Crash in the Canary Islands

A new book explains how a series of misunderstandings by aviation professionals led to catastrophe.

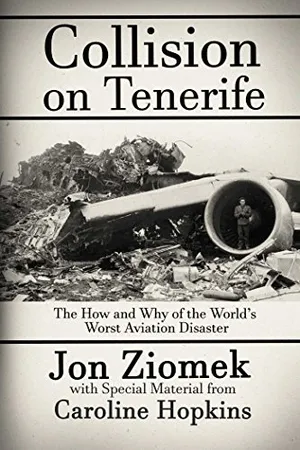

In Collision on Tenerife, Jon Ziomek has written a riveting account of the errors that unfolded before the worst civil aviation disaster in history, when on March 27, 1977, two Boeing 747 passenger jets—KLM Flight 4805 and Pan Am Flight 1736—collided on a runway at Tenerife island, killing 583 people. Ziomek spoke with Air & Space senior associate editor Diane Tedeschi in April.

Air & Space: Why did you decide to write this book?

Ziomek: Many years ago, I met Caroline and Warren Hopkins, two of the crash survivors, who lived near me in suburban Chicago. Although Caroline had written a diary of their experiences as passengers on the Pan Am 747, they wanted the help of a professional writer in getting their story told publicly.

This accident seemed so preventable. What was the critical turning point?

The Spanish government, which governs the Canary Islands, took more than a year before issuing its final report. There were several contributing factors—for example, confusion on the part of both 747 flight crews in understanding taxiing instructions from the air traffic controllers—but a key reason was that the captain of the KLM jet did not have control-tower clearance when he began his takeoff roll. No one in the control tower or the Pan Am cockpit knew this because the runway was obscured by fog, and the airport at Tenerife didn’t have ground radar.

Was there any attempt by the press or accident investigators to paint the captain of the KLM aircraft as the bad guy?

In the months after the crash, before the official report was released, the three different nations [Spain, the Netherlands, and the United States] tended to shift blame away from themselves. The Dutch government originally noted that the Pan Am airliner had missed its assigned turnoff from the runway, which was true. It was also true that the Spanish air traffic controllers had been less than clear in their instructions to both flight crews. But the KLM crew did get much of the bad publicity because of the captain’s unilateral action, and when the final report was released, the KLM crew received the largest portion of the blame.

What is the most surprising or shocking thing your research uncovered?

My answer to this question has several parts. First, neither of these airplanes was even supposed to be at Tenerife airport, let alone on the same runway at the same time. They’d been diverted from their planned destination [Las Palmas on the nearby island of Gran Canaria] because of a terrorist bomb. I found an astonishing 11 separate coincidences and mistakes, most of them minor, that had to fall precisely into place for this accident to happen. Second, a human point: I was touched, even moved, by the number of survivors who were willing to discuss personal details of that day and how it had affected their lives afterward.

Was there a financial settlement for the crash victims?

Yes, all survivors and families of victims received settlements, per an international aviation agreement that was in place at the time.

Did the airline industry make any adjustments after the accident?

First and most notably, air controller language for international aviation was standardized to prevent confusing flight crews. Second, many airports now have light systems in place—just like traffic lights for cars—to warn taxiing aircraft when runways are in use. Third, Tenerife’s aviation officials moved most of their flights to a new airport that has ground radar. The odds of an accident like this one were remote to begin with. I really believe it’s almost impossible for such an accident to happen again.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.