Born in the 1960s, The Sport of Hang Gliding Still Hangs On

It may not be as popular as it once was, but its fans say it is still the purest form of flight.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2b/6f/2b6f1780-d246-4d41-984d-391548f240ca/hang-gliding-opener.jpg)

“We first flew in dreams, but the dream of flight has become real,” the narrator says. The image on the giant screen is mesmerizing: Above massive volcanic islands reaching up from the ocean floats a tiny triangular form. This is the first shot of the hang gliding scene from To Fly!, the iconic IMAX film made for the opening of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in 1976. It has been playing for more than 40 years, and for many, it’s their first encounter with hang gliding.

In the scene, pilot Bob Wills hangs below the wing, shifting his body to exert control over the impossibly simple craft. He soars between mountain peaks, then climbs, stalls, dives, and swoops high above the water. When the film was made, hang gliding was emerging from its infancy and about to experience a popularity boom.

Building on a tradition of homemade gliders starting with Otto Lilienthal, Octave Chanute, and the Wright brothers, flying enthusiasts in the 1960s and ’70s fulfilled the dream of accessible, inexpensive, birdlike flight for humans. Hang glider pilot Erika Klein, communications manager for the United States Hang Gliding and Paragliding Association (USHPA), explains why the sport caught on. “If you ever flew a kite and wished you could be flying up there with the kite—[but] flying free, flying away,” she says, “that’s basically what it is. It’s just a big kite, and you’re attached to it, and you can go pretty much wherever you want.”

The fundamental design of the hang glider has remained fairly constant since it came together in the 1960s. The pilot lays prone, suspended in a harness at the center of gravity beneath (usually) a swept wing. The wing is made of fabric and metal tubes and reinforced by external bracing and internal spars and ribs called battens. The top half of the pilot’s body pokes through a triangular frame—two downtubes and the control bar. Pulling in on the control bar causes the glider to dive and gain speed. Push out and the glider climbs and loses speed. Shifting the body left turns the glider left; shifting right turns it right. Foot launches are made off hills, dunes, mountains, and cliffs, but gliders are also towed aloft by airplanes, trucks, ATVs, and even scooters.

“You can fly slowly, in control—the thrill of maneuvering through the sky,” says Bruce Weaver, who has taught hang gliding at Kitty Hawk Kites for more than 30 years. “It’s something that’s hard to describe; once you start doing it, it’s something you never want to stop.”

Weaver’s right—it is indescribable, but I’ll try. In almost every other kind of flight the pilot or passenger is seated, and the apparatus of the flying machine is visible—you see the fuselage around you, the wing above or below you. But in a hang glider, the wing is mostly out of your field of view. You look out ahead and see nothing but the sky and landscape. You look down and there’s nothing between you and the ground but air. You hang from the straps in the harness and your body is free to move. The air is tactile, the wind in your face and ears. The clouds are so close you can actually touch them.

I’ve launched off training hills, taking off with nothing but my own foot power (and a gravity assist). To run and fly—even such a simple flight—is a dream come true. As Dennis Pagen, the leading authority on hang glider safety and training says, “When you dream of flying, do you fly around seated in a chair or are you floating like Superman?”

* * *

But for all its appeal, by every metric of participation—the number of manufacturers, schools, new pilots getting rated—hang gliding is in decline and has been for years. There are multiple factors at play: lack of exposure, persistent negative perceptions of safety, an aging pilot population, and new ways to see Earth from above, like Google Earth and drones.

Added to that is paragliding, hang gliding’s biggest competitor. A paraglider is a soft-wing glider that fits in a pack that can be carried on the pilot’s back. The pilot sits in the harness and foot launches from mountains and hills. It gained popularity in the United States about the time hang gliding was at its peak. Paragliding also appeals to younger pilots in greater numbers. “Paragliding is what hang gliding used to be. It’s slow, easy to fly, perceived to be very stable, and obtainable,” says Weaver.

“Perceived to be safer” is a phrase I heard often from hang glider pilots talking about paragliders. Like hang gliding, it carries its own risks. With hang gliding, says Klein, “Most accidents are a result of pilot error. It’s very rarely the hang glider failing in midair.” In addition to pilot error, a paraglider’s sail can deflate, causing the pilot to lose lift and control. But, says Kitty Hawk Kites’ founder John Harris, “Because of the perception of paragliding being easier and more portable, the sport is continuing to grow, while hang gliding is not.”

