boyington was up to his ears in debt, in a dying marriage, and aching to fly against the Japanese, he resigned his Marine Corps commission to join the American Volunteer Group, the Flying Tigers. It wasn’t just for the adventure and to put distance between himself and his family, but also for the Flying Tigers’ hefty salary and the huge bonuses for each Japanese airplane shot down. Despised by commander Claire Chennault for ignoring his lectures on engaging the legendary Zero with the Tigers’ slower P-40 Warhawks, Boyington rarely got to fly combat. Resigning after crashing a P-40 while flying drunk, he made his way back to the States and ended up parking cars in a Seattle garage. But the U.S. needed experienced pilots, so Boyington recovered his Marine commission and ended up in the South Pacific, still drinking and away from the action.

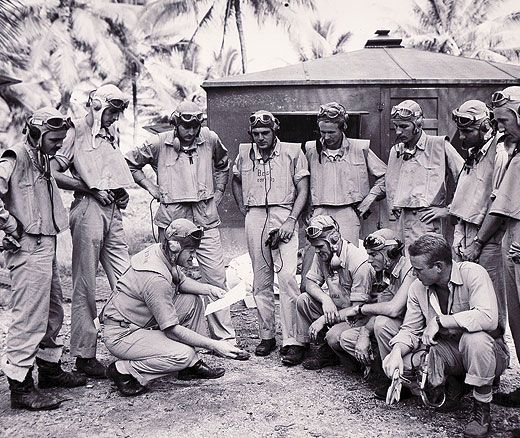

Then a sympathetic superior offered him command of a new Marine squadron, one for which Boyington could pick the pilots. Contrary to legend, none of the fledglings were misfits or jailbirds. They were fine fliers, and during the day, Boyington honed their combat skills in their new F4U Corsairs, while at night he lectured them in the bar. “He was the best aviator out there,” said one of the younger pilots. They revered his every word and gave him the nickname Pappy because he was slightly older, infinitely more experienced, and the “bravest SOB.” And they gave themselves the name Black Sheep Squadron, but only after the Corps scrapped their first choice: Boyington’s Bastards.

Over the next several months, Boyington led the Black Sheep across the South Pacific. He was shot down on January 3, 1944. Fished out of the sea by the Japanese, Boyington spent the next 19 months as their sober guest, finding a nobility in resisting their extreme cruelty. After VJ Day, he arrived home and received the Medal of Honor awarded to him when he was MIA. He considered entering politics, but he started boozing again and drank himself through a host of jobs before being consumed by bronchitis, emphysema, and lung cancer. (He died in 1988.) Truthfully, the best time of Boyington’s life was war.

Along with being a biography, the book is nearly a primer for World War II fighter combat. But it has an appropriate title. If you’re looking for hagiography, try the 1970s TV series “Baa Baa Black Sheep.”

Phil Scott’s next book is titled Then and Now: How Flying Got This Way.

First Contact: Scientific Breakthroughs in the Hunt for Life Beyond Earth

by Marc Kaufman. Simon & Schuster, 2011. 224 pp., $26.

In his new book, First Contact, science writer Marc Kaufman starts with a simple premise: The discovery of extraterrestrial life is just around the corner. This may seem to be the realm of science fiction, but as Kaufman shows in this fascinating book, scientists around the globe are conducting a serious search.

There are stories of creatures that live in conditions hostile to most other kinds of life, such as miles into the atmosphere or buried in Antarctic ice. Kaufman accompanies one Belgian scientist traveling more than two miles into a South African platinum mine to discover nematode worms living in the rock.

In Australia, astronomers search for exoplanets, hoping to find one similar enough to Earth that it might support life. On the northern tip of Norway, scientists test equipment for future missions to Mars. And in New Mexico, a microbiologist tries to figure out if a mysterious substance called desert varnish is the product of chemistry or biology.

The question of what exactly life is turns out to be so complex that scientists haven’t yet agreed upon an answer. And they still debate the meaning of decades-old studies, including the 1952 Miller-Urey experiment that sought to re-create the origins of life with a mixture of water, gases, and an electric current.

Kaufman notes that the eventual discovery of alien life is unlikely to be a “Eureka!” moment; any such find will require years of research to confirm. But those curious about how that hunt is taking place will find a good overview here.

Sarah Zielinski is an associate editor at Smithsonian magazine.

Mission to Berlin: The American Airmen Who Struck the Heart of Hitler’s Reich

by Robert F. Dorr. Zenith Press, 2011.328 pp., $28.

After interviewing dozens of pilots and bomber crewmen, Air & Space contributor Robert F. Dorr has crafted a book that brings to life the daylight bombing raids the U.S. Eighth Air Force mounted against Germany’s capital. The following excerpt is from a chapter entitled “Squabbling.”