Hang gliding veterans acknowledge the sport’s eclipse by paragliding. “Hang gliding to me by far is the more enjoyable of the two,” says Martin Palmaz, executive director of USHPA and a 20-plus year paraglider pilot. “The speed, the three-axis control, the proximity to the wing, the control system—hang gliding is more interesting. Paragliding is easier for me to do, to go out and enjoy some free flying, but in terms of the experience, I think hang gliding is far superior.” Tiki Mashy, owner of Cowboy Up, a gliding school near Houston, suggests a few other advantages. “Hang gliding is harder to learn but easier to master,” she says. “And hang gliders can fly in a much wider variety of conditions than a paraglider.”

The risk in hang gliding, however, is not just perceived. “There’s risk every time we fly, and all pilots accept that,” says Klein. Wills Wing, a hang glider manufacturing company, estimates on its website one death per thousand participants. According to the site, that statistic makes hang gliding more dangerous than driving a car. But when student flights are factored in, the rate decreases, given the large number of student flights with very rare fatalities. According to USHPA’s annual fatality reports, there were 10 hang gliding fatalities in 2015, eight in 2016, one in 2017, and two by June 2018.

The statistics don’t tell the whole story, says Klein; the sport is unregulated, and we don’t know how many flights are made each year. “It’s important to note that there may be many more hang glider pilots than are shown by USHPA membership numbers,” she says, “as being a member of USHPA isn’t required by the FAA to hang glide.”

In terms of training, equipment, and self-regulation, safety is taken far more seriously than it used to be. “We did have a high accident rate in the early days, and that perception has stayed with us,” says Pagen, who wrote the first books of hang glider training and safety. “Not the accident rate, but the public perception, which is not always logical.”

The enduring public perception of danger has affected hang gliding’s viability. USHPA ran out of insurance companies willing to cover its members and has set up its own company to self-insure.

Adding to hang gliding’s challenges is the aging of its core population. “The baby boomer generation propelled hang gliding in the beginning,” Harris says. “Ten years ago, we still had a lot of baby boomers taking lessons in their 50s and 60s.” “There’s flying opportunities all over the country,” says Palmaz. “It’s not that the opportunities aren’t there; it’s that they’re not obvious.” Adds Weaver: “I don’t think that hang gliding is geographically too far away. It’s mentally too far away.”

And as luck would have it, in November 2018 hang gliding was suddenly back on the public’s radar with a story about a very dangerous flight. A video went viral of an American tourist hanging on for his life after taking off from a Swiss mountain on a tandem flight. His instructor had neglected to connect his harness to the glider. Chris Gursky clung to the control bar and the instructor’s leg as the pilot struggled to get the glider to the ground. Gursky suffered relatively minor injuries when he let go as the glider came in to land. But in every interview he gave after the accident, he said he would absolutely want to go hang gliding again—properly.

* * *

The sport has multiple sources of origin. “It’s like the invention of the TV—it’s a complicated story,” says Billy Vaughn, author and a longtime pilot and instructor at Kitty Hawk Kites. “Barry Hill Palmer built one in California in 1961. Flew it hanging from his armpits.[Australian pilot] John Dickenson gets the credit for the control bar and the hang strap—actually hooking into the center of gravity and using your weight to shift around it. But the wing is pure Rogallo.”

Vaughn is writing the first comprehensive biography of Francis Rogallo, the NASA engineer who used a cloth cabinet-skirt to test his eponymous wing. Rogallo first marketed the invention on a small scale as a toy, but when it caught the attention of Wernher von Braun, NASA explored its potential in the recovery of rocket booster engines.

While NASA didn’t end up using the wing, it received attention in popular magazines, and the doors for hang gliding opened. “It was really the Rogallo wing that brought [hang gliding] flight to the masses,” says Pagen. “It was so light, so easy, and intuitive. It could have used more performance—it only had a 4-to-1 glide [ratio], but it was stable unless you got it into extreme situations.”