A typical Me 262 was powered by two 1,984-pound-thrust Junkers Jumo-004B axial-flow turbojet engines, was armed with four 30-mm nose cannons, and reached a speed of 540 miles per hour. “By the time the German jets went into production, it was too late and nothing was going to change the outcome of the war,” said British aviation writer Jon Lake. Me 262s shot down about one hundred Allied aircraft by war’s end, but the Allies also shot down dozens of them. Bomber crewmembers thought about the Me 262 on every mission, heard about it in many briefings, and probably credited it with more than the German jet was really capable of.

“We heard about them around January 1945,” said [B-17] copilot First Lieutenant Robert Des Lauriers. “We saw them. Man, would they go by fast! On a mission in January, I witnessed an Me 262 flying straight up with a Mustang on his tail, also flying straight up. In briefings, we were told to be alert for them and especially to make note of where they were. We were very much aware that the German jets were very vulnerable when they were taking off and landing. Our intelligence guys wanted to put Mustangs into a position to pick them off in the airfield pattern.” By this time, Mustangs and even portly P-47 Thunderbolts were regularly blasting the German jets out of the sky.

“I saw a few,” said Fancy Nancy Technical Sergeant Ray Fredette [a B-17 nose gunner]. “The jets I saw weren’t attacking us. They were observing our bomber stream from quite high up and off to the side. The P-51s took off after them. Just as the P-51s got close, the jets turned on the power and it looked like the P-51s were left standing still.”

Aerotropolis: The Way We’ll Live Next

by John D. Kasarda and Greg Lindsay. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011. 466 pp., $30.

This is not a flying book. Nor an airplane book. What, then, is it about? I’m tempted to say it’s about hubs, because at a conservative estimate the word “hub” appears about 500 times in these 400-plus pages, often three or four times per page, and once five times in four sentences. It’s even used as a verb, as in: “It makes more sense to hub that out of Dubai than Johannesburg.”

Essentially, the book reports on businesses that are made possible by airlines, airports, and air cargo: for example, the global flower business as represented by the Aalsmeer flower market, located six miles from the hub known as Amsterdam’s Schiphol airport. Aalsmeer is where some 20 million cut flowers arrive daily from Africa, are auctioned off, and then sent on to other hubs in Europe, the United States, and Japan. A second example is the global seafood business, the current hub for which is Germany’s Frankfurt airport, “where a veritable Garden of Eden is kept on ice.” And so on.

The “aerotropolis” of the title is simply the hub itself plus the total set of businesses associated with it, including those that house, feed, entertain, and otherwise serve the needs of passengers who fly to, connect through, or work there: hotels, offices, malls, warehouses, entire cities. Cities have always arisen at ports. What’s new are the speed of jet travel, the continuing increase in the number of travelers, and the complexity of the hub system, which together will supposedly transform everything.

But the future the book describes is largely here already, which makes it hard to take the subtitle seriously. If you’re not a fan of business literature, give this one a miss.

Ed Regis is a frequent Air & Space/Smithsonian contributor.

At a Glance

Airborne Dreams: “Nisei” Stewardesses and Pan American World Airways

by Christine R. Yano. Duke University Press, 2011. 219 pp., $22.95.

Japanese-American women who began working as stewardesses for Pan American World Airways in 1955 tell their stories.

London’s Airports: Useful Information on Heathrow, Gatwick, Luton, Stansted and City

by Martin W. Bowman and Graham Simons. Pen & Sword Aviation, 2011. 138 pp., $29.95.

Aviation enthusiasts and passengers alike will enjoy this book, which offers histories and archival and contemporary photographs of London’s five main airports.

Revolutionary Atmosphere: The Story of the Altitude Wind Tunnel and the Space Power Chambers

by Robert S. Arrighi. NASA, 2010. 392 pp., $39.95.

The history of a facility in Cleveland, Ohio, that played a major role in the development of jet aircraft in the United States.

USAF Interceptors: A Military Photo Logbook (1946 – 1979)

Compiled by M.J. Isham and D.R. McLaren. Specialty Press, 2010. 128 pp., $24.95.

A look at the great aircraft that the Air Defense Command flew during the cold war.

The Luftwaffe’s Blitz: The Inside Story, November 1940 – May 1941

by Chris Goss. Crecy Publishing, 2010. 264 pp., $36.95.

First-hand accounts from the Luftwaffe air crews who terrorized London with night raids during World War II.

Airlines of the Jet Age: A History

by R.E.G. Davies. Smithsonian Institution, 2011. 461 pp., $99.95.

Davies, a recently retired curator at the National Air and Space Museum, is an authority on commercial air transport. His latest book is a comprehensive reference work on jet airlines, from the early 1960s to the present.

Ed Regis is a frequent Air & Space/Smithsonian contributor.