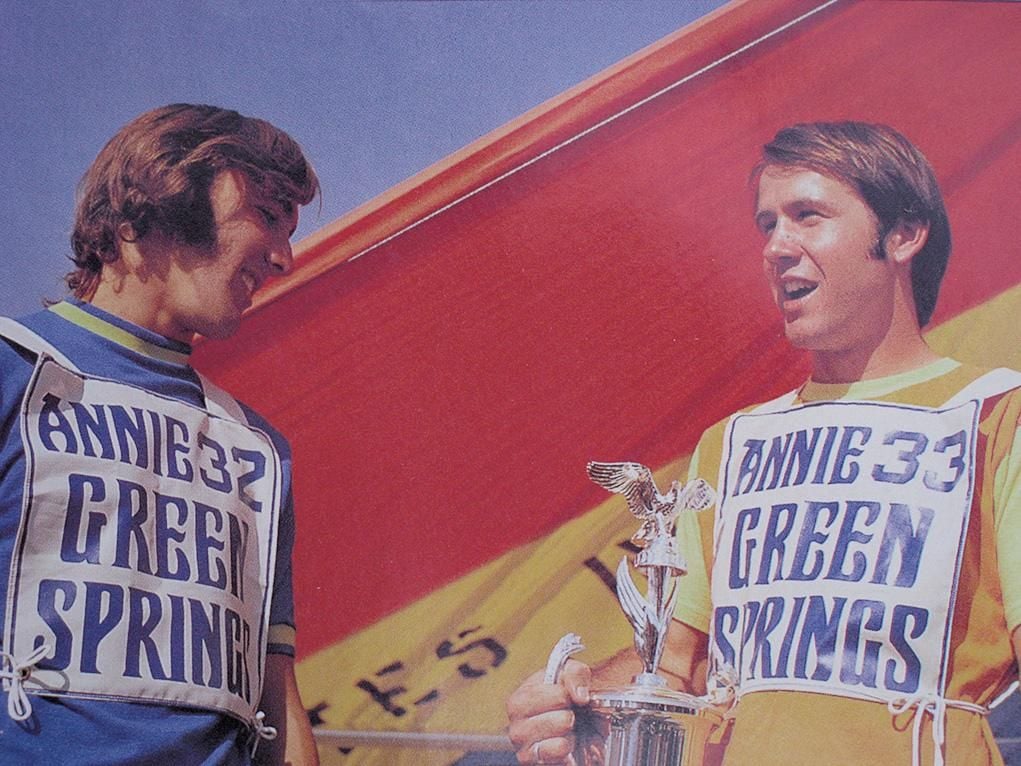

To see the feral origins of hang gliding as a popular sport, do a search on YouTube for the 1971 Otto Lilienthal Universal Hang Glider Championship—the first of its kind in the United States, held at Corona del Mar, California. Young enthusiasts run down grassy hills, holding homemade flying contraptions, some of which were actually made from plastic sheeting. If they do launch, the pilots simply hang by their armpits and swing their legs around in an attempt to steer the glider by weight shifting. There’s more than one crash and more than one run down the hill without getting airborne. The film ends with a glider crashing into the cameraman. National Geographic covered the 1971 event; the article “got a lot of people building hang gliders,” recalls Harris.

Harris got started when he saw a picture of a hang glider in his local paper. “It was an epiphany—a flying machine you could put on top of your car. I couldn’t think about anything else,” he says. Harris ordered a glider, which came with a silent Super-8 film that showed him how to launch and land. With some friends, he took it to Jockey’s Ridge, a giant sand dune on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, and they taught themselves to fly. Soon after, Kitty Hawk Kites—now the largest hang gliding school in the country—was born.

But for all the excitement, there was real danger. “When we started out, we didn’t know a thing about aviation. We just had an overabundance of enthusiasm,” recalls Pagen. Matt Taber, who was one of Harris’s early instructors, has for 40 years run Lookout Mountain, a hang gliding school near the border of Tennessee and Georgia. He recalls an early meet in upstate New York. “I saw a contest at Gunstock ski resort,” he recalls. “And they were landing in trees and chair lifts and all over the place. That had to be like ’74 or ’75.” Bob Wills—the pilot in To Fly!—was the national champion in 1974; his brother Chris had won the year before. They formed Wills Wing as the boom took off. But Bob was killed in 1977 while flying his hang glider in a Jeep commercial. (His younger brother Eric had been killed in a hang gliding accident three years earlier.) That’s when hang gliding took on a reputation for danger it still can’t quite shake.

The sport rapidly matured—glider design and performance improved along with safety procedures and training. Pagen wrote the training manuals that are still used today. “I realized we needed a training curriculum,” says Pagen, “because I had been through the Swiss ski school” and saw parallels. “Both [sports] take place at about the same speeds and require a control of speed. Both can present dangers if certain limits aren’t observed, so both require an awareness of safety. Both require some highly technical and tuned equipment to perform well. So it was natural for me to write a training manual.”

I’ve experienced the first steps of the training process firsthand at both Lookout and Kitty Hawk Kites. At “Kites,” as the instructors call it, the student learns in a Rogallo-wing glider called an Eaglet. “They’re pretty close to what we started with,” says Harris. “They’re so easy to fly and so forgiving. We’ve not been able to improve on that.”

The Kites training method has been boiled down to three words, which are emblazoned on the instructors’ T-shirts: Relax. Look Ahead. Much easier said than done. Students still walk, jog, then run down Jockey’s Ridge, with a tether on the wing held by an instructor running along. As the Wright brothers discovered in 1900, the sand is forgiving—and never far away. Even the clumsiest landing is likely to bruise only an ego.

At Lookout, the student begins on a Wills Wing Alpha, which was designed as a forgiving but higher-performance glider than the Eaglet. There’s no dune. The student runs down steeper, grass covered hills. The “relax look ahead” bit is a little harder to do—terra firma looks a lot more firma on a hill than on a dune. At each school, there are five training flights in the first lesson. It usually takes until the fifth flight not to instinctively pull the downtubes in with a white-knuckle grip (which usually concludes with a face plant). And it’s true—when the glider starts to lift, if you relax and look ahead and just let it lift, you simply fly—slowly, gracefully—and the moment is absolutely magical.

The training for hang glider pilots proceeds through a series of ratings from H(ang)1 to H5. An H1 beginner pilot can launch, fly in a straight line, and land alone. An H5 master pilot has demonstrated over a long period of time the ability to fly a broad range of gliders, conditions, and sites. Pilots are evaluated by certified instructors and a safety committee before they can move on.

The performance of the gliders has improved dramatically. Although the basic layout is similar, there have been many changes in materials, construction, and wing shape. “We use much stiffer spars (leading edges and crossbars), which allows much tighter sails for a more perfect aerodynamic shape,” says Pagen. “Think the wider, narrower wings of a soaring eagle or osprey compared to a non-soaring robin.”

* * *

For all its challenges, hang gliding endures. Its proponents typically cite two things that keep them enthusiastically engaged: the pure experience of birdlike flight and the camaraderie it creates. Klein reveals one of the sport’s unique aspects as her favorite—dune flying. “I really, really love dune flying—flying just five feet off the ground. That’s when I feel most like I’m actually flying,” she says.

But flying alone is also what draws the pilots together, she adds. “Once you step off the mountain, or detach from your tow plane, it’s all up to you.”

In 2018, Weaver convened a gathering of the major stakeholders in the sport to develop a plan for its revitalization. Attracting younger and more diverse participants like Klein is a priority, and the camaraderie she describes might be the key. “The camaraderie is just off the charts. It’s always been very welcoming to me, and I am the oddest duck in the pond,” Mashy says, laughing. “A black woman in hang gliding is a rarity,” she explains. “I’ve been on several different continents, and no one’s ever really seen someone who looks like me, particularly at my level of experience and years in the sport.”

Mashy credits her proximity to Houston for developing a diverse and younger clientele. “Hang gliding should be closer to urban areas,” she says. “Schools should set up near a metropolis. Sonora Wings is near Phoenix. Wind Sports is near L.A. Wallaby is near Orlando. You need to be near somewhere you can draw a variety of people.”

“One of the things I am desperately hopeful that we can start to change in our sport is the percentage of women,” Palmaz says. “It’s a real opportunity to increase the participation and the diversity in gender and in race of the sport, which we need.”

There’s also an effort to make learning hang gliding more accessible. Wills Wing has developed the Easy Flyer, in which the pilot hangs beneath the sail in a seated position. It also has wheels. “It eliminates picking the glider up, holding it at the right angle, running with the glider,” says Harris. “You roll down the hill, and it lifts you off. Sitting is a lot more comfortable for most people. The goal is to make hang gliding as easy as paragliding.”

* * *

At Lookout Mountain, I gathered several young hang gliding instructors (including the tug pilot, my son Tim) around a computer to watch the hang gliding sequence from To Fly! They’re all expert pilots. And yet, when the sequence begins, they get very quiet. When Bob Wills shoots through the crags and points of the volcanic mountain, they erupt. “Holy s---!” Forty-two years later, Bob Wills and To Fly! can blow even these guys away.

Later, I noticed Ellie Bracket, 10 years old, suiting up for a tandem flight—her fourth. She’s had one each year since she was seven. Her mom, a hang glider pilot, was up on the ramp at the top of the mountain getting ready to launch. Her father took pictures as Ellie put on her helmet and harness. What should people know about hang gliding, I asked. “It’s not scary! It’s so peaceful,” she said. What should a kid your age know? “My first flight we buzzed the launch, and there were people with kids watching. It was great to show other kids they could do it too.” Ellie can’t wait to be tall enough to be a hang glider pilot herself